Summary

More than a third of our principals have less than five years’ experience in the role, and it’s important that they are set up for success. ERO looked at pathways and supports for new principals.

We found that leadership experience before becoming a principal makes a difference, but there are no clear or recommended pathways for new and aspiring principals to gain the experience they need. Development and support helps, but there are still areas of the role in which new principals feel unprepared, and where they are not confident to carry out their responsibilities once in the role. We make a range of recommendations to improve how new and aspiring principals can be set up for success.

Whole article:

'Everything was new': preparing and supporting new principals - SummaryERO looked at how new principals move into the role (before being appointed), as well as their first five years of being a principal. We heard from new principals, as well as key experts and school boards who work closely with new principals. We were interested to find out what pathways and supports look like currently, and the impact that these are having on principals’ preparedness and confidence in the role. We also suggest areas for improvement around these pathways and supports.

Who are our new principals?

In 2022 a third of principals are new principals, this is a big increase

When we talk about ‘new principals’, we mean those who have been in a principal role for less than five years. This is more than a third of our total principal population. We focused on new principals from schools across Aotearoa New Zealand, in both primary and secondary schools.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s principal population is changing, with more experienced principals retiring, leading to a big increase in the proportion of our principals that are in their first five years in the role. In 2022, new principals made up 37 percent of all principals, up from 27 percent in 2014. As the principal workforce is losing experienced leaders, it is crucial that our new principals are well prepared for principalship, and confident once in the role.

There are about 860 new principals. Our new principals are more likely to be Māori, to be younger, to be female, and to represent diverse cultures and ethnicities. Two‑fifths of new principals work in small schools.

What is the role of a principal?

The principal role is crucial to quality education

Effective principals are vital for achieving positive, equitable outcomes for learners. Research evidence shows that the quality of principalship has the biggest influence on learner outcomes, after classroom teaching.

The principal role can be very rewarding but is complex and can differ between schools, particularly between school types and sizes, rural and urban settings, diversity of learners and communities, and more.

ERO focused on 11 key areas of the principal role:

- giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi throughout the school

- working in partnership with whānau Māori, hapū, and iwi to develop a localised curriculum that is inclusive of mātauranga Māori

- establishing and maintaining a clear shared vision, strategic direction, and goals for the school

- building and maintaining positive, effective relationships with staff and learners

- building and maintaining positive, effective relationships with the school community

- ensuring the delivery of high-quality teaching practice and curriculum across the school

- working with data to monitor and evaluate teaching and learning

- working closely with diverse families and community groups to promote inclusion for all learners

- managing the school’s resources, for example finances, employment, timetabling, and property

- working effectively with the school’s board members

- ensuring the school complies with all legislative and policy requirements.

Key findings

1. How prepared are new principals?

New principals are not always well prepared for all aspects of their new role

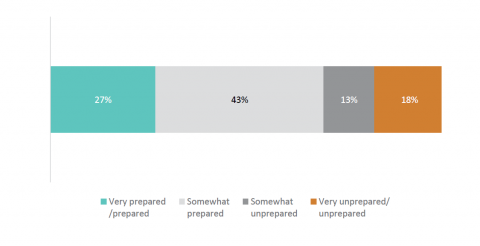

- Only a quarter of new principals (27 percent) are prepared or very prepared for the role overall when they start.

- The complexity of the role, and the reality of the school they start in, are the two main reasons new principals arrive feeling unprepared, anxious, or surprised.

- The areas in which they are most prepared are building and maintaining relationships with staff and learners, and building relationships with the school community.

- The areas in which they are least prepared are working in partnership with Māori, and the administrative and legal aspects of the role. For example, only 22 percent of new principals report being prepared for working in partnership with Māori.

Figure 1: How prepared principals felt when they first started their role

“You move from being a teacher or a deputy principal, which is still pretty kid- and teacher-facing, to you to being the CEO of in most cases a multi-million dollar organisation.” - Expert

2. What are the pathways to become a principal?

Prior experience in a leadership role is the best pathway. Most, but not all, principals follow this pathway.

