- Audience:

- Academics

- Early learning

- Education

- Māori-medium

- Parents

- Schools

Insights from Nicholas Pole, Te Tumu Whakarae mō te Arotake Mātauranga | Chief Executive and Chief Review Officer

In this issue of ERO Insights we cover a range of topics relevant to the daily challenges faced by schools and early childhood education centres. We:

- update you on how we are involving the sector in the detailed design and implementation of our new operating model for school reviews

- provide insights into how aggregated information from ERO’s school reviews can inform our understanding of education system performance

- share our latest research on how schools and ECE providers are coping with the impacts of Covid-19

- review research on ways to combat the growing problem of student absenteeism, and

- look at how schools are teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi.

ERO’s latest work on the impacts of Covid-19 research is particularly relevant given the current Level 3 restrictions in Auckland and Level 2 elsewhere. It found that, despite the challenges, two-thirds of schools said they had successfully prepared for the first lockdown. Anecdotally we are also hearing that schools and early learning services are applying what they learnt to the current restrictions.

ERO is taking the learnings from this research into account when planning its own work, now that most of the country is operating at Alert Level 2. At level 2 we are continuing to do reviews but are looking at how we can reduce our time on site and the burden on participants. As always, if you are due for a review, we will talk to you first and will take your particular circumstances into account.

In other news, we introduce Jane Lee, ERO’s new Deputy Chief Executive – Review and Improvement Services. Jane replaces Di Anderson, who will be well known to many of you from her lifetime commitment to education – the last 30 years of which were in various roles in ERO. She has made a huge contribution to New Zealand education in that time and will be missed. Hers are big shoes to fill, but I’m confident Jane is a worthy successor.

ERO Insights – as the name suggests – is about providing useful insights into areas that make a difference for our tamariki and rangatahi. We hope you find it useful and we always welcome feedback.

- Working with the sector to refine the new model for school reviews

- Gaining a deeper understanding of the impacts of Covid-19

- Varied interventions needed to combat increasing student absences

- Teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi – what are schools doing?

- School Evaluation Indicators: How they help us understand the education system

- Leadership Partners pilot programme enables meaningful exchanges

- Meet the Team: Jane Lee

- Discontinuation of ERO’s audits for the Teaching Council

Working with the sector to refine the new model for school reviews

In the first half of this year ERO has explored a new approach to school evaluation and how we can work best with schools to support continuous improvement.

This work is in response to the Government’s reform of the Tomorrow’s Schools system, Supporting all schools to succeed, which was released in November 2019. The Government asked ERO to strengthen the capability of schools to undertake self-evaluation and continuous improvement, and to work towards ensuring effective engagement with whānau and community. The goal is to better target ERO resources towards schools who have a greater need and towards system-level evaluation.

We have taken on board feedback from the Tomorrow’s Schools review taskforce about what wasn’t working, as well as input from sector groups and principals which has helped us to understand what people want from ERO.

The result is a draft model which envisions ERO working alongside schools to co-construct a plan for evaluation that takes account of the culture and context of their community and school environment, and identifies areas of strengths and particular need.

We are moving into the implementation phase of the model and will engage a cross-section of schools around the country to take part in a prototype development process to help us refine our approach further and ensure it is working for both schools and ERO, as well as delivering on the expectations of the Government. We expect to start introducing the model more widely from early 2021.

This work represents a significant shift in the way ERO will work with schools, and an opportunity to make our evaluation process fit for purpose. As we continue to develop our approach, we will continue to update you on our progress and provide more information about when you can expect to hear from us about your school’s involvement.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the impacts of Covid-19

ERO continues to investigate the impacts of Covid-19 on schools and early learning centres and to quickly share its findings to help you prepare and respond to the ongoing challenges from Covid-19.

Covid-19: Impact on Schools and Early Childhood Services interim report provides our initial analysis from the second round of this research. It is based on interviews with 110 schools and 95 early learning services in the English medium education sector in June, July and August 2020 and insights from the Māori medium education sector. Our interviews with schools, leaders and services focused on:

- What helped in lockdown?

- How well have children/students transitioned between lockdown levels?

- What are the ongoing challenges?

The key findings include:

In early years…

- Gradual reopening helped – nearly half of the services reported this

- Anxiety is an issue – one-in-three services reported anxiety of parents and kaiako

- Kaiako stress and sick leave is an issue – one-in-five services report staff absences and one-in-ten services indicated that next time they would “focus on staff wellbeing” earlier

- Attendance is holding up for now – less than a fifth of services reported reduced rolls or children attending fewer hours (but this may change when the wage subsidy ends)

- Vulnerable children may be struggling – some services reported concern that children with additional learning needs have not progressed as expected.

