Summary

This publication is designed to support Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako by bringing together research findings about effective collaboration in education communities. It is supported by the publication Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: working towards collaborative practice. These resources can be used in conjunction with School Evaluation Indicators: effective practice for improvement and learner success (2016) and Effective School Evaluation: How to do and use internal evaluation for improvement (2016).

An additional resource Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Working towards collaborative practice is also available. This separate resource is designed to support CoL | Kāhui Ako as they work towards effective collaborative practice. It is framed around key questions in each of the seven effective practice areas and is able to be used both as evidence-based progressions and as a useful internal evaluation tool.

A third resource, Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako in action is the first of a series of iterative reports which draw together what ERO knows about CoL | Kāhui Ako, as they move from establishment to implementation.

Whole article:

Communities of Learning Kāhui Ako - Collaboration to Improve Learner OutcomesCollaboration to improve learner outcomes

The Government introduced its Investing in Educational Success policy in 2014 with the aim of raising student achievement by promoting effective collaboration between schools and strengthening the alignment of education pathways. The policy provided for new leadership and teaching roles in and across schools and for the deployment of expert partners, both academic and practitioner.

It is expected that up to 250 Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako will be in place by 2017, with the leaders of each community being appointed once establishment is approved. Each community must collectively agree which achievement challenges it will focus on, basing its decisions on an analysis of robust data, and then develop an action plan to address them.

This publication is designed to support Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako by bringing together research findings about effective collaboration in education communities. It is supported by the publication Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: working towards collaborative pratice. These resources can be used in conjunction with School Evaluation Indicators: effective practice for improvement and learner success (2016) and Effective School Evaluation: How to do and use internal evaluation for improvement (2016).

Equity and excellence in student outcomes

The number one challenge facing the New Zealand education system is to achieve equity and excellence in student outcomes.

Our school system is characterised by increasing diversity of students and persistent disparities in achievement. Although many young people achieve at the highest levels in core areas such as reading, mathematics and science, the system serves some students less well.

Young people attending the same school can experience widely divergent opportunities to learn. This within-school inequality is amongst the highest to be found anywhere and is strongly related to achievement disparities.1

The single most important influence on students’ achievement and progress is the effectiveness of the teaching they receive.2 The evidence tells us that some teaching practices are much more likely to promote learning than others, and that teacher experience does not necessarily equate to teacher expertise.

One way of addressing this variability is to focus the system on collaborative expertise and student progression.3 In collaborative cultures, all members of the community share responsibility for the success of students. Teachers are given the necessary support, time and resources to collaboratively diagnose students’ learning needs (and their own, too) and to plan and evaluate teaching programmes and strategies.

The Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako initiative provides an important opportunity to build knowledge and expertise, stimulate improvement and innovation,4 and improve teaching and learning through collaboration.

Evaluation for equity and excellence

Evaluation is the engine that drives improvement and innovation. Effective evaluation is critical in achieving equity and excellence in student outcomes.

Evaluation is a form of disciplined inquiry concerned with the determination of value.5

Evaluation involves making a judgement about the quality, effectiveness or value of a policy, programme or practice in terms of its contribution to the desired outcomes. The evaluation process involves systematic consideration of the questions: What is so? Why is it so? So what? Now what? 6

In a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako, using evaluation for improvement will facilitate collaborative action through enabling the community to better understand:

- how individual learners and groups of learners are performing in relation to valued outcomes

- how improvement actions taken have impacted on learner outcomes and what difference is being made

- what needs to be changed and what further action needs to be taken

- the patterns and trends in outcomes over time

- what kinds of practices are likely to make the most difference for learners and in what contexts

- the extent to which the improvements being achieved are good enough in terms of the community’s collective vision and priority goals and targets.7

Evaluation and organisational learning are closely linked.8 The quality of evaluation leadership and collective depth of evaluative knowledge and expertise will determine the extent to which a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako can collaboratively carry out and use evaluation for improvement. Doing and using evaluation effectively requires asking good questions, gathering fit-for-purpose data and information, making sense of, and thinking deeply about that data and information in order to develop the understanding that enables good decision-making.9

Evaluation methods and evaluative thinking provide the tools for systematically gathering and interpreting evidence that can be used to provide information about progress and provide feedback loops for refinement, adjustment, abandonment, extension and new learning.10

Building the capacity of a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako to engage in strong evaluative reasoning and evaluation processes is critical in enabling the community to achieve its collective vision and priority goals and targets for equity and excellence.

Contributing to the collaborative endeavour

For a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako to develop and function effectively the participants need to shift both their thinking and practice. For some, the biggest challenge is to enlarge the focus to include not only the students in their own school but also the students in all the other schools. Being part of a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako means accepting a collective responsibility for equity and excellence across all the schools in the community.

