Summary

This report looks at the impact of Covid-19 on teachers and principals – including how Covid-19 has impacted enjoyment in work and workload. This report also sets out examples of how schools can prepare for 2022 and what supports will be needed for teachers and principals.

Whole article:

Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Teachers and PrincipalsIntroduction

One and a half years after it first arrived in New Zealand, Covid-19 continues to impact our lives. After the first lockdown, learning at school was mostly onsite. However, the more contagious Delta variant means New Zealand now faces the prospect of learning to live with Covid-19 in the community. Teachers and principals have adapted what and how they deliver education in response to extensive disruptions. They will have to continue to adapt as the situation unfolds and be prepared to deal with different disruptions. This report explores the impact of Covid-19 on teachers and principals.

The first nationwide Covid-19 lockdown, which began on 25 March 2020, saw the closure of all schools and other educational facilities. Learning moved from the classroom into the homes of students around the country. This was a new experience for everyone, and it posed unique challenges.

While most schools were back in the classroom from May 2020, disruption from the Covid-19 pandemic continues. In August 2021, the spread of the more infectious Delta variant of Covid-19 into the community resulted in a second nationwide lockdown. This lockdown came with much less warning, with the government announcing at 6pm on 17 August that the whole of New Zealand would be moving from Alert Level 1 to Alert Level 4 at 11:59pm that same evening.

Since Covid-19 came to New Zealand, schools have worked with students in new ways to deliver education, including online learning, physical learning packs, and catch-up lessons when back in school. Teachers and principals innovated ways of keeping their students engaged and have often gone above and beyond to support their students. They have responded to the challenges of remote learning and reintroducing students back into the classroom. In doing so, they have supported students and their whānau with concerns about learning progress, attendance, and Covid-19 related anxiety.

The disruptions due to Covid-19 continue to affect many different aspects of education. Teachers and principals have had to navigate an unfamiliar set of challenges, take on new responsibilities and solve complex and high-stakes problems on-the-go as the situation unfolds around them. This has had a significant impact on their wellbeing and workload.

Covid-19 is likely to continue to disrupt school operations. It is essential that schools, and the system supporting them, are prepared for and responsive to changes. This report aims to help with this by understanding the impact on teachers and principals.

About this report

ERO has undertaken this research to understand what the impact of Covid-19 has been on teachers and principals. We also investigated what new practices teachers and principals have put in place in response to Covid-19 and the challenges they expect to face in future as we learn to live with Covid-19 in the community.

Learning in a Covid-19 World

This report looks at the ongoing impact of Covid-19 on teachers and principals. It is part of ERO’s Learning in a Covid-19 World series of reports on English-medium schools. This series includes:

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Schools

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Primary School Students as They Return to the Classroom

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Secondary School Students as They Return to the Classroom

ERO has also published Te kahu Whakahaumaru – Ngā mahi a te rangai mātauranga Māori, which focused on the impact on students in Māori-medium early learning services and schools.

An additional report will be published in 2022 focusing on Māori-medium education and English‑medium schools with high proportions of Māori students, and work is underway on a research report on the impact of Covid-19 on Pacific students and their communities.

This report

For this report, ERO has focused on the experiences and practices of teachers and principals who have been tasked with supporting student learning and engagement in challenging circumstances.

This report is divided into five parts.

Part 1 focuses on the impact of Covid-19 on teachers’ and principals’ wellbeing.

Part 2 focuses on the impact of Covid-19 on teachers’ and principals’ workload.

Part 3 focuses on the impact of Covid-19 in Auckland.

Part 4 reports on how teaching practice has adapted in response to Covid-19.

Part 5 considers the challenges of Covid-19 in the future.

ERO is very grateful for the time of all those who we surveyed and interviewed while conducting our research for this report. We would like to thank all the participating students, teachers, and principals for generously sharing their experiences and challenges around dealing with the impacts of Covid-19. Your contribution enables us to shine a light on shared experiences of challenge and success, and to provide advice and support as we look ahead to an uncertain future.

This reporting is based on:

- surveys of 1,777 principals, 694 teachers, and 10,106 students, in 2020

- surveys of 1,222 principals, 427 teachers, and 2,561 students conducted in June and July 2021

- semi structured interviews with 27 school leaders between September and October 2021.

Further details on data collection and analysis are given in Appendix 1.

Part 1: The impact on wellbeing

Principals and teachers have innovated quickly in response to Covid-19, but their wellbeing has been significantly impacted. Enjoyment of work has declined, and principals and teachers are feeling less supported. Principals of smaller schools, and younger teachers were struggling the most. This section sets out in more detail how teacher and principal wellbeing has been impacted.

Teachers’ and principals’ enjoyment of work has declined

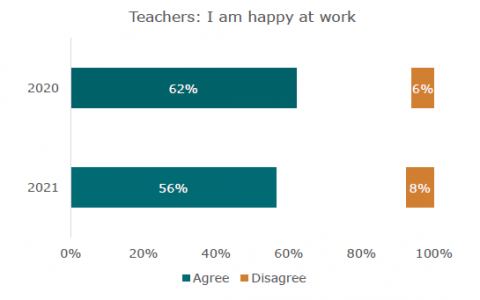

In June and July 2021, just over half (56 percent) of teachers reported that they were happy at work, a decline from about two thirds (62 percent) in September 2020. More than a quarter of principals (27 percent) reported that staff wellbeing had not returned to where it was before the Covid-19 disruptions.

Figure 1: Teachers’ enjoyment of work has declined since September 2020

This figure shows a bar graph. The main title reads "I am happy at work". The graph shows that in 2020, 62% of teachers agreed with the main title statement and 6% disagreed. It also shows that in 2021, 56% of teachers agreed with the main title statement and 8% disagreed.