In schools…

- Staff wellbeing is the biggest concern – three-quarters of schools reported challenges related to exhaustion, sickness, stress about workload, anxiety about health, or principal stress

- Learner wellbeing has been the priority – nearly three-quarters of schools reported prioritizing learner wellbeing over academic learning during lockdown. Many reported deferring planned assessments

- Lower-decile schools are facing more challenges transitioning students back to school

- A quarter of schools reported financial concerns.

What helped in early childhood services?

Looking at what helped for early childhood services in lockdown, three themes emerged:

- Regular and clear communication. Regular and clear communication with kaiako, parents and whānau has been a key priority for all services – 80% reported that they had contacted parents and whānau over the lockdown period.

- Supporting parents. Nearly half of services reported that their kaiako had encouraged and supported parents to help their children learn at home. A fifth of services provided online curriculum experiences, which included literacy, music and dance. Other support provided by services included providing information related to children’s behaviour and support for families who are struggling financially. Over a third of services provided Ministry of Education (MoE) resource packs to children. In addition, a third of kindergartens and home-based education and care services said they provided their own resource packs.

- Support from MoE. Two-thirds of services reported that the MoE Bulletin provided “very useful and succinct information”. Nearly a third of services (30%) commented on the supportive telephone calls and guidance provided by the Ministry’s regional offices.

What helped in schools?

For schools there were four themes identified as helping during lockdown:

- Being prepared. Two-thirds of the schools reported that they had successfully prepared for lockdown. Factors associated with schools who reported being prepared included using digital technology as an established part of their teaching practice and having up-to-date contact details for learners and whānau. Some of these schools reported that they had been planning and preparing in advance of any official guidance, based on their own monitoring of the pandemic, nationally and internationally.

- Support from MoE and others. Nearly half of leaders expressed positive feedback about MoE’s communications and bulletins, while noting that it was often difficult to keep up with the quantity of guidance, and the pace of change as the situation developed. The distribution of digital devices was challenging, but leaders were positive about MoE’s physical learning packs. Some leaders also reported that they had been well supported by their Kāhui Ako or other regional networks or professional networks. Board chairs were very positive about the advice and guidance they received from the New Zealand School Trustees Association.

- Strong communications. Many leaders reported that this regular communication helped to build teacher relationships with whānau and gave whānau greater insight into their children’s learning. Teachers used a combination of phone calls, emails, video calling and other digital platforms to regularly check in with learners and whānau. This was key to maintaining learner engagement, and as a way of monitoring learner and whānau wellbeing. Around a third of leaders specifically cited greater whānau involvement and integration of home and school learning as a success over the period. In the Māori medium education sector, leaders strengthened their communication with their kura whānau, which had a profound calming and reassuring impact on whānau, kaiako and the wider community.

- Prioritising wellbeing. Seventy percent of leaders reported that they had explicitly prioritised learner wellbeing over academic learning during lockdown. Leaders recognised that they could not expect the normal level of engagement and workload during lockdown and made clear to learners and whānau that learning was second to wellbeing. Some schools reported modifying their curriculum to include more fun activities, and to encourage learners to engage in physical activity as appropriate. Wellbeing was also the main priority for leaders across the Māori medium education sector, which included the health, safety, physical needs (emotional, cultural and spiritual) of whānau and kaiako.

These findings are preliminary but are being shared early to help the sector to understand and plan for the ongoing impacts of Covid-19.

ERO’s future work in this space will include a follow-up survey of principals, teachers and students to understand ongoing impacts; analysis of selected schools to investigate the ongoing impact on student engagement and achievement; and targeted focus groups to learn more about a range of issues, including how to ensure preparedness of schools for future lockdowns and impacts on Māori and Pacific student outcomes.

ERO’s first report, Covid-19: Learning in Lockdown, surveyed teachers and students about their experience of teaching and learning in the initial lockdown.

Varied interventions needed to combat increasing student absences

Regular attendance is declining1

Over the last five years, and prior to entering this unsettled COVID-19 period, there has been a dramatic decline in the number of students attending school regularly. The Ministry of Education defines regular attendance as being present at school for 90 percent or more of the year. However, even if a student attends 90 percent of the time, they will have missed the equivalent of an entire year of schooling by age 16. In 2015, 69 percent of students attended regularly; by 2019, this number had fallen to just over 58 percent. Even for those students who do attend regularly, they are attending fewer days than they did last year. The Ministry has examined the relationship between attendance and NCEA credit attainment, suggesting that there is no ‘safe’ level where academic results are unaffected by absences. Therefore, it is important to look at attendance even among those students within the ‘regular’ attendance bracket, particularly since we are seeing a downward trend. This is backed up in international literature, which links absenteeism with areas such as wellbeing and social development, as well as academic success.2 This article summarises the recent evidence about the decline in regular attendance in New Zealand schools, provides a short review of what may contribute to absenteeism, and a discussion about what schools could do to improve attendance.