Collective responsibility positions leadership differently. Leading improvement across a range of diverse contexts can require different expertise and different ways of working. Members of a community need to be clear about the purpose of leadership roles and the responsibilities they entail. Effective leadership is vital if the joint work that goes into a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako is to contribute to collective outcomes.

Equitable allocation of resources, especially time and expertise, is essential for enabling a community to function in ways that grow capability and capacity.

To contribute to and benefit from a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako, each participating organisation needs to be able to provide a robust analysis and interpretation of their outcomes data along with priorities for improvement. Openness to learning and a willingness to share information and evidence are important conditions for collaborative inquiry that leads to improved professional practice and enhanced student outcomes.

Building collective capacity for improvement

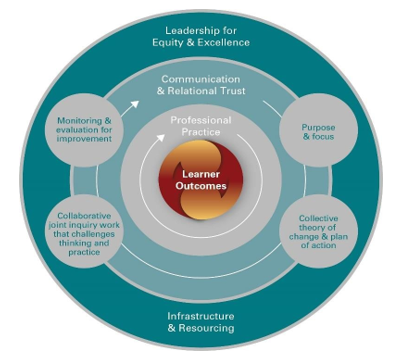

The framework below identifies what the evidence suggests is important in the development of collective capacity for improvement. This framework is a starting point for further developing the New Zealand evidence base. The sections that follow describe the components of the framework and include examples of effective practice.

This image is of increasing circles with Learner Outcomes at the centre. The next circle outwards is called Professional Practice with an arrow tracing its way around the circle. The next circle is called Communication and Relational trust. This also has the arrow tracing its way around the circle but it has four circles placed at intervals on the arrow. They are from right top, Purpose and focus, Collective theory of change and plan of action, Collaborative joint inquiry work that challenges thinking and practice and Monitoring and evaluation for improvement. The last circle which encompass all other circles is titled Leadership for Equity and Excellence.

Leadership for equity and excellence

Effective leadership is a defining characteristic of Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako that make a difference for students. Leaders have a crucial role to play in the development of a compelling collective vision and priority goals and targets that represent the perspectives and aspirations of the community, especially the students, parents and whānau.

Effective community leaders ensure that resources are used to create the conditions that enable members to work together to pursue the agreed goals. By accessing appropriate professional expertise, both internal and external, they are able to focus inquiry and actions on practices that are most effective in improving provision, pathways and outcomes. They put in place systems, processes and ongoing monitoring and evaluation that make it possible to track progress, determine the impact of actions, and make adjustments in response to challenges encountered.

Providing opportunities for leadership, whether in specific contexts or for specific tasks,11 helps embed collaborative ways of working. Leaders in these positions model effective practice, facilitate learning and leadership in others, support collective investigation of new possibilities, make changes, and sustain improvement.12

By facilitating collaboration, effective leaders build relational trust at every level of the community.13

Examples of effective practice

- Community leadership focuses on achieving equity and excellence in student outcomes in every participating institution.

- Members have a shared understanding of the roles and responsibilities of those with leadership positions in the community.

- Leadership collaboratively develops and pursues the community’s vision, goals and targets.

- Leadership seeks the perspectives and aspirations of students, parents and whānau, and incorporates them in the community’s vision, goals and targets.

- Leadership knows the groups within the community well and takes responsibility for their development, creating opportunities for collaboration and strengthening the conditions that enable improvement.

- Leadership is flexible and responsive, shared across a range of leaders whose authority is derived from their expertise.

- Leaders have expertise in focused instructional leadership, demonstrating exemplary teaching and learning practice, understanding and sharing appropriate theory and research, and guiding reflection and inquiry.

- Leadership coordinates and supports effective collaboration, building relational trust at every level of the community.

- Leadership ensures that organisational structures, processes and practices support collaboration and professional learning that is focused on improving student outcomes.

- With the support of external expertise as required, leadership identifies and develops the internal expertise necessary for ensuring that improvement goals are met.

- Leadership builds collective capacity to do and use evaluation and inquiry for sustained improvement.

- Leadership monitors and evaluates the impact of actions on practice and student outcomes and makes changes as necessary.

Communication and relational trust

Effective communication and high levels of relational trust create the conditions for successful organisational learning and change.14 Developing relational trust goes hand in hand with collaboration, and both take time. In the early days of a community, leadership should provide formal and informal opportunities at different levels for purposeful, joint work with a shared focus.

