Summary

Each year, Alternative Education provides education to over 2,000 young people who have been disengaged from education and who have high and complex needs. Many are exposed to crime, violence, and trauma, and just under a third have a mental health need. Almost two in five have been referred to attendance services and one in four have been suspended.

The Education Review Office (ERO), in partnership with the Social Wellbeing Agency (SWA), has looked at how well the education system is supporting young people in Alternative Education.

This study describes what we found and what is needed to significantly improve education for these young people.

Whole article:

An Alternative Education? Support for our most disengaged young people - SummaryWhat is Alternative Education?

Alternative Education is an educational intervention provided to secondary school learners who are disengaged or alienated from school, and who are unlikely to be able to learn productively in school.

The aim of Alternative Education is to provide young people with a quality education and to support them into education, training, or work.

Young people in Alternative Education are taught by educators, who do not have to be registered teachers. They are taught in small groups, often with a ratio of one educator to around 10 young people. They are usually taught by one or two educators and do not have to rotate around classrooms. They are not usually on school grounds. They can be in community houses, youth facilities, or with tertiary training providers.

What does good education look like for these young people?

Quality teaching practices in Alternative Education recognise that many of the young people have experienced trauma and have a range of needs. To thrive in Alternative Education, young people need educators to address both their education needs and their broader needs.

Like all learners, young people in Alternative Education need quality teaching.

This evaluation looked at education provision for young people who attend Alternative Education. We answered three key questions:

- Who are the young people in Alternative Education and what are their outcomes and experiences?

- How good is Alternative Education provision?

- What changes are needed to strengthen provision?

Who are the young people in Alternative Education, and what are their outcomes and experiences?

Young people in Alternative Education are the most highly disengaged from education. Many are exposed to crime, violence and trauma, and just under a third have a mental health need. Many are in the Youth Justice system. They are 25 times more likely than other young people to have had a Family Group Conference.

- Almost one in three (31 percent) of young people in Alternative Education have been referred to a specialist mental health service. This is more than four times more likely than the rest of the population.

- One in 12 (8 percent) of young people in Alternative Education have had a Family Group Conference in the Youth Justice system, 25 times more likely than the rest of the population.

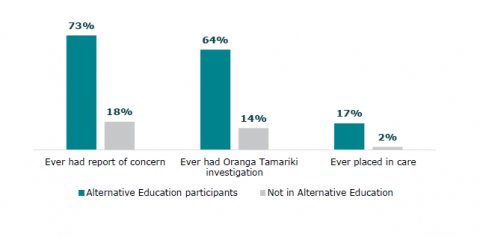

- Young people in Alternative Education have high involvement with Oranga Tamariki. One in six (17 percent) of young people in Alternative Education have been in the care of Oranga Tamariki, nine times more likely than the rest of the population.

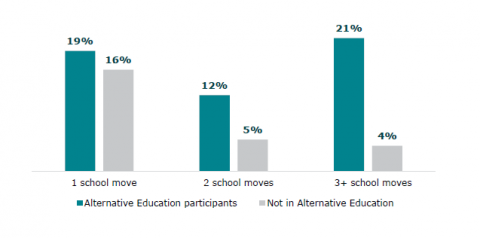

- Young people in Alternative Education have high levels of transience – one in five have moved schools three or more times before starting the at Alternative Education.

Figure 1: Involvement with Oranga Tamariki: Alternative Education participants and young people not in Alternative Education

Figure 2: School moves: Alternative Education participants and young people not in Alternative Education

“Growing up wasn’t the best. It was a bit rocky in my family, but we got there. I was around gangs my whole life, and violence, drinking, drugs.” - Young person attending Alternative Education

Young people in Alternative Education are disproportionately Māori and male, though providers reported the number of females has increased recently.

- Seven out of 10 (68 percent) young people in Alternative Education are Māori, compared to 24 percent outside of Alternative Education.

- Six out of 10 (63 percent) of young people in Alternative Education are male, compared to 51 percent outside of Alternative Education.

Young people are often referred to Alternative Education due to behaviour. Over a quarter have been suspended or excluded. They are also referred due to attendance issues, and alienation from school. Sometimes they are referred by Youth Justice or Oranga Tamariki.