Absences increased across all schools and all students

The decline in regular attendance has occurred across all categories of schools and students. As such, we cannot afford to focus solely on a single group. That said, students in primary school, and those students who identify with a Māori or Pacific ethnicity, have seen a more pronounced decline in regular attendance. Among all students, full-day absences were most common, half-day absences were less common, and individual lesson absences were least common. These absences were most likely to be on Mondays or Fridays. However, there has also been an increase in students missing at least two days in a row, most commonly on both Thursday and Friday.

Increase in students not attending due to illness

Over half of the recorded absences were considered ‘justified’. These justified absences had been fluctuating until 2019 saw a spike in numbers. The most common recorded reason for a justified absence was sickness, though the Ministry suggests that this cannot easily be explained away by a harsh flu season. Unjustified absences have steadily increased since 2015 and are most often categorised as ‘unexplained’. As more investigation has gone into the causes of absences, it has become clear that the difference between unjustified and justified absences is less distinct than traditionally assumed. Investigating absenteeism for any reason – whether justified or unjustified – is important, as any absence means the student is not at school and is missing the benefits of attending school. Moreover, poor attendance now often predicts poor attendance later: students with poor attendance at a young age tend to attend less throughout their school life, if no action is taken.

Why might students not be attending regularly?

The decision to miss school is often complex. It is generally understood to be an interaction of multiple factors, with schools, students, parents and whānau each forming a pillar that should support attendance. School factors that may influence a decision to not attend include bullying, an unsafe environment, poor teacher-student relationships, or a lack of engaging or culturally responsive curriculum. Parent/whānau factors may include parentally condoned absences (for example, allowing their student to avoid physical education), family relocation, family holidays, low value placed on education, or an adverse home environment, including precarious housing circumstances. Student factors may include avoidance coping (for example, avoiding class because they haven’t done their homework), mental health needs, peer relationships, a lack of engagement, or boredom.3 The Behavioural Insights Team have undertaken some work in New Zealand, publishing a report that focuses on unjustified absences. They identified two broad explanations for unjustified absences in secondary schools. Firstly, family disengagement, possibly due to distrust of the school, shift work leading to limited oversight, or drug and alcohol problems. Secondly, student disengagement, possibly due to mental health issues, or uninterest in the content of classes. Overseas, case studies have also frequently identified bullying as a key driver of non-attendance.4 Given recent ERO and OECD reports highlighting the prevalence of bullying in New Zealand schools, it seems an important factor to consider.

How do we approach a solution?

Strategies to address attendance may differ across age groups, as the causes for absenteeism may be different. Younger students generally tend to have less agency in the decision not to attend school compared with older students, that is, parents are generally more involved in the decision process for younger students. Parents could also be making it easier for students to skip a day of school by providing a justifiable reason to the school, such as sickness. This does not necessarily mean parents are at fault; rather it recognises that attendance interventions should seek to influence and engage parents in some way, especially for younger students. One promising intervention focused on engaging parents that has been tested in the United States served to promote and reinforce the importance of attendance to parents through tailored text messages.5 The trial looked at those in the early years of primary (equivalent) schools, and focused on reducing the number of students that were absent for 10 percent or more of the time. It sought to diagnose barriers to attendance, such as transport or work circumstances. Part of the service also aimed to make caregivers aware of services and resources that were in place to support them, particularly in getting to school. They found that the pilot schools had a substantially lower absence rate compared to previous years, and 10 percent lower absence rate than the ‘average’ school in the intervention year.

With complex and interacting causes, absenteeism is unlikely to be resolved by a single approach and requires intervention at many levels. One attempt to pool this information is Attendance Works, an initiative in the United States. There are resources for schools to facilitate thinking around attendance, which may also have some value for us in New Zealand. Attendance Works utilises a model developed by Kearney and Graczyk (2014), who suggest interventions to promote attendance and reduce absenteeism could be tiered to help match the problem with a possible solution. Table 1 below lays out each of the three tiers suggested, along with which students the intervention seeks to support. It is important to note that while the decline in regular attendance calls for targeted approaches in this model, it also suggests that universal interventions could have a strong preventative role. Among the universal approaches, monitoring and following up on absences is essential, as this underpins all other interventions and is vital in determining what actions to take next.