Relational trust is a prerequisite for engaging in challenging conversations15 and for creating an environment where participants are open to their practice and the outcomes they achieve for students being made transparent.16 Where there is relational trust, members feel free to open up and acknowledge what they do not know, take risks, and use their knowledge and expertise to support others in the community. Trust relationships facilitate the sharing of data and information about students and the provision of supported educational pathways.

When parents, families and whānau are actively engaged in the Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako enterprise, the community gains access to community resources, and educational pathways and outcomes are enhanced.

In any Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako the quality of leadership and relationships will be evident in the way in which high-performing schools work with other schools to improve overall performance and outcomes.17

Examples of effective practice

- Trust-based relationships foster connectedness and collective purpose among the members of the Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako.

- Well-developed communication channels facilitate the exchange of ideas and synthesis and use of new knowledge.

- Transparent sharing of data enables community members to learn from others, improve their practice, and raise student outcomes.

- Community members confidently acknowledge what they don’t know, engage in challenging, open-to-learning conversations, and feel supported to take risks.

- Strong, educationally focused relationships among students, parents and whānau, teachers and leaders, and with other educational and community institutions, increase opportunities for student learning and success.

Purpose and focus

High performing Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako are characterised by their clear purpose and focus. The starting point for this clarity is effective internal evaluation at both the individual member and community levels. Analysis of student achievement data and investigation of practice leads to the identification of issues that provide a basis for shared purpose and direction.

… a common goal has to be at the same time inspiring and measurable … goals without a link to outcomes are meaningless. There must be a shared commitment to ‘know thy impact’.18

Ongoing use of transparent, timely data and information on student and institutional performance enhances collaboration by enabling participants to evaluate progress and the effectiveness of the actions they have taken. Impact that can be clearly demonstrated through measurement builds collective efficacy and ownership and promotes further improvement efforts.

Examples of effective practice

- The community has a small number of high-leverage, ambitious and measurable learning goals for students, teachers and leaders that are clearly articulated and understood.

- The community has a shared focus on enabling positive educational pathways for students.

Collective theory of change and plan of action

The process of clarifying purpose and focus provides a foundation for further investigation and collaborative sense making that leads to priorities for action.

Identifying achievement challenges may be relatively easy; understanding them and how to address them is likely to take some investigation. At this point the community needs to research the evidence about ‘what works’ and what ‘good’ looks like with a view to determining possible actions based on their demonstrated effectiveness.

Planning effectively will mean that the community:

- is clear about which students it needs to focus on to ensure equity and excellence of outcomes

- understands what aspects of practice need to improve and how they might be improved

- considers and selects options in light of the evidence about what will make the most difference

- knows where the capability and capacity to improve lies and identifies what external expertise is needed

- identifies what actions should be taken, and why, and what success looks like

- allocates resources to support the chosen actions.

Leadership ensures that the structures, processes and resources to support the implementation of the community’s planned actions are in place.

Examples of effective practice

- The community’s action plan reflects an integrated theory of improvement: problem definition, rationale for and alignment of solutions, targets and success indicators, monitoring and evaluation.

- The community has identified and selected improvement actions based on evidence about their likely effectiveness.

- The community has identified, put in place and communicated structures and practices that will enable shared ways of working.

- Sufficient resources are allocated to support the goals and actions.

- All members of the community are engaged in and show ownership of the plan to address the identified achievement challenges.

Collaborative inquiry and working that challenges thinking and practice

In a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako, the focus of collaboration is on improving outcomes for students through changes in instructional practice. Collaboration involves working together on shared challenges that have been identified through the use of evidence.

Effective collaboration engages participants in ongoing cycles of inquiry:

- identifying what is going on for students in relation to valued outcomes

- using credible evidence, identifying a problem of practice that will stretch existing knowledge and capacity but also be manageable

- designing, trying out and testing changes in practice that are aimed at solving the identified problem

- accumulating evidence of impact, refining or discarding ideas based on evidence of their effectiveness, embedding changes that prove to be effective into daily practice

- identifying the next student-related challenge.19

Effective collaboration is characterised by dense, frequent sharing of knowledge among participants, with the aim of addressing the identified challenges. Members of highly effective groups interact frequently among themselves, focusing on refining and consolidating professional practice. They also connect outwards, to gain new knowledge that will complement what they already know and to maintain connections with, and actively participate in, larger networks.20

Educators experience increased efficacy and agency when leaders provide opportunities and support for engaging in collaborative inquiry and when they ensure that participants at all levels have a voice in how inquiry processes are set up and work.21

Examples of effective practice

- Community members have a clear, shared vision and purpose and a compelling agenda for change.