Principal wellbeing has also declined. Sixty-four percent of principals reported that they were happy at work in June and July 2021, a decline from 68 percent in September 2020.

During the most recent lockdown, we heard from principals that they and their teachers are finding things even more challenging. Principals and teachers are experiencing increased health anxiety around the Delta variant, along with greater exhaustion, apathy, and stress. Uncertainty around how long the lockdown would last was reported to have impacted negatively on wellbeing. Teachers with young families have found this lockdown particularly difficult and stressful, along with those who live alone.

Teachers’ and principals’ life satisfaction is also low, with only 57 percent of teachers and 62 percent of principals reporting that they were satisfied with their life in June and July 2021. This compares poorly with the overall population, with 86 percent of New Zealanders rating their life satisfaction highly in a survey for Stats New Zealand.

Younger teachers and principals of smaller schools were struggling the most

Younger teachers were finding things more difficult than older teachers. In June and July 2021, the youngest teachers (18-35 years old) were twice as likely to say they were not happy at work than those 36-45 years old, and three times as likely as those aged over 46 years old.

“I also have a very young staff, 3 out of my 4 teachers are beginning teachers. They are not equipped to deal with the emotional and social problems that some of our students exhibit.”

Principals of smaller schools were also significantly less happy at work than principals of schools with higher roll sizes. Only 57 percent of principals in small schools were happy at work compared to 72 percent of principals in very large schools. This may be due to lack of other senior leaders to support them. Across all schools, principals who felt well supported by and connected to their leadership team, and who reported that their workload was manageable, were more likely to say they were happy at work.

“Being a teaching principal during lockdown meant as usual, I was wearing many hats. I had a daily online presence, I had my role as principal to fulfil, and I was trying to assist my own child with her learning.”

Teachers and principals were feeling less supported at work

The ongoing disruptions from Covid-19 have impacted on how supported and connected teachers and principals feel. While support and connection was strong in September 2020, by June 2021 it had started to decline.

Teachers

Teachers were feeling less supported by their school. In June and July this year, just over half (56 percent) of teachers agreed that their school had supported their wellbeing over the past week, a decline from 63 percent in September 2020. Teachers were also feeling less supported by and connected to their teaching team.

Principals

Principals were also feeling less supported and connected to their leadership teams – reducing from 87 percent feeling supported and connected in September 2020 to 79 percent in June and July 2021. Some principals reported feeling isolated and struggling to focus on their own wellbeing while taking care of others.

“I feel like there is a huge responsibility on principals to ensure everyone in the school has good and supported wellbeing… As a beginning principal (7 weeks in when we went in lockdown) there wasn't a lot in place to ensure my wellbeing was looked after.”

“Tangible/deliberate support for the Principals wellbeing is often overlooked in a school - we are busy caring for others, not often is this reciprocated in a tangible way.”

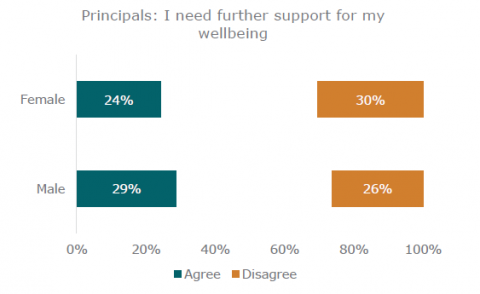

Concerningly, in June and July 2021 over a quarter (26 percent) of principals reported that they needed further support for their wellbeing. Male principals were somewhat more likely to say they needed further support.

Figure 2: Male principals needed further support in June and July 2021

This is a bar graph. The main title reads "I need further support for my wellbeing". The graph shows that 24% of female principals agreed with this and 30% disagreed. It also shows that 29% of male principals agreed and 26% disagreed.

The principals who wanted further support for their wellbeing in June and July 2021 were more likely to find that their workload was unmanageable and feel that their schools had not recovered from the disruptions of Covid-19 and the first lockdown.

Some principals reported that having someone outside the school to talk to could be a valuable support.

“Opportunities to speak with other principals - the stresses and strains can be put into perspective and good ideas shared when meeting with other principals or advisors.”

“I feel very fortunate to have a great support team. However, I am looking at supervision for myself as from next term, just to help me process things well. I think it would be an advantage for all principals to have this as an encouraged option, given all we deal with on a daily basis”

Summary

Both teachers and principals reported negative impacts on their wellbeing as a result of Covid-19 disruptions. Younger teachers and principals of smaller schools are more affected. This was evident in 2020 and has increased since. Teachers and principals were feeling less supported and connected at work, and around a quarter of principals overall reported that they needed more support for their wellbeing.

Part 2: The impact on workload

Principal and teacher workload has increased with Covid-19 disruptions. Teachers and principals have had to take on new responsibilities, deal with new challenging situations, and provide support to students, whānau, and the community. This section sets out what teachers and principals told us about how Covid-19 has impacted on their workload, the impact of staff vacancies, and their concerns about students.

Teachers and principals are increasingly concerned about their workload

Covid-19 disruptions have led teachers and principals to go above and beyond to support their students, but this has led to increased workload for teachers and principals, and has endured beyond lockdowns. In June and July 2021, only a third of teachers (32 percent) and a fifth of principals (19 percent) felt their workload was manageable. This had worsened from September 2020 when 42 percent of teachers and 26 percent of principals felt their workload was manageable.

In lockdown

In lockdowns, teachers’ and principals’ workloads included planning for online delivery and spending time creating or adapting learning packs to be suitable to the specific learning levels of their students. Principals had challenges managing divergent expectations from families and differentiating their teaching and learning programmes to meet students’ needs. In 2021, principals found planning particularly challenging due to the uncertainty around lockdown duration and the speed with which the country went into Alert Level 4.