Table 1: Three tiers of interventions

|

Who is this for? |

What types of interventions? |

|

|

Tier 1: Universal interventions |

All students, all the time |

Monitoring and following-up on absences. School climate interventions. Safety-oriented strategies, such as supporting student advocacy groups. School-based mental health programmes. Parental involvement initiatives. Learning support strategies, such as providing home-learning material. |

|

Tier 2: Targeted interventions |

Students with declining attendance |

Providing specific and relevant feedback to parents/whānau, such as feeding back about content students miss during absences Improving student engagement, such as developing culturally responsive curricula Teacher or peer mentoring, such as older students assisting in understanding and managing expectations Mental health and wellbeing support, such as counselling |

|

Tier 3: Intensive interventions |

Students who are chronically absent |

Parent/whānau involvement strategies Alternative educational programmes and schools Intensive case management |

The key points to note from this article are:

- Attending school is important and worthwhile.

- Absenteeism is increasing, even amongst students who attend school regularly.

- The cumulative effect of absences is significant. Those attending 90 percent of the time effectively lose a year of schooling by the time they are 16.

- Each absence has an effect; there is no ‘safe’ number of days to miss school.

- All absences should be monitored and followed-up on, including both justified and unjustified.

- The reasons that students miss school are varied, complex, and often interdependent.

- There is no ‘silver bullet’ for improving attendance, and compliance is only one of many interventions schools could use.

With the ongoing implications of Covid-19 on schooling, attendance and engagement become even more important conversations. Understandably, Alert Level 3 and 4 states have created a significant disruption to normal schooling, and a heightened risk of disengagement for some learners. Some of the factors that we have identified as contributing to absenteeism have undoubtedly been exacerbated; striking a balance between highlighting the value of being in school and accommodating the difficult circumstances around the pandemic is challenging but critical.

Works Cited

Ministry of Education | Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga (February 2020) “Student Attendance Survey Term 2, 2019”. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2503/new-zealand-schools-attendance-survey-term-2,-2019

Behavioural Insights Team (August 2018) “Using behavioural insights to reduce unjustified school absences” Ministry of Education | Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/schooling/using-behavioural-insights-to-reduce-unjustified-school-absences

Childs, Joshua, and Ain A. Grooms (2018) “Improving School Attendance through Collaboration: A Catalyst for Community Involvement and Change.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) pp. 1-17. DOI:10.1080/10824669.2018.1439751.

Education Review Office| Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga (May 2019) “Bullying Prevention and Response: Student Voice May 2019”. https://ero.govt.nz/publications/bullying-prevention-and-response-student-voice-may-2019/

Gottfried, Michael (ed), and Ethan Hutt (ed) (2019) Absent from school: understanding and addressing student absenteeism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Education Press.

Gottfried, Michael A, (2010) “Evaluating the Relationship Between Student Attendance and Achievement in Urban Elementary and Middle Schools: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” American Educational Research Journal Vol. 47: pp. 434-465. DOI:10.3102/0002831209350494.

Gren-Landell, Malin, Cornelia Ekerfelt Allvin, Maria Bradley, Maria Andersson, and Gerhard Andersson (2015) “Teachers’ views on risk factors for problematic school absenteeism in Swedish primary school students.” Educational Psychology in Practice Vol. 31, No. 4: pp. 412-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1086726

Havik, Trude, Edvin Bru, and Sigrun K. Ertesvåg (2014) “Assessing Reasons for School Non-attendance.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research pp. 1-21. DOI:10.1080/00313831.2014.904424.

Kearney, Christopher A., and Patricia Graczyk (2014) “A Response to Intervention Model to Promote School Attendance and Decrease School Absenteeism.” Child Youth Care Forum pp. 1-25. DOI:10.1007/s10566-013-9222-1.

Kearney, Christopher A., Carolina Gonzálvez, Patricia Graczyk, and Mirae J. Fornander (October 2019) “Reconciling Contemporary Approaches to School Attendance and School Absenteeism: Toward Promotion and Nimble Response, Global Policy Review and Implementation, and Future Adaptability (Part 1).” Frontiers in Psychology. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02222.

Keppens, Gil, and Bram Spruyt (2017) “Towards a typology of occasional truancy: an operationalisation study of occasional truancy in secondary education in Flanders.” Research Papers in Education Vol. 32: pp. 121-135. DOI:10.1080/02671522.2015.1136833.

Malcom, Heather, Valerie Wilson, Julia Davidson, and Susan Kirk (May 2003) Absence from School: A study of its causes and effects in seven LEAs. Research Report, University of Glasgow, Nottingham: Department for Education and Skills

OECD (2019) “PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives.” PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

Reid, Ken (November 2008) “The causes of non-attendance: an empirical study.” Educational Review Vol. 60, No. 4: pp. 345-357.

Smythe-Leistico, Kenneth, and Lindsay C. Page (2018) “Connect-Text: Leveraging Text-Message Communication to Mitigate Chronic Absenteeism and Improve Parental Engagement in the Earliest Years of Schooling.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) pp. 1-14. DOI:10.1080/10824669.2018.1434658.