- Leaders and teachers are data literate: asking focused questions, using relevant data, clarifying purposes, recognising sound evidence, developing understanding of statistical concepts, engaging in thoughtful interpretation and evidence-informed conversations.22

- Appropriate tools and methods are used to gather, store and retrieve a range of valid data.

- The community engages in cycles of collaborative inquiry for the purpose of improving instructional practice.

- Researchers and practitioners work together to identify problems of practice and performance measures and to design, test and refine improvement actions.

- Participants engage in focused interaction and dense, frequent knowledge sharing that contributes to the consolidating and refining of practice.

- The community connects outwards to access new ideas and the expertise needed to support improvement and innovation.

- Timely access to appropriate expertise builds capability for ongoing improvement and innovation.

- Community collaboration enriches opportunities for students to become confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners.

Monitoring and evaluation for improvement

The members of effective communities are clear about what they want to achieve and how they will recognise progress. This means they can recognise what is and is not working, and for whom, and can adjust their actions or strategies accordingly. They have access to evaluation leadership and are developing data literacy and technical evaluation expertise. They use appropriate tools and methods.

Effective communities have systems, processes and tools in place to generate timely information about progress towards goals and the impact of actions taken. This infrastructure supports data gathering, sense making, decision making and knowledge building.23

As in effective schools, evaluation, inquiry and knowledge building processes are purposeful and coherent, enabling the generation of new knowledge and ensuring that it is used at every level and across the community to promote improvement. These processes increase accountability for learner outcomes and strengthen professional capital.24

Examples of effective practice25

- Members of the community own the change process and seek evidence of impact.

- The community uses a range of evidence from evaluation, inquiry and knowledge building activities for the purposes of selecting, developing and reviewing strategies for improvement.

- Low-performing schools in the community improve their performance.

- Collaboration and involvement in decision making enhance the self- efficacy and collective resolve of leaders and teachers to drive improvement across the community.

- The community is characterised by strong group norms and behaviours and a strong sense of responsibility for outcomes (internal accountability).

Sufficiency of resourcing and supportive infrastructure

Coordination of resources and the provision of a supportive infrastructure are critical leadership responsibilities in a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako. While the operational activities of communities need appropriate resourcing, the resources that matter most are those that create the conditions for effective collaboration. Above all, collaboration needs to be resourced with time.

It takes expert leadership and facilitation skills to develop trust relationships in a group of self-managing organisations that have not previously worked together. This trust needs to be built at different levels and across the community.

Those appointed to leadership roles in a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako are themselves a resource to be used effectively. It is important therefore that members have a clear understanding of the responsibilities involved, and that shared ways of working are quickly developed.

It may also be necessary to establish new data management systems to support ongoing, transparent sharing and use of data in ways that facilitate effective collaborative inquiry.

In effective communities, high-performing schools work constructively with low-performing schools to improve performance.26 These improvement efforts need to be supported by equitable allocation of resources.

Ultimately, it is by strengthening the resource that resides in the people and leadership of a community that a foundation is laid for ongoing improvement and sustainability. Allocation of resources is clearly aligned to the community’s vision, goals and targets.

Examples of effective practice

- Adequate provision is made for joint planning, collaborative inquiry and professional learning within member institutions and across the community.

- User-friendly data management systems provide timely, relevant, transparent data that enables tracking of student achievement and progress in and across community institutions.

- Infrastructure and organisation enable effective coordination and engagement of community members in purposeful, joint work.

- Community meetings maximise the time spent inquiring into teaching practice and its impact on outcomes, using evidence of student learning.

- Community members who are in change-agent and facilitation roles have access to effective leadership and capability development opportunities.

- Leadership creates pathways across social boundaries to facilitate the movement and use of knowledge and ideas within the community.27

Improving learner outcomes

The research on the power of collaborative cultures to get results has been accumulating over 40 years. It points to the power of social capital – the agency and impact of strong and effective groups – to improve student learning.28

In the context of the Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako initiative, the primary purpose of collaboration is to improve student outcomes. To achieve equitable outcomes for those who have been under-served by the system, particularly Māori and Pacific students, this means an unyielding focus on accelerating achievement. To support this endeavour, we now have a wealth of evidence about how to most effectively promote equity and excellence for diverse learners.

The New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa set the direction for learning in our schools. These two curriculum frameworks are supported by national achievement standards and by other key policy documents such as Ka Hikitia, the Pasifika Education Plan and Success for All – Every School, Every Child. Collectively, these documents describe the outcomes we want for all learners.