We also heard that part of the challenge for principals was that they had to play many roles at once. They commented that they sometimes had to play the role of a social worker, were out delivering devices to students, and even caretaking for the school. For example, we heard one story of the school caretaker not being able to get to school due to living on the other side of an Alert Level boundary, and the principal was out mowing the school lawns themselves.

Out of lockdown

Covid-19 has had an ongoing impact on workloads outside lockdowns as teachers and principals reintroduce students back into the classroom, address learning progress, tackle attendance issues and re-engagement, and support students’ Covid-19 related anxiety

“It almost seems that we all went 'hard' during lockdown and afterwards to ensure that students didn't fall behind that we ended up exhausted by the end of the year - teachers, students alike.”

“I need to take more control of my work life balance, currently working 60+ hours per week is unstainable.”

Younger and female teachers and principals have found their workload least manageable during the Covid-19 pandemic

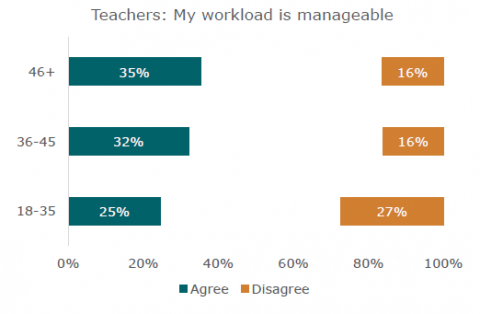

Younger teachers have struggled with their workload more than their older colleagues. A third (35 percent) of teachers aged 46 and above agreed that their workload was manageable, while only a quarter (25 percent) of 18-35 year old teachers agreed.

Figure 3: Younger teachers struggled more with workload

This is a bar graph. The main title reads "Teachers: My workload is manageable". The graph shows that 35% of teachers over 46 agree with this statement and 16% disagree. It shows that 32% of teachers aged 36 to 45 agree that their workload is manageable and 16% disagree. It shows that 25% of teachers aged 18 to 35 agree with the main title statement and 27% disagree.

Younger principals also found their workload most challenging, with four in 10 younger principals (26-45 years) reporting that their workload was unmanageable, compared to three in 10 of principals who were over 56.

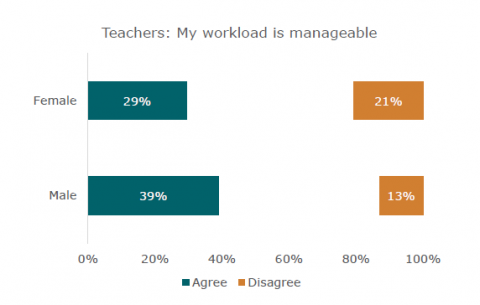

Female teachers were less likely than male teachers to feel their workload was manageable. Three in 10 female teachers agreed that their workload was manageable, while four in 10 male teachers agreed. Female principals also struggled with their workload more than male principals. Only 17 percent of female principals reported that their workload was manageable compared to 23 percent of male principals.

Figure 4: Female teachers found their workload less manageable

This is a bar graph where the main title reads "Teachers: My workload is manageable". The graph shows that 29% of female teachers agreed and 21% disagreed. It shows that 39% of male teachers agreed and 13% agreed.

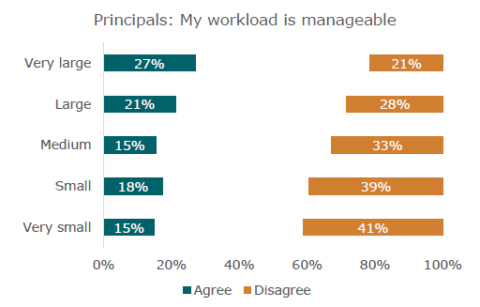

Principals of smaller schools have found their workload less manageable

We found in June and July 2021, that some principals were struggling with their workload more than others. Principals of smaller schools felt their workload was less manageable. Principals of very small schools were nearly twice as likely to report that their workload was unmanageable compared to principals of very large schools.

“As a rural Teaching Principal, there is too much work to be done in the expected timeframe”

Figure 5: Principals of smaller schools found their workload less manageable

This is a bar graph where the title reads "Principals: During 2021, my school has been able to fill all vacancies with suitable applicants". The graph shows that 27% of principals in very large schools agreed with this statement and 21% disagreed. The graph shows that 21% of principals in large schools agreed with this statement and 28% disagreed. The graph shows that 15% of principals in medium schools agreed with this statement and 33% disagreed. The graph shows that 18% of principals in small schools agreed with this statement and 39% disagreed. The graph shows that 15% of principals in very small schools agreed with this statement and 41% disagreed.

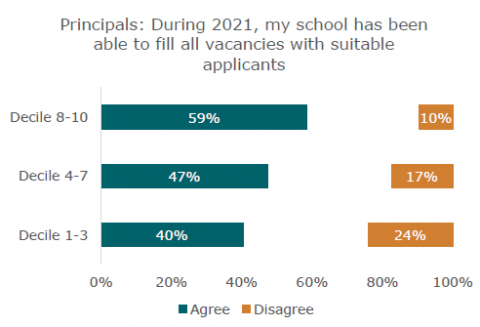

Lower decile and secondary schools have struggled to fill vacancies, impacting on workload

Principals who felt their workload was not manageable were also more likely to be struggling to fill vacancies with suitable applicants.

We found in June and July 2021 that filling vacancies has been challenging for some schools, with 17 percent of principals reporting that they had been unable to fill vacant positions. Things have been particularly challenging for low decile schools, with more than twice as many low decile school principals finding it hard to fill vacancies than high decile school principals.

Figure 6: Lower decile schools had more trouble filling vacancies

Bar graph with main title reading "Principals: During 2021, my school has been able to fill all vacancies with suitable applicants". The graph shows that 59% of principals from Decile 8 to 10 schools agreed with this statement and 10% disagree. The graph shows that 47% of principals from Decile 4 to 7 schools agreed with this statement and 17% disagree. The graph shows that 40% of principals from Decile 1 to 3 schools agreed with this statement and 24% disagree.

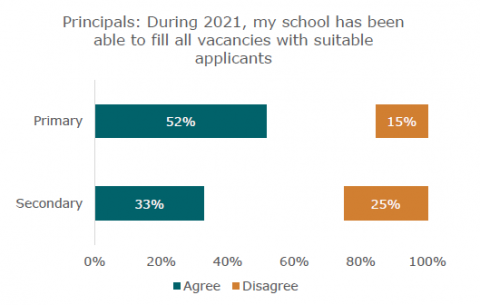

We also saw that principals of secondary schools had a more challenging time filling vacancies than primary school principals. Only a third of secondary school principals agreed they had been able to fill vacancies, compared to over half of primary school principals.

Interviews undertaken in September and October 2021 suggest that staffing remains an ongoing concern for some principals.

Figure 7: Secondary schools had more trouble filling vacancies

Bar graph with the main title "Principals: During 2021, my school has been able to fill all vacancies with suitable applicants". The graph shows that 52% of principals of primary schools agreed with this statement and 15% disagreed. The graph shows that 33% of principals of secondary schools agreed with this statement and 25% disagreed.

Teachers and principals were increasingly concerned about students’ behaviour, engagement, and learning

In response to Covid-19, teachers and principals have adopted many new approaches to meet their students’ learning, engagement, and behaviour needs. However, increasing issues with students’ learning, engagement, and behaviour due to Covid-19 are impacting on teachers’ and principals’ workloads.

Behaviour

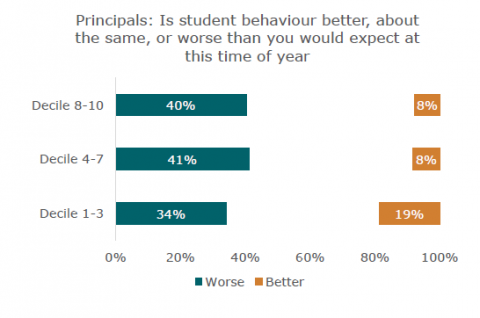

Worryingly, in June and July 2021, 30 percent of teachers and 39 percent principals reported that student behaviour was worse than they would have expected for that time of the year. This was particularly the case for principals for higher decile schools, with 40 percent of high decile schools noting behaviour was worse than expected for this time of the year (compared to 34 percent of low decile school principals). Low decile school principals were twice as likely to report that behaviour was better than expected than high decile school principals (19 percent compared to 8 percent).

“Year 11 students [are] struggling with taking exams seriously and less likely to do what they need to independently. They are wanting to be spoon-fed work rather than thinking for themselves. They are struggling knowing how to study and even forgetting to put hands up to answer questions as they are not used to being in class. Behaviour has deteriorated.”

Principals who reported that their school was still being impacted by Covid-19 disruptions were more likely to report behaviour as having been worse than expected.

“Our biggest concern is student wellbeing, health and welfare, disruption to families and children displaying physical anger toward others and lack of social interactive skills for their age.”

“The New Entrants who came into school following lockdown caused huge issues for us - the lack of 'school readiness', not being able to sit for a story and the violent behaviour is something we have never seen en masse.”

Figure 8: Concern about student behaviour was relatively higher in mid and high decile schools

Bar graph with main title that reads "Principals: Is student behaviour better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year". The graph shows that 40% of principals in Decile 8 to 10 schools think worse, and 8% think better. The graph shows that 41% of principals in Decile 4 to 7 schools think worse, and 8% think better. The graph shows that 34% of principals in Decile 1 to 3 schools think worse, and 19% think better.

Engagement

Engagement has also suffered as a result of Covid-19 disruptions. A fifth of teachers (22 percent) and principals (21 percent) reported in June and July 2021 that student engagement was worse than they would have expected for that time of the year.

During the most recent lockdown we heard that new entrant and Year 2 students have been heavily impacted as their whole school experience has been disrupted by Covid-19. A principal of an intermediate school likewise related that their Year 8 students had experienced a level of disruption for both years they were at the school, leading to concerning levels of disengagement.

Learning

Engagement and behaviour impact on learning. A quarter of teachers (23 percent) and principals (27 percent) reported in June and July 2021 that student learning was worse than they would have expected for that time of the year.

Summary

Covid-19 has led teachers and principals to innovate and adopt new approaches, but it has also increased work pressures. Manageability of workload is an increasing concern for teachers and principals. Younger and female teachers and principals, and principals of smaller schools have been particularly affected. Difficulty filling staff vacancies contributes to workload pressure, especially for secondary and low-decile schools. Responding to the impacts of Covid-19 on student behaviour, engagement, and learning has created additional workload pressures.

Part 3: The impact in Auckland

Auckland has had more disruptions due to Covid-19 than any other region in New Zealand. Even prior to the most recent lockdown, Auckland schools were having a harder time. This has impacted on teachers and principals.

School communities in Auckland have been impacted more

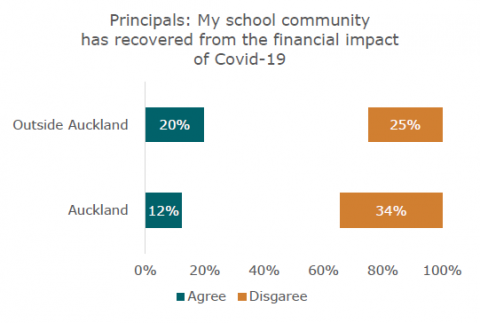

In June and July 2021, over a third (34 percent) of principals in Auckland disagreed that their school community had recovered from the financial impact of Covid-19. This compares to only quarter (25 percent) of principals in the rest of New Zealand.

Figure 9: Auckland communities had recovered less well than others

Bar graph with the main title reading "Principals: My school community has recovered from the financial impact of Covid-19". The graph shows that 20% of principals outside Auckland agreed with this statement, and 25% disagreed. The graph shows that 12% of Auckland principals agreed, and 34% disagreed.

Entering lockdown again in August 2021, Auckland and Northland principals we spoke to expressed ongoing concerns about the impact on their communities. Many students were working to support their families, which took time away from learning.

Schools in Auckland have been slower to recover from disruptions

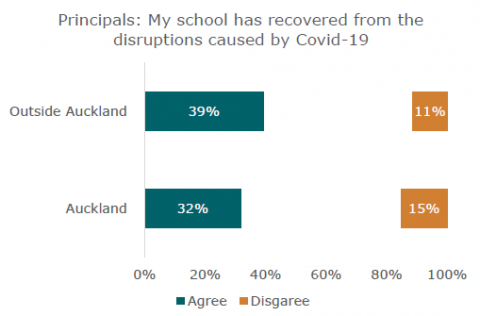

In June and July 2021 (prior to the most recent lockdown), principals in Auckland were less likely to report their school had recovered from Covid-19 disruptions than schools in the rest of the country.

Figure 10: Auckland schools had recovered less well than others

Bar graph with the main title reading "Principals: My school has recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19". The graph shows that 39% of principals outside of Auckland agreed with this and 11% disagreed. The graph shows that 32% of Auckland principals agreed, and 15% disagreed.

The most recent lockdown is likely to have increased the differences between Auckland schools and schools in regions who have not experienced prolonged lockdowns. Principals reported being aware of anxiety from both staff and students about safety when returning to onsite learning, with ongoing active community transmission.

Teachers in Auckland have been impacted more

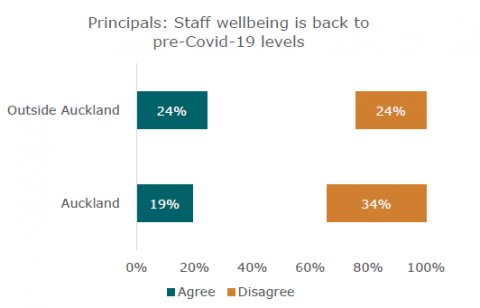

The extra disruptions in Auckland have impacted on teachers’ wellbeing. In June and July 2021, principals in Auckland were more likely to report that staff wellbeing had not returned to the levels they had prior to the Covid-19 disruptions. During the most recent lockdown, principals have reported teachers experiencing fatigue as the lockdown continued.

Figure 11: Staff wellbeing had recovered less well in Auckland

Bar graph with a main title that reads "Principals: Staff wellbeing is back to pre Covid-19 levels". The graph shows that 24% of principals outside of Auckland agree with this and 24% disagree. The graph shows that 19% of Auckland principals agree and 34% disagree.

Māori and Pacific students are more likely to be in schools that have been most affected

There are higher proportions of Pacific students in Auckland. For Pacific students this means their schools, on average, have experienced a much greater disruption and Pacific students are more likely to be in schools that are struggling due to the impact of Covid-19.

For Māori students, many are in Auckland schools (22 percent of all Māori students are in Auckland) disproportionately impacted by Covid-19. In addition, Māori students are more likely to be in smaller schools across the country and these are schools where principals are struggling more with both workload and wellbeing.

Summary

Covid-19 has not impacted all regions equally. Auckland has experienced more disruption than any other area, impacting on Auckland teachers’ and principals’ wellbeing as well as learner engagement and wellbeing. Looking forward to 2022, it will be particularly important to support Auckland schools to meet ongoing challenges.

Part 4: How teaching and learning has changed in response to Covid-19

Covid-19 has meant teachers have had to move quickly to adapt their ways of teaching to keep up with the changing situation. Schools innovated in response to the disruptions in 2020 and some of these changes to teaching practice have endured. In this section, we report on the adjustments to school practice.

Schools adjusted their practices in response to disruptions in 2020

Schools have been committed to meeting the needs of their students throughout the pandemic and have shifted teaching practices in response. ERO research found that, in 2020, the three most common shifts in teaching practice in response to Covid-19 were:

- increased whānau engagement in their children’s learning

- more student agency and self-directed learning

- increased use of digital technology for teaching and learning.

Increased whānau engagement

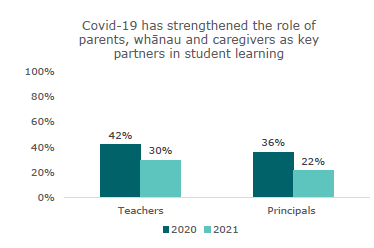

In September 2020, 42 percent of teachers and 36 percent of principals reported increased whānau engagement. In June and July 2021, for 30 percent of teachers and 22 percent of principals there remained a strengthened role of parents, whānau, and caregivers in student learning.

Figure 12: Increased whānau engagement in 2020 and 2021

Bar graph with a main title that reads "Covid-19 has strengthened the role of parents, whānau and caregivers as key partners in student learning". The graph shows that in 2020, 43% of teachers agreed and 36% of principals agreed. The graph shows that in 2021, 30% of teachers agreed and 22% of principals agreed.

Principals reported that these established relationships meant principals and teachers were more easily able to get back up and running with distance learning when needed.

Increased student agency

In 2020 ERO found that, for some students (especially younger students), learning from home in the first lockdown had made them better learners. Teachers and principals reported that student agency was something they wanted to further develop and maintain. However, hoped-for improvements in student agency and self-direction of learning do not seem to have been realised. In June and July 2021, only 15 percent of teachers reported that their students were more able to direct their own learning since learning from home in 2020. This may be because teachers have prioritised focusing on actions to enable students to get back on track with their learning.

Use of digital technology

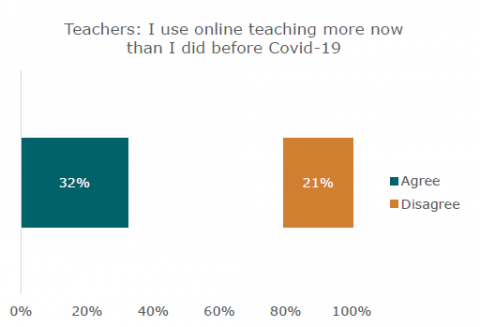

The use of digital technology has been the most enduring change to how schools teach. In June and July 2021 (during onsite schooling), a third (32 percent) of teachers reported that they made more use of online teaching than before Covid-19. This increased to 38 percent for low decile schools who experienced the greatest relative uptake of online teaching methods. Increased use of digital technology also supported schools to re-establish online learning when required for lockdown. This increased confidence in use of digital technology will serve schools well as they continue to respond to Covid-19 in 2022.

Figure 13: A third of teachers reported making more use of online teaching in June and July 2021

A bar graph with a main title that reads "Teachers: I use online teaching more now than I did before Covid-19". The graph shows that 32% of teachers agreed with this and 21% disagreed.

New innovations

In 2021, principals reported that they were continuing to innovate in response to the ongoing disruptions of Covid-19. Two key approaches that have emerged are:

- re-thinking how lessons are organised to increase engagement and learning, for example:

- beginning classes later in the day for senior students

- re-arranging the timetable to focus on one learning area in depth per day.

- continuing to innovate the use of technology to support learning and engagement, for example:

- recording lessons for students (and whānau) to revisit as they had time

- weekly whole school assemblies through online video to maintain connectedness.

This ongoing ability to innovate will be key to responding to the next phase of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Summary

Disruptions from Covid-19 have required teachers and principals to innovate. The increased use of digital technology has been the most enduring change and greater whānau engagement has persisted for a third of teachers and a quarter of principals. As the challenges of Covid-19 have changed, teachers and principals have continued to try new approaches.

Part 5: Looking forward

Looking forward, Covid-19 will continue to challenge principals and teachers and disrupt education. The nature of this impact is changing. It is likely that hybrid learning (both teaching online and in the classroom) will be widespread, staff absences will increase, and there will challenges with student engagement, attendance, and learning. New teaching practices can help meet these challenges, but teachers and principals will need support. In this section we set out the challenges and positive responses.

Future challenges

Covid-19 will continue to impact schools going forward. Whilst the impact remains uncertain, international experience suggests that it is likely to lead to schools having to adjust to the following:

- Hybrid/blended learning – needing to teach both students who are learning from home for short or extended periods while others are learning in the classroom. Maintaining hybrid onsite and online learning programmes is often more intensive for teachers and principals than either entirely onsite or entirely online learning.

- Short but sudden school closures – needing to be fluent at switching to remote learning and then back into the classroom at short notice.

- Staff absences – needing to be able to respond to high levels of staff absences due to both illness with Covid-19 and isolation due to contact with Covid-19. Finally, staff availability may be a concern. In the UK, some evidence suggests that the rate of staff absences has increased significantly as a result of exposure to, or infection with, Covid‑19. Schools that are already finding it difficult to fill vacancies, particularly secondary and low decile schools, are likely to find this particularly challenging.

- Student engagement, behaviour, and attendance challenges – having to re-engage and reintegrate into the classroom students who have had spells learning from home. Experience in New Zealand to date is that after each disruption it takes time for attendance and engagement to return. Disruption to onsite schooling can also have an impact on behaviour once back in the classroom. Even months on from the first nationwide lockdown, nearly half of schools were reporting they had ongoing concerns about attendance.

- Student anxiety – teaching students with higher levels of anxiety which can impact on their behaviour and learning. Last year student anxiety about Covid-19 increased on return to the classroom, with only 58 percent of students feeling safe from Covid-19 once they returned to school. Principals also told ERO that they were concerned about students having higher levels of anxiety about Covid-19 when returning to school. International evidence shows that the incidence of anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents has doubled compared with pre-pandemic estimates. Separation anxiety has also been observed in younger children as they return to school having spent so much time with their parents during lockdowns.

- Learning gaps – disrupted learning leading to both individual students having learning gaps and increased variation in the levels of learning within classes. Some students have been less able to learn remotely. In June and July 2021, NCEA students were least confident they could learn from home. Māori and Pacific students and students in low decile schools were most likely to not have access to a digital device or to be unsure if they would have access to one. Over the last 18 months of disruption there may be a cumulative impact, particularly for students less able to learn remotely or with caring responsibilities including those who have taken jobs to support their families. Internationally, evidence of some groups of students being more severely impacted is beginning to emerge (see for instance: Covid-19 and Education: The Lingering Effects of Unfinished Learning).

Teaching practices that can help

Schools are already innovating to develop practices that can help meet the challenges of this new reality. Detailed examples of practices that can help are available in ERO’s recent reports: Supporting Primary Students as they Return to the Classroom, Supporting Secondary Students as They Return to the Classroom, and Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Secondary School Engagement.

To be best positioned to meet the likely Covid-19 challenges of 2022, schools may want to prepare for the following:

Hybrid/blended learning through:

- ensuring teachers are prepared for a hybrid model, being clear about how it will work and who will lead online learning and in the classroom learning

- having consistency and continuity between home learning and learning in the classroom. For example, finding out which online programmes and activities students enjoyed using when learning remotely and integrating these into the classroom programme, or using an online platform for classroom learning so everything is stored in one location regardless of where learning is taking place.

Supporting learning catch up through:

- using formative assessment to find out where students are at with their learning and using differentiated and individualised teaching strategies to help ensure learning is scaffolded from where students are at to where they need to be. Based on their understanding of where students are at, teachers can set clear learning targets, working closely with whānau

- making opportunities for accelerated learning to make students’ year level learning accessible to them. For example, supporting students to catch up on their learning could mean focusing on the core curriculum and peer socialisation skills to ensure they have strong foundations to build on. This will be a balancing act while trying to make learning engaging and fun for all students

- ensuring learners in their early school careers understand key fundamentals such as early literacy and core numeracy concepts. Failing to understand these may compromise their ongoing capacity to access the curriculum.

Based on the current findings and the findings of our previous reports, we are aware students in low decile schools have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Additional resources may be required to support low decile schools who are trying to catch up learners who have experienced greater disruption, and many have larger gaps in learning than those at higher decile schools

Having a plan to support re-engagement both in the classroom and remotely through:

- continuing to build strong relationships with students and their whānau. A quarter of leaders told ERO they found greater whānau involvement and integration of home and school learning a key success during the 2020 lockdown

- monitoring and tracking engagement to identify students at risk of disengaging. For example, intensifying attendance monitoring and using ‘check in’ surveys or ‘pulse checks’

- using positive and consistent messaging about the value of good attendance, communicating about successes, and expressing belief in students’ capabilities

- working effectively with agencies outside school to re-engage students. For example, schools could engage with Whānau Ora navigators.

Supporting students’ wellbeing through:

- focusing on connections and togetherness through a positive school climate for students. For example, breaking the day up into smaller blocks of learning time, allowing students to take more regular breaks, creating opportunities for students to socialise, and providing quiet spaces for students to ‘chill out’

- offering specific support for strengthening social-emotional skills and behaviours. For example, teaching their students ways to strengthen their tolerance, resilience, self-regulation, and ways to cope with anxiety.

Support for teachers and principals

Putting in place new teaching responses to meet the challenges of Covid-19 will take time and effort. This report has found that teachers and principals are struggling. Their enjoyment in their work is low and declining, and concerns about workload are rising. They will need support to meet the ongoing challenges of Covid-19 and adjust to new ways of working. From ERO’s research we have identified four actions that could be taken to support teachers and principals.

- Supporting availability of teachers

Teaching and learning in a Covid-19 world is staffing-intensive. Students require additional support from teachers and providing both online and onsite learning is a new challenge for most New Zealand schools. It is not yet clear that individual teachers can provide both at the same time. Staff absences and vacancies are likely to be significant issues for some schools. Schools should consider contingency plans to deal with staff absences. There may also be opportunities to pool staffing resources across multiple schools, both regionally and nationally.

- Opportunities to share effective approaches

Many aspects of teaching and learning during a pandemic are new and unknown to schools. For example, hybrid learning is new and it is likely schools across the country will be grappling with the challenge of how to make it work. There is a relative lack of established literature on effective practice. Re-engaging students into the classroom from time learning remotely is also an unfamiliar challenge to schools. As schools develop their approaches, being able to share what they have learnt and draw on emerging good practice from New Zealand and abroad will help. Education agencies could help by providing schools with these opportunities.

- Using existing expertise in distance and blended learning

The Ministry of Education provides resources to support online learning through the Virtual Learning Network (VLN). Additionally, Te Kura | Te Aho o te Kura Pounamu (formerly the Correspondence School) has considerable expertise and experience in providing distance learning and hybrid approaches in the New Zealand context. Its distance learning provision can achieve good outcomes and Te Kura’s tailored programmes delivered in response to Covid-19 have been highly successful (see ERO’s previous report: Responding to the Covid-19 crisis: Supporting Auckland NCEA students). Te Kura’s expertise could be used to support all schools as they come to grips with the need for more hybrid/blended learning approaches in 2022.

- Supporting principals’ and teachers’ wellbeing

Many principals reported feeling the pressure and isolation of their roles, and that they valued opportunities through formal or informal networks to support each other and share how they were going. Principals also appreciated when they received acknowledgment from their communities and Boards of Trustees. Kāhui Ako and other school networks already provide these opportunities for some principals, but the continued high levels of isolation principals are reporting suggests action is needed to ensure all principals have the peer support they need. For example, in response to the Christchurch earthquake a group of experienced principals led regularly contacting and supporting their colleagues. In addition to peer networks, some principals and teachers could benefit from access to professional support that helps them navigate the challenges of Covid‑19 in 2022.

Summary

Ongoing disruptions from Covid-19 will require teachers and principals to continue to imaginatively innovate. By anticipating the challenges 2022 is likely to pose and preparing to meet them, schools can be well positioned.

Useful resources for principals and teachers

- Ministry of Education COVID-19 Information and Advice

- Workforce Wellbeing Package

- SPARKLERS resource hub

- Springboard Trust

- NZEI Covid-19 Information

Conclusion

This report has highlighted how teachers and principals have innovated and adapted in response to Covid-19. But it has also revealed the significant and worsening impacts of Covid-19 on teachers’ and principals’ wellbeing and workload. Providing continuity of learning for students through repeated disruptions and supporting student and whānau wellbeing has taken a toll.

Teachers’ and principals’ wellbeing has declined, with particular impacts on younger teachers, and principals of smaller schools. A quarter of principals told us they required more support for their wellbeing. Challenges to wellbeing are clear across the country, but those schools in Auckland that have been more impacted are of especial concern.

Workload has been an increasing concern both during lockdown distance learning and returning to onsite learning, and principals remain concerned about staffing going into 2022. Again, younger teachers and principals of smaller schools reported finding their workload less manageable.

Schools have, and continue to, adjust their practice to meet the challenges of Covid-19. As we move into 2022 further innovation will be required. Teachers and principals will need support to meet these challenges.

Appendix 1: Methodology

ERO used a mixed-method approach of both surveys and short interviews. This report also draws on data collected in 2020 and previously reported in the Learning in a Covid-19 World series.

ERO used a mixed-methods approach across multiple data sources, yielding both quantitative and qualitative data, for this investigation. The target population were all English-medium schools in New Zealand. Data were collected across surveys of principals, teachers, and students and interviews with principals. Surveys were conducted at the end of June 2021 approximately one year on from the Covid-19 disruptions caused by the national lockdown in March 2020 and approximately one month prior to a second nationwide lockdown in August 2021. The interviews were conducted during and after the second national lockdown, while Auckland, Northland and Waikato schools remained at Alert Level 3.

Quantitative data were statistically analysed using STATA, and qualitative data were thematically analysed by an experienced team.

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the unique contribution to wellbeing and workload outcomes of various demographic factors and answers to other survey questions. These have been reported alongside the percentage agreement (strongly agree and agree) and/or percentage disagreement (strongly disagree and disagree) to demonstrate the size of these associations and differences. Where we have reported differences between survey results in 2020 and 2021, these were statistically significant. All significance was tested at p <0.05.

2021 Surveys

ERO conducted surveys through the Ask Your Team platform.

We recruited students and teachers from the nationally representative sample of 67 primary schools and secondary schools we had previously surveyed for the Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Schools report. Of these, 25 schools participated in the current data collection. The pool we recruited from was designed to ensure a mix of schools from different school sizes and decile groups were included. Teachers and students from these schools were invited to participate in a short online survey about their wellbeing and their experiences since lockdown. Responses were collected for three weeks from 23 June to 9 July 2021. We received 2561 responses to the student survey and 427 responses to the teacher survey.

We also invited all principals of English-medium schools in New Zealand to complete a survey about their wellbeing and their experiences since the first national lockdown. Responses were collected between 29 June and 9 July 2021. We received 1,222 responses from principals – a response rate of 53.8 percent.

A full listing of the survey questions we asked can be found in Appendices 2 through 4 at the end of this report. ERO accessed aggregated survey results, without being able to identify individual schools’ responses. Schools were given access to their own survey data to help with their own evaluation and planning. The results from the student and teacher surveys were grouped together to keep individual responses confidential.

2021 Interviews

ERO also conducted 27 interviews with school leaders between September and October 2021, during the most recent lockdown. These were semi-structured interviews around the following broad themes:

- preparedness

- how this lockdown differed from the 2020 lockdown

- support for learning and wellbeing

- successes

- challenges

- ongoing support needed.

2020 Surveys

ERO conducted two rounds of surveys, through the Ask Your Team platform.

For the first round of surveys, we recruited a nationally representative sample of 67 primary and secondary schools and invited teachers and students from these schools to answer a short survey online about their wellbeing and experience of learning and teaching during the lockdown. The sample was designed to ensure a mix of schools from different school sizes and decile groups were selected, and there was a separate survey for students and teachers. Responses were collected for three weeks from 23 April to 13 May, covering the tail end of Alert Level 4 and the beginning of Alert Level 3, when most students were learning from home. We received 10,106 responses to the student survey and 694 responses to the teacher survey.

For the second round of surveys, we invited all principals of English-medium schools in New Zealand to complete an online questionnaire. Responses were collected between 2 September and 16 September 2020. We received 1,777 responses, a response rate of 75.5 percent. We also surveyed teachers and students from the sample of primary and secondary schools again. These responses were collected between 31 August and 15 September 2020, which was a few months after the national lockdown, but only a day after the end of Auckland’s second lockdown. We received 4,666 responses to the student survey and 686 responses to the teacher survey.

ERO accessed aggregated survey results, without being able to identify individual schools’ responses. Schools were given access to their own survey data to help with their own evaluation and planning. The results from the student and teacher surveys were grouped together to keep individual responses confidential.

2020 Interviews

ERO conducted two rounds of phone interviews. The first round of interviews focused largely on schools’ experience of Alert Levels 4 and 3 when most students were learning offsite, while the second round of interviews focused on attendance, re-engagement and student progress and achievement upon the return to onsite schooling.

For the first round of interviews, Review Officers interviewed principals and board chairs in 580 schools. These interviews took place from the middle of June 2020 to early August 2020. For the second round of interviews, Review Officers interviewed principals and a small group of teachers in 160 schools. These interviews took place from late August 2020 to late September 2020.

Review Officers provided written notes on the interviews which were then analysed to develop themes. More detailed analysis was conducted on samples of 144 of the first round schools, and 100 of the second round schools.

2020 Focus Groups

ERO conducted 36 focus groups across New Zealand to gather the perspectives of parents/whānau and more in-depth perspectives from trustees, teachers, and students. These focus groups were conducted from late August to the middle of September 2020. Focus groups took a conversational approach, and ERO staff reported the findings on summary sheets for each key group of informants (parents/whānau, teachers, trustees, and students).

Appendix 2: Student survey questions (2021)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- In the past week I have felt connected to my friends

- At my school, I have an adult who really cares about me

- I have adults I can go to if I need help

- I would be able to learn from home if there was another lockdown

- I would like to learn from home sometimes even if there is not a lockdown

- My teachers care about my learning

- I am enjoying my learning

- I got extra help from my teachers when I returned to school after the Covid-19 lockdowns

- I have been coping with my schoolwork

- My learning progress has been good this term

- In the past week I have been able to keep up with my learning

- I need to catch-up on my learning

- I am feeling safe from Covid-19

- My teachers care about my wellbeing