1 This articles refers to data prior to the interruption to our system resulting from the advent of Covid-19

2 Michael A. Gottfried, (2010) “Evaluating the Relationship Between Student Attendance and Achievement in Urban Elementary and Middle Schools: An Instrumental Variables Approach”

3 Malcom, et al, (May 2003) “Absence from School: A study of its causes and effects in seven LEAs”

Trude Havik, Edvin Bru, and Sigrun K. Ertesvåg, (2014) “Assessing Reasons for School Non-attendance”

Gil Keppens and Bram Spruyt, (2017) “Towards a typology of occasional truancy: an operationalisation study of occasional truancy in secondary education in Flanders”

4 For example; Ken Reid, (November 2008) "The causes of non-attendance: an empirical study."

Malin Gren-Landell, Cornelia Ekerfelt Allvin, Maria Bradley, Maria Andersson, and Gerhard Andersson (2015) "Teachers' views on risk factors for problematic school absenteeism in Swedish primary school students."

Christopher A. Kearney, Carolina Gonzálvez, Patricia Graczyk, and Mirae J. Fornander (October 2019) “Reconciling Contemporary Approaches to School Attendance and School Absenteeism: Toward Promotion and Nimble Response, Global Policy Review and Implementation, and Future Adaptability (Part 1).”

5 Kenneth Smythe-Leistico and Lindsay C. Page, (2018) “Connect-Text: Leveraging Text-Message Communication to Mitigate Chronic Absenteeism and Improve Parental Engagement in the Earliest Years of Schooling”

Joshua Childs and Ain A. Grooms, (2018) “Improving School Attendance through Collaboration: A Catalyst for Community Involvement and Change”

Teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi – what are schools doing?

The Treaty of Waitangi (the Treaty) forms part of New Zealand’s constitution, the Education Act and The New Zealand Curriculum (The NZC). The recently passed Education and Training Act, 2020 (which replaces the 1989 Act) aims to give greater prominence and effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi at both a national and individual school level. Under the new Act, School Boards from the beginning of 2021 have new objectives relating to Te Tiriti o Waitangi including emphasising the importance of local history and practices through the curriculum; improving the teaching of te reo and tikanga Māori and contributing to the Crown’s duty to actively protect tino rangatiratanga rights.

The social sciences learning area of The NZC is about how societies work and how people can participate as critical, active, informed and responsible citizens. Students explore the bicultural nature of New Zealand society embodied in the Treaty of Waitangi. Students learn about people, places, cultures, histories and the economic world within and beyond New Zealand. They also learn about how the diverse cultures and identities of people affect their participation within their communities. This learning provides opportunities to compare and contrast the role of the Treaty in shaping our bicultural context with other contexts beyond New Zealand.

The Treaty is also an achievement objective at curriculum Level 5 of the social sciences learning area in the NZC: “Students will gain knowledge, skills and experience to understand how the Treaty of Waitangi is responded to differently by people in different times and places”. In other levels of the social sciences learning area, there are opportunities for teachers to incorporate learning about the Treaty. For example, at curriculum Level 1 “Students will gain knowledge, skills and experience to understand how the past is important to people”.

How many schools are teaching about the Treaty?

In 2012, ERO reported increased evidence of the Treaty in the school and classroom curriculum. In Term 4, 2019, information about how the Treaty was being taught from a sample of 20 secondary schools via a questionnaire and from 94 primary and intermediate schools during their regular educational review.

More than 80 percent of the schools reported they included some aspects about the Treaty in their curriculum across year levels. However, for the majority of these schools these aspects were limited to teaching about the Treaty principles (partnership, protection and participation) rather than teaching explicitly about the history, content and implications of the Treaty.

Approximately half of the schools we talked to clearly linked their teaching about the Treaty to curriculum achievement objectives. A quarter of these schools reported against a learning outcome related to students’ understanding of the concept and importance of a treaty. We found it was rare for schools to review their approach to teaching about the Treaty.

What did teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi look like in primary and intermediate levels?