The New Zealand Curriculum encapsulates these outcomes in its vision of young people who are ‘confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners’. The success of the Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako initiative will be apparent in the extent to which every young person who is part of a community is:

- confident in their identity, language and culture as a citizen of Aotearoa New Zealand29

- socially and emotionally competent, resilient and optimistic about the future30

- a successful lifelong learner

- participating and contributing confidently in a range of contexts (cultural, local, national and global) to shape a sustainable world of the future.31

Citations

1 Schmidt, W., Burroughs, N., Ziodo, P., & Houang, R. (2015). The role of schooling in perpetuating educational inequality: an international perspective. Educational Researcher, 44 (7), 371–386.

2 Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

3 Hattie, J. (2015). What works best in education: The politics of collaborative expertise. London: Pearson.

4 Ainscow, M. (2015). Towards self-improving school systems. New York: Routledge.

5 Cronbach, l., & Suppes, P. (1969) cited in Schwandt, T. (2015). Evaluation foundations revisited: Cultivating a life of the mind for practice. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

6 Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilisation-focused evaluation. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

7 Education Review Office (2016). Effective school evaluation: How to do and use evaluation for improvement. Wellington.

8 Cousins, B., Goh, S., Elliott, C., & Bourgeois, I. (2014). Framing the capacity to do and use evaluation. In Cousins,

J.B. & Bourgeois, I. (Eds.). Organisational capacity to do and use evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 4, 7-23.

9 Earl, L. (2014). Effective school review: considerations in the framing, definition, identification and selection of indicators of education quality and their potential use in evaluation in the school setting. Background paper prepared for the Education Review Office’s Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews.

10 Earl, L., & Timperley, H. (2015). Evaluative thinking for successful educational innovation. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 122, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrxtk1jtdwf-en

11 Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R.D., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). A theoretical and empirical investigation of teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools. Teachers College Record, 109 (4), 877–896.

12 Ainscow, M. (2015). Towards self-improving school systems. New York: Routledge.

13 Bryk, A., Sebring, P., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. (2010). Organising schools for improvement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

14 Bryk, A., Sebring, P., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. (2010). Organising schools for improvement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bryk et al. identify a reciprocal dynamic between trust development and school improvement, including teachers’ work orientation, the school’s engagement with parents and the sense of safety and order experienced by students.

15 Timperley, H. (2015). Professional conversations and improvement-focused feedback. A review of the research literature and the impact on practice and student outcomes. Melbourne VIC: Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

16 Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Fullan, M. (2015). The social physics of educational change: Essential features of collaboration. Draft for comment prepared for the Ministry of Education.

17 Chapman, C., & Muijs, D. (2014). Does school-to-school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. School Effectiveness and Improvement, 25 (3), 351–393.

18 Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Fullan, M. (2015). The social physics of educational change: Essential features of collaboration. Draft for comment prepared for the Ministry of Education.

19 Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Fullan, M. (2015). The social physics of educational change: Essential features of collaboration. Draft for comment prepared for the Ministry of Education.

20 Chapman, C., & Muijs, D. (2014). Does school-to-school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. School Effectiveness and Improvement, 25 (3), 351–393.

21 Butler, D., Schnellert, L., & MacNeil, K. (2015). Collaborative inquiry and distributed agency in educational change: A case study of a multi-level community of inquiry. Journal of Educational Change 16, 1–26.

22 Earl, L., & Timperley, H. (2009). Understanding how evidence and learning conversations work. In L. Earl & H. Timperley (Eds), Professional learning conversations: Challenges in using evidence for improvement. Cambridge: Springer.

23 Education Review Office & Ministry of Education (2016). Effective School Evaluation: How to do and use internal evaluation for improvement. Wellington.

24 Fullan, M., Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Hargreaves, A. (2015). Professional capital as accountability. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23 (15), 1–22.

25 See also Education Review Office (2016). School Evaluation Indicators. Wellington: Author. Domain 6: Evaluation, inquiry and knowledge building for improvement and innovation.

26 Chapman, C., & Muijs, D. (2014). Does school-to-school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. School Effectiveness and Improvement, 25 (3), 351–393.

27 Ainscow, M. (2015). Towards self-improving school systems. New York: Routledge.

28 Fullan. M., Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Hargreaves, A. (2015). Professional capital as accountability. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23 (15), 1–22.

29 Te Marautanga o Aotearoa Graduate Profile.

30 Education Review Office (2013). Wellbeing For Success: Draft Evaluation Indicators for Student Wellbeing and The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) Health and Physical Education.

31 Bolstad, R., & Gilbert, J., with McDowall, S., Bull, A., Boyd, S., & Hipkins, R. (2012). Supporting future-oriented teaching and learning – a New Zealand perspective. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from www.educationcounts.govt.nz