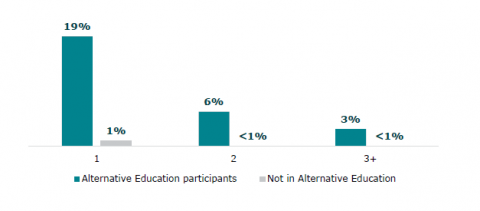

- Many young people in Alternative Education have been suspended or excluded. More than one in four (27 percent) have been suspended at least once, which is 22 times more likely than other young people.

Figure 3: Number of suspensions or exclusions: Alternative Education participants and young people not in Alternative Education

- Prior to starting in Alternative Education, two out of five (38 percent) young people in Alternative Education have been referred to Attendance Services. This is over five times more likely than the rest of the population.

“I just stuck up for myself. I just said what I had to say. If I was like an angry mood, I would take it out on them, and I would like want to fight them. So, like, yeah, and then that led to me getting kicked out” - Young person attending Alternative Education

These young people’s needs have not been identified and met early enough. They also have significant gaps in their learning, which have not been addressed. Waiting for a place at Alternative Education deepens the disengagement. This indicates that our education system is not currently set up with sufficient or the right range of provision to meet the needs of these young people.

In the year before they start attending Alternative Education, young people in Alternative Education miss an average of 58 days of school. Educators told us that many young people are working at a level several years below their age – for example, at Year 4 or 5 level (age 8 – 10), even though they are 13 – 16 years old.

“These young people come to college with poor attendance from primary. They missed out on learning in primary” - Contract-holding school leader

While in Alternative Education, these young people attend more, enjoy learning more, feel safer, have a stronger sense of belonging, and improved behaviour.

- Fourteen of 22 whānau report their young person attends Alternative Education more than they attended their previous school. There is no national attendance data for young people in Alternative Education.

- Three out of four (76 percent) young people in Alternative Education prefer it to their previous school.

Four out of five (84 percent) young people in Alternative Education have a tutor they like, and four out of five (83 percent) have someone who cares about them.

When they move out of Alternative Education, only around one in four return to school. More than half do not go on to further training or employment. By age 20, almost 70 percent are receiving benefits.

- Only three in 10 (28 percent) young people who attend Alternative Education are attending tertiary education at age 18, and by age 24 this drops to one in 10 (11 percent).

- At age 24, almost two-thirds (63 percent) of people who had attended Alternative Education were receiving a benefit, compared to half of adults (51 percent) with similar backgrounds, but who never went to Alternative Education (matched comparison group).

Alternative Education does not provide good outcomes. These young people have significantly worse outcomes than other young people, worse even than very similarly disengaged young people with high needs. They are very unlikely to achieve an education qualification. As adults, they are much more likely to be receiving benefits and be involved in the criminal justice system.

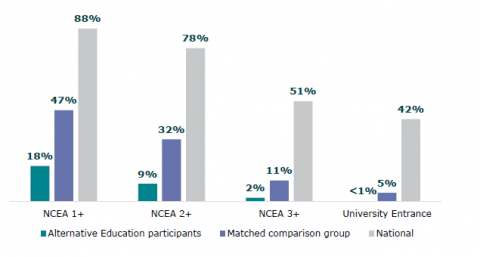

- Less than one in five young people from Alternative Education achieve NCEA Level 1 or higher (18 percent), compared to nine out of 10 other young people.

- Less than one in 10 young people from Alternative Education achieve NCEA Level 2 or higher (nine percent), compared to eight out of 10 other young people.

Figure 4: Attainment of NCEA qualifications: Alternative Education, matched comparison group, and national figures

How good is Alternative Education provision?

The current model of Alternative Education is inadequate to meet the level of need of these often highly disengaged young people, leading to worse outcomes than for other young people:

- Teaching is weak and teaching resources are inadequate. Only one in five educators in Alternative Education are registered teachers.

- Facilities are often so run down they act as a barrier to learning. We visited 20 Alternative Education provision sites and found four operating out of poor-quality facilities and 2 out of inadequate facilities.

“So they were in the most run down building… and it was not a space that had any mana, or had any respect for the students in it. It was not adequate for the needs” -Contract-holding school leader

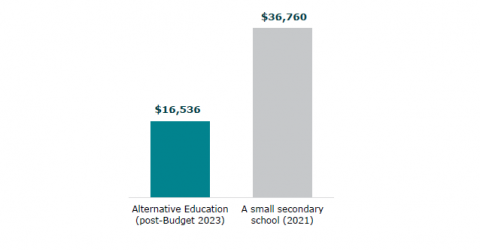

- Funding is inadequate. Budget 2023 recently allocated an additional $25.216 million over four years to Alternative Education, to increase the funding per place to $16,536. This is less than the funding in some small secondary schools.