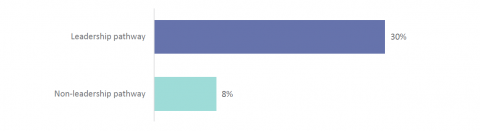

- New principals who have previously held a school leadership role are over three times more likely to be prepared for the role. ERO asked about senior leadership or middle-management experience – roles like deputy principal, assistant principal, syndicate leader, head of department, faculty leader, leader of learning, specialist teacher, special education needs co-ordinator, learning support coordinator, or holding other management units.

- The overwhelming majority of principals (88 percent) have held a leadership role before reaching principalship, but one in 10 have not.

“[In my] Deputy Principal role I had lots of opportunities to be involved in lots of different aspects of leadership - especially working with staff." – New principal

Not all those teachers who have the potential to be principals are encouraged into or aware of the pathways to become principals.

- Principals reported to us that identification and support for future principals is too often left to chance.

“It was more the leaders around me recognising the skills that I didn't know that I had. So I had my principal … he was the first one that approached me and sowed the seeds of trying to take on more leadership responsibilities. And at that point, I didn't think that I had the skills or the capacity to do that. And it was him, I guess, mentoring and encouraging me to take on extra responsibilities.” – New principal

Figure 2: Percentage of principals who felt prepared or very prepared for their role, by the pathway they took

3. What difference does development and support make?

Development and support helps aspiring principals prepare.

- Development and support makes the biggest difference for preparedness in planning, managing resources, using data, delivering the curriculum, and working with Māori.

- It makes the least difference for preparedness in managing relationships with the school community and working with the school board.

Coaching and mentoring, and postgraduate programmes make the most difference to new principals’ preparedness.

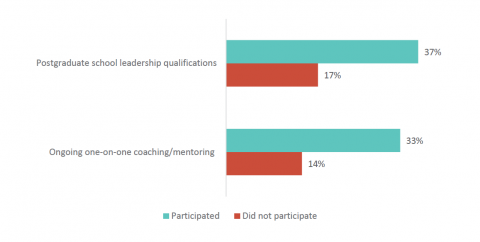

- Two-thirds (67 percent) of new principals access coaching/mentoring, and half (49 percent) gain postgraduate school leadership qualifications before they start in the role.

- New principals who had participated in these programmes are twice as likely to report being prepared for their roles.

Figure 3: Percentage of new principals who felt prepared or very prepared by their participation in postgraduate school leadership qualifications and ongoing on-on-one coaching/mentoring prior to becoming principal

4. How well supported are new principals when they start?

Not all new principals have an induction process when they start in the role and where an induction process does occur, it is of variable quality.

- Fifteen percent of boards in schools with a new principal did not provide an induction and 42 percent did not know if there had been an induction.

- New principals report that the delivery of inductions is inconsistent. Those that experienced inductions report that their usefulness is variable.

5. Do new principals gain confidence once in the role?

Principals’ confidence increases over their time in the role, but there remain key areas where they lack confidence.

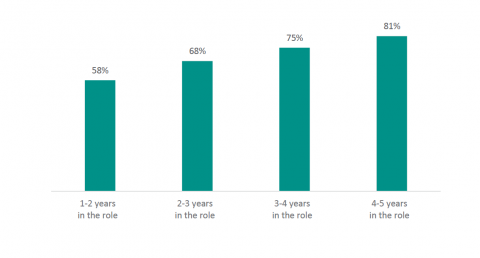

- After 1-2 years’ experience, over half (58 percent) of new principals are confident in their role. By 4-5 years in the role, eight in 10 principals (81 percent) are confident in their role.

- Principals’ confidence grows the most in administration, governance, and direction setting.

- Principals’ confidence grows the least in everyday aspects of teaching and leading (in which they are already confident), partnership with Māori, working with diverse families to promote inclusion, and giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi (areas where they lack confidence). Less than half of new principals are confident to give effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Figure 4: Percentage of new principals who feel confident or very confident by time in role

6. What development and support helps new principals once they are in the role?

Principals report that connecting with peers and more experienced principals and coaches is most useful.

- Nearly all (over 99 percent) new principals continue to participate in development and support opportunities once they are in the principal role, and most engage in a range of opportunities.

- Principals find development and support that involves connecting with others (e.g., coaching and mentoring, collaborative groups, and ongoing programmes) most effective for building their confidence in the role.