The following table shows what was typically taught in the primary and intermediate schools which reported teaching detail about the Treaty as students progressed through their schools.

|

Typical content taught across year levels |

Teaching about the Treaty |

|

Years 1-2: The value of a shared understanding of the values and culture and the process of developing a classroom treaty |

Students did not learn specifically about the Treaty but were learning about the importance of developing an agreement about treating each other with respect, setting expectations, reaching consensus, and appreciating different opinions. Karakia, pepeha, waiata, haka and te reo Māori were increasingly used in class. |

|

Years 3-4: History of the Treaty |

Students began to learn about the Treaty’s history: why it was created, who signed it, when and why it was signed. Some schools focused on the three principles (partnership, protection and participation) and what these mean for individuals, their peers and their class culture. |

|

Years 5-6: The importance and implications of the Treaty to develop a deeper understanding |

Students further unpacked the Treaty: why it is important, what it means to different people (tangata whenua and pākehā), including their rights and responsibilities. Some schools made connections with their Māori whānau or local community and invited them to share their knowledge of the local context. |

|

Years 7–8: Māori concepts and other aspects of the Treaty such as biculturalism |

In some schools, students worked on inquiry topics about the Treaty such as kotahitanga (unity), the connections with the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) and Rangiaowhia (Ngāti Maniapoto local history). They also learnt more about valuing language and culture, diversity and biculturalism.” |

Lower decile schools and schools with 25 percent or more Māori students were more likely to teach about the Treaty. For example, lower decile schools were more likely to teach specifically about the Treaty in Years 7-8 than high decile schools. Some of these schools were also better at identifying specific learning objectives and outcomes linked to teaching about the Treaty.

In some schools, teachers worked together to develop an understanding of their obligation to the Treaty by encouraging and supporting biculturalism; for example, the whakataukī in one primary school was ‘He waka eke noa’: we are all in this waka together. Students discussed the meaning of the whakataukī and the need to work together (mahi tahi), what this means for them and how it can work in their class. Together they developed a classroom treaty about their expectations for behaviour, attitudes and actions which helped students to ground their understanding of a Treaty.

What did teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi look like in secondary schools?

In secondary schools, learning about the Treaty was mainly through the social sciences curriculum. In Years 9 and 10, these studies focused on creating contextual knowledge about the history and place of the Treaty in the school’s local community. This generally included the exploration of interactions between tangata whenua and pākehā, how they adapted to living together, including developing an appreciation of their different world views.

Most secondary schools developed their Years 11-13 social sciences curriculum to deliberately give students choice about the context for their learning. For example, one Year 12 history task1 requires students to carry out an inquiry of a historical event or place that is of significance for New Zealanders. Students can choose any New Zealand event from about 30 selected contexts, of which the Treaty of Waitangi is one.

The New Zealand History Teachers’ Association is committed to including more Māori history in the curriculum. In 2018, they developed a unit for Year 12 history students focused on the Bastion Point protests and understanding the significance of signing the Treaty of Waitangi in modern day challenges. In late 2019, a few schools had used this unit as the basis for their Year 12 history assessments.

Some schools reported they were teaching aspects of the Treaty in other learning areas. For example, a few schools integrated Māori concepts like rangatiratanga, pūtake and kaitiakitanga in Business Studies and Science to support students’ understanding of Māori worldviews of leadership, entrepreneurship and stewardship, respectively.

Learning about the history and place of the Treaty in the local community was at the core of programmes offered by schools teaching te reo Māori. Some of these schools also developed partnerships with the local iwi/marae and included kaupapa/kōrero about the students’ tribal affiliations in their programme.

What resources can support schools’ teaching about the Treaty?

Generally, schools used resources they felt were appropriate from the Ministry of Education and Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage to inform their teaching programmes. Primary and intermediate schools used a variety of resources, such as The Tree Hut Treaty. However, very few of them used the Ministry of Education’s resource Te Takanga o te Wā: Māori History Guidelines for Year 1-8. The Ministry of Education has recently collated resources in Social Sciences Online and these include a featured resource about Hītori Māori | Māori history. Secondary schools were more likely than others to use online and other resources, including making links to iwi education plans.

Where in-school knowledge was weak, some schools engaged with external experts to provide advice and guidance. Some of these schools accessed resources produced by their local community like Kā Huru Manu or resources from New Zealand History and Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Other schools used resources from the Tuia Mātauranga national education programme and Bridget Williams Books collection.

The majority of schools reported having no or limited links with their local iwi or marae. However, most schools said they were open to building those relationships. Such connections could help them develop the local content of their curriculum and complement any local iwi education plan.

About 30 percent of schools wanted professional learning and development (PLD) specific to the Treaty. Ideally, they sought support to build and apply context knowledge and wanted to work with other practitioners to devise, test and review teaching programmes and assessments about the Treaty.

About 40 percent of primary and intermediate schools that wanted more resources asked for more child-friendly and accessible content, particularly focused on teaching about the Treaty.

Teaching about the Treaty of Waitangi is richer when it is more than just about the contents of an agreement

From this study we observed that by making teaching and learning about the Treaty more than just about an agreement, some schools brought the Treaty to life and students learnt about:

- the history prior to the signing of the Treaty such as the New Zealand’s 19th century wars

- the first signing and later signings of the Treaty

- the difference between Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Treaty of Waitangi

- the Treaty as a founding document and part of New Zealand’s constitution, and the three broad principles of partnership, protection and participation

- the significance and implications of the Treaty in the current discourse about Parihaka, Bastion Point protests, Ihumātao land conflict and related local events

- other aspects of the Treaty such as biculturalism, te ao Māori including te reo Māori

- Māori concepts such as rangatiratanga to help them understand Māori world views of such ideas.

ERO found good examples of how some schools brought the Treaty to life in their programmes. For example, geography students in an Auckland school were required to complete an assessment that explained aspects of a contemporary geographic issue. Teachers were strategic in their choice of the land conflict at Ihumātao in Mangere as the topic of inquiry. Students visited Ihumātao and talked with one of the main protestors. They were expected to examine different and contrasting perspectives of the land conflict at Ihumātao. This helped them to explore and gain an appreciation of the significance of the Treaty in today’s thinking and decision making.

Schools can build on their current programmes by teaching about the history, content, impact, and ongoing significance of the Treaty across the curriculum. From the information we gathered it indicated that understanding and appreciating the significance of the Treaty occurs best when students are learning about it in contemporary contexts. This can be approached through familiar social issues, land rights, or environmental issues, where the Treaty plays a pivotal role.

1 Current practice for history assessment AS91229 as outlined in the NZQA website.

School evaluation indicators: How they help us understand the education system

A growing desire for systems evaluation

The recent Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce report emphasised the need for increased evaluation of education system performance in New Zealand. The Government’s response to the review confirmed that ERO will increasingly undertake evaluation and assessment to provide system level insights:

ERO… will ensure their… research and evaluation functions provide a strong basis for generating effective system level information and evaluation that informs prioritisation, action, and improvement.

This article explores how aggregated information from ERO’s school reviews can inform our understanding of education system performance.

How does ERO make a judgment about a school?1

In recent times, ERO has provided the school and its community with a report after completing a review, which includes an overall judgment of how well the school is achieving and supporting students to succeed. A school could receive a judgment of “needs development”, “developing”, “well-placed” or “strong”.

The high-level overall judgments are informed by ERO’s school evaluation indicators. These indicators represent what we know from the research evidence about great schools, and reviewers use their judgment to evaluate how close schools are to achieving this goal for each indicator.

The school evaluation indicators are split broadly into outcomes and processes. Outcome indicators are focused on learners and include student outcomes such as progress and achievement. They assume a holistic approach to learners’ wellbeing, development and success. Process indicators describe the conditions and practices that contribute to school effectiveness and improvement, such as stewardship, quality teaching or internal evaluation.

How can the school indicators support systems evaluation?

Traditionally, school evaluation indicator judgments have only contributed towards a school’s overall review judgment. However, these indicator judgments contain a wealth of information about specific areas in which schools are performing well or may need further development. When indicator judgments are compared across many schools, we can identify strengths and areas in need of development across the education system.

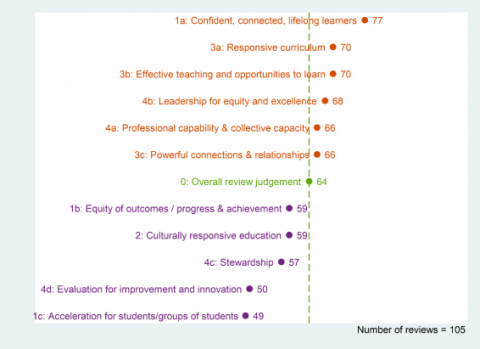

In this article we look at 105 school reviews to see how ERO review teams assessed performance across three student outcomes and eight school processes. This sample is made up of reviews completed during term 4 2019 and the beginning of term 1 2020.

What we found

Schools received an overall judgment of well-placed or strong (ERO’s two highest judgments) in 64 percent of reviews. However, the judgment on specific student outcomes and school processes varied substantially. These results are summarised in the figure below, which shows the percentage of schools which were judged as well-placed or strong for each of the student outcome and school process domains, across the 105 reviews analysed.

Figure 1: Percentage of schools that received an overall judgment of well-placed or strong in student outcome and school process domains

Schools in this study performed the best on the student outcome “Confident, connected, lifelong learners”, with 77 percent of schools judged as well-placed or strong. Other well-performing indicators were “Effective teaching and opportunities to learn” and “Responsive curriculum”, with 70 percent of schools being judged as well-placed or strong for each of these processes.

At the other end of the spectrum, two indicators stand out as areas for development. Only 49 percent of the schools in this study received a well-placed or strong judgment for the student outcome indicator “Acceleration for students/groups of students”. Similarly, only 50 percent of the schools received the rating of well-placed or strong for the school process indicator “Evaluation for improvement and innovation”.

ERO has undertaken work to build school capability for effective internal evaluation and accelerating student achievement in recent years, largely through the development of resources intended to guide schools’ improvement.

In 2015, ERO released the publication Effective school evaluation: How to do and use internal evaluation for improvement, alongside a companion good practice report. These resources describe what effective internal evaluation is, what it involves, and how to conduct it in ways that will enhance educational outcomes for students.

Schools and their communities need to be continuously evaluating the impact of their endeavours on learner outcomes. To do this, they need strong leadership and evaluation expertise. Their systems, processes and resources should support purposeful data gathering, collaborative inquiry and decision making, and align closely with the school’s vision, values, strategic direction, goals, and equity and excellence priorities.

In 2014, ERO provided guidance on student acceleration in the publication Accelerating student achievement: A resource for schools. This report details how schools can:

- create a plan to support students to improve their results

- carry out additional assessments with students who need to accelerate their progress, to better understand their strengths and needs

- build “educationally powerful connections” with students, their parents and whānau.

Effective internal evaluation and accelerating student achievement are also linked. Internal evaluation is needed to identify and support students to accelerate their achievement by monitoring student progression, as well as to identify teaching strategies that have successfully accelerated student achievement.

Additional insights on the school system

As part of a holistic systems evaluation, the school evaluation indicators can guide and inform complimentary evaluations and research to generate meaningful change and improvement.

The above findings indicate that knowing ‘what to do’ may not be enough for improving internal evaluation or student acceleration. Rather, other factors may limit schools’ ability to undertake these processes effectively. For example, schools may not have the necessary capacity or capability required to improve these processes.

As changes to the education system are made, analyses of ERO’s school evaluation indicators judgments can also inform evaluations of new initiatives or approaches. A large increase in the number of schools judged to be doing well on a given indicator lends support to the effectiveness of an initiative, while no change or a decrease could reflect the introduction of ineffective initiatives.

Conclusion

ERO’s school evaluation indicators contain a wealth of information about education system performance in New Zealand schools. Internal evaluation and accelerating student achievement were both identified as areas in need of improvement, across the schools examined in this article. School leaders can utilise ERO’s existing publications to guide their improvement in these areas.

Looking forward, this previously untapped source of system-level information can also be used by ERO to inform prioritisation, action, and improvement of the education system. Over time these indicators can be used to monitor changes in system performance and to evaluate new initiatives.

1 ERO is currently changing its operating model for school reviews (see Working with the sector to refine the new model for school reviews), however the indicator framework described here remains a common core of any evaluation approach.

Leadership Partners pilot programme enables meaningful exchanges

ERO’s Leadership Partners programme launched in late January with a pilot group of six school leaders. The Partners trained alongside and then joined ERO Review Officers in conducting external school evaluation processes during term one. They’re continuing to work alongside Review Officers and schools as we use our interim methodology to learn about schools’ Covid-19 responses.

The Leadership Partners programme is a joint initiative between ERO and the education sector, and is supported by key sector groups (SPANZ, NZPPF, NZAIMS and NZSTA). It aims to build strong, enduring partnerships and networks between ERO and the sector, build school leaders’ understanding of evaluation for improvement through upskilling practitioners in ERO’s work, and enhance the review process for both schools and ERO.

Early feedback has been that Leadership Partners play a valuable role during ERO evaluations, bringing more diverse expertise to the evaluative process and allowing ERO to benefit from the valuable insights and knowledge of current practitioners.

Our pilot Leadership Partners also benefit from developing deeper insights into their own schools through contributing to the review of others. One partner has commented that the ERO Leadership Partners induction process “was some of the best professional learning I have ever had”.

A second tranche of school leaders will join the programme in September 2020, and the programme will be evaluated with a view to expanding it in 2021.

Look out for advertised opportunities to join the 2021 programme in the Education Gazette in term four, and check out our Leadership Partners page, where school leaders talk about their experiences working alongside ERO and how learning more about external evaluation has benefited them and their schools.

Meet the Team: Jane Lee

Jane has previously worked in ERO as Regional Manager – Review and Improvement Services for the Southern Region and as National Manager Projects. Jane has worked in education for more than 30 years, including as a teacher, special education advisor, Review Officer and at the Ministry of Education focusing on Special Education. She is particularly interested in Māori education, and is committed to improving education so that all children experience high-quality teaching and learning.

Jane holds teaching qualifications, a degree in education and is nearing the completion of her Master of Public Management. She is of Kai Tahu, Kati Mamoe and Waitaha descent. Jane and her whānau connect to their heritage through fishing and the annual harvest of titi – which also allows them a short escape from technology.

Discontinuation of ERO’s audits for the Teaching Council

ERO will no longer undertake Teaching Council Audits, as of 30 June 2020. The existing contract between the Teaching Council and ERO concluded at the end of the financial year.