Figure 5: Funding per place (This is an example of one small school (with 29 learners) in 2021.)

“[To] get that money… to pay four staff we have to fundraise throughout the course of the year on top of our full time jobs to make sure that our staff receive a salary” -Alternative Education Provider

- Funding limitations make it unviable for many providers, and provider and staff turnover is high.

- Providers are isolated from other providers and schools, so they often lack access to broader education resources (e.g. careers advice, specialist subjects, sports) and professional teaching support.

- Providers cannot always access the broader wrap-around support young people need.

- Accountability for delivery and outcomes is weak.

“We do not have access to RTLB [Resource Teacher: Learning Behaviour] or learning support specialists.” -Alternative Education leader

hen young people (exceptionally) do succeed at Alternative Education it is due to the elements of the model that do work.

- Small class sizes

- Young people reported the smaller class size at Alternative Education was a critical element in their feeling safe and able to learn.

“It’s been way easier, because I’m around, you know, not so many kids. And I know all these kids. And there’s only like two teachers… So it’s actually easier for me, and I actually do good with a little group of people” - Young person enrolled at Alternative Education

- Having the same educator throughout the day

- We heard that getting to know their educators and be known by them meant young people felt cared for and supported

- The flexibility to provide a different education on a site separate from school

- Young people engaged enthusiastically when their learning was meaningful to them. Their poor experiences of school mean it is important that Alternative Education is different to school.

“A lot of our guys been really burnt by schooling. So trying to give successes, and safe ways they can engage with schooling, so they don’t feel dumb” - Alternative Education Educator

- Having staff with experience, aptitude, and commitment to working with these young people, who act as positive role models.

“The tutors understand us… they’re just always there for us” - Young person enrolled in Alternative Education

These elements need to be combined with a model enabling quality education, wrap‑around support, and a range of pathways.

Alternative Education is potentially a missed opportunity to change these young people’s life trajectories. They are often engaged and attending, but the current model of provision is failing to provide them with a quality education and may be contributing to poorer outcomes. The long-term costs for the young person, their family, and broader society are very significant.

What changes are needed to support provision?

This study has found that there is a group of young people who have high and often complex needs, and are highly disengaged or at high risk of disengaging from education. It has also found that we need to provide these young people with a better education. ERO recommends action across five areas.

Area 1: Better identify and meet the needs of these young people before they become disengaged, and increase the number who are able to stay and succeed in mainstream schooling.

1. The Ministry of Education provide guidance on how to effectively identify young people most at risk of disengagement, and support schools to better identify these young people.

2. Having identified young people most at risk of disengagement, the Ministry of Education support schools to act early to enable them to stay and succeed in school, including increasing awareness of:

- the predictive risk factors for being referred to Alternative Education

- models of practice and intervention that support young people’s continued engagement in education

- where and how flexibility can help with inclusion for young people at risk of disengaging

- how to access support to address issues, including connecting with other services and programmes that provide more intensive support and links to other tools and resources that may help.

3. ERO and the Ministry of Education identify and share with schools best practice in managing challenging behaviours in the classroom to enable more young people to stay in school.

Area 2: Make sure there are a range of effective options (of different type, intensity, and duration) available for those young people who are not thriving in the school setting and that there are clear, consistent, and rigorous gateways so that young people are matched to provision that best meets their needs.

4. The Ministry of Education examine the range of options available for those young people who are not thriving in the school setting, how well they meet the range of needs and are complementary, and how clear and consistent the criteria for referral are.

5. To support decisions, made with whānau, on which education options are suitable for a young person, the Ministry of Education develop guidance for all schools that includes:

- the range of options for education outside of schooling

- the types of learners that each of the options are most suitable for

- how to access each of the options and eligibility requirements

- what is needed for good transition into different education settings, including having a plan for information to follow the learners

- the role of all agencies in each of the options.

Area 3: As part of this set of options, reform the ‘Alternative Education’ model of provision so that there is a new model that is designed to meet both the education and broader needs of the most disengaged young people who need an alternative to mainstream schooling.

6. The Ministry of Education develop a clear national model and set of standards for high quality ‘Alternative Education’ provision that includes:

- funding that is sufficient to meet the depth and complexity of needs of this group

- a funding model that allows for greater oversight and accountability

- a national model of teaching practice that is based on the evidence of teaching approaches that work for young people who are the most disengaged from learning

- a requirement for providers to have qualified, registered teachers

- a requirement for small class sizes and continuity of teacher or tutor

- access to the broad range of education expertise and resources across education providers so young people can access education programmes and pathways that match their interests

- skilled support workers to provide wrap-around support for the young people and to broker access to specialist support to meet young people’s broader needs

- kaupapa Māori approaches that enable Māori young people to succeed as Māori.

7. The Ministry of Education to ensure all current and future ‘Alternative Education’ provision has suitable premises and facilities – in line with the expectations for other learning environments.

8. The Ministry of Education supports teachers in ‘Alternative Education’ with a lead of professional practice, curriculum resources tailored for young people in ‘Alternative Education’, and facilitated professional networks.

9. The Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Oranga Tamariki, Whaikaha | Ministry of Disabled People and Ministry of Social Development work together to ensure young people in ‘Alternative Education’ are a priority for the specialist support they need.

Area 4: Put in place the support needed for successful pathways and transitions from ‘Alternative Education’ into further education, training, or employment.

10. The Ministry of Education, Tertiary Education Commission, Ministry of Social Development, Whaikaha | Ministry of Disabled People, and Oranga Tamariki review the transition and ongoing support for young people in ‘Alternative Education’ to ensure young people have a planned and supported pathway, with sufficient pastoral and learning support, to make a successful transition into further learning or work.

Area 5: Strengthen accountability and monitor how well provision is meeting the needs of young people who are in ‘Alternative Education.’

11. The Ministry of Education actively monitor the quality of provision in ‘Alternative Education.

12. The Ministry of Education report annually on the education experiences and outcomes for young people in ‘Alternative Education,’ including:

- number of young people referred to ‘Alternative Education’

- wait times for entry to ‘Alternative Education’

- number of young people who receive a place and go on to attend ‘Alternative Education’

- attendance of young people in ‘Alternative Education’

- achievement of young people in ‘Alternative Education.’

13. The Ministry of Education ensure ‘Alternative Education’ providers and contract-holders collect and report reliable data on young people’s enrolment, education outcomes, and destinations.

14. The Ministry of Education reports back to the Minister of Education, and Ministers with responsibility for Oranga Tamariki and Youth Justice, on progress made in response to these recommendations by June 2024.

Conclusion

Together these recommendations have the potential to significantly improve education experiences and outcomes for disengaged learners. Improving education for these young people can dramatically improve their lives and life course. It will take coordinated and focused work across the relevant agencies to take forward these recommendations and ensure change occurs. We recommend agencies report to Ministers on progress by June 2024.

If you want to find out more about our evaluation of education for young people in Alternative Education, you can read our report: An Alternative Education? Support for our most disengaged young people.

If you want to find out more about how we used the Integrated Data Infrastructure in this work, you can read the Social Wellbeing Agency report: Experiences and outcomes of Alternative Education participants: An IDI analysis supporting an evaluation of Alternative Education.

What ERO and SWA did

To find out about young people’s experiences, and the quality of provision of Alternative Education, we did:

- site visits and observations of teaching and learning at 22 Alternative Education settings, managed by 11 different contract-holding schools

- 53 interviews and 124 surveys of young people in Alternative Education

- 19 interviews and 23 surveys with whānau of young people in Alternative Education

- 65 interviews and 65 surveys of leaders, tutors, and teachers at Alternative Education

- 44 interviews and 128 surveys of school leaders (including leaders of schools young people in Alternative Education may be enrolled at, and contract-holding schools)

- Analysis of documentation from agencies and providers

- interviews with key informants in the Alternative Education sector.

We used the IDI to:

- describe the characteristics, contexts, and prior experiences of Alternative Education participants

- use the characteristics, contexts, and prior experiences to identify a matched comparison group of similar young people who never participated in Alternative Education

- describe the future outcomes and activities (age 17 – 30) of people who previously participated in Alternative Education, compared to the matched comparison group.

These results are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) which is carefully managed by Stats NZ. For more information about the IDI please visit https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/.

The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Stats NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994 for statistical purposes. Any discussion of data limitations or weaknesses is in the context of using the IDI for statistical purposes, and is not related to the data’s ability to support Inland Revenue’s core operational requirements.