- Development and support that involves connecting with others is also most effective for supporting their wellbeing.

“I am so grateful to my fellow beginning principals whom I started with in my Kāhui Ako. I would not have survived without them, and I know they feel the same.” – New principal

7. How well do school boards support their new principals?

School boards are not sufficiently aware of how well their new principals are faring.

- While new principals report a lack of confidence in several areas of their role, school boards rate their principals’ confidence highly across all areas of practice.

- More than two thirds (69 percent) of boards rate new principals’ wellbeing as high or very high, compared to just 23 percent of new principals themselves.

8. What is different for small schools?

Four in 10 new principals are in small schools, but those who start in small schools are less prepared, less likely to have had prior leadership experience, and have accessed less prior development and support.

- Principals who start in small schools are over 10 times more likely to have come through the non-leadership pathway (straight from teaching or other areas of education) than those in large schools. Twenty-two percent of new principals in small schools come from a non-leadership pathway.

- New principals starting in small schools are a third less likely to have participated in development and support before becoming a principal, and also find it less relevant.

- New principals who start in small schools are a third less likely to feel prepared than those starting in large schools. In particular, they are significantly less prepared for administrative and legal responsibilities, delivery of high-quality teaching and curriculum, and strategic planning.

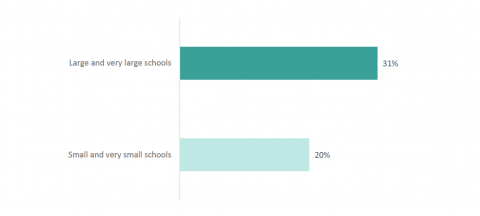

Figure 5: Percentage of new principals who felt prepared or very prepared overall by school size

Once in the role, principals in small schools are less confident, can face barriers accessing the most effective development and support, and report poorer wellbeing.

- Once in the role, new principals in small schools are a quarter less likely to be confident than principals in larger schools. In particular, they are less confident at setting the direction for the school and ensuring the delivery of high-quality teaching practice and curriculum.

- Principals in small schools report having trouble accessing the most effective development and support due to isolation and difficulty getting away from school.

- Thirty-four percent of new principals in small schools report low wellbeing compared to 21 percent in large schools.

“We can't just catch up with someone for a coffee down the road or anything like that … Our ability to connect, other than virtually, doesn't exist.” – Small school principal

9. What is different for new tumuaki Māori – Māori principals?

Tumuaki Māori feel less prepared and are less likely to have had the opportunity to have prior leadership experience.

- Nearly a third (30 percent) of tumuaki Māori feel unprepared when they first start, compared to 14 percent of non-Māori principals.

- Eighty-three percent of tumuaki Māori have had prior leadership experience, compared to 90 percent of non-Māori new principals.

Once in the role, tumuaki Māori are more confident than their peers.

- Seventy-five percent of tumuaki Māori feel confident in the role overall compared to 70 percent of non-Māori new principals.

- Tumuaki Māori are more confident in most (eight out of 11) key areas of practice.

Areas for action

ERO has identified five areas for action that will help ensure new principals are set up to succeed.

|

Area 1: Establish accessible and sufficient pathways for aspiring leaders to become principals. |

|

|

Area 2: Ensure there are sufficient, accessible, and evidence-based development opportunities for aspiring principals. |

|

|

Area 3: Support the delivery of accessible and evidence-based development opportunities once new principals start in the role. |

|

|

Area 4: Prioritise preparing and supporting new principals in small schools. |

|

|

Area 5: Ensure Māori aspiring leaders have clear, well supported pathways into school leadership. |

|

|

Cross-cutting recommendation |

|

Conclusion

New principals could be better supported to move into their role with preparedness and confidence. Identification and support of new leaders, including Māori leaders, is too often left to chance. New and aspiring principals would benefit from clearer pathways into principalship, as well as better opportunities to grow their understandings and experience across the range of important parts of the role. Particular attention needs to be paid to meeting the specific needs of new tumuaki Māori and new principals in small schools.

ERO’s recommendations are designed to better set up our new and aspiring principals for success, for the benefit of Aotearoa New Zealand’s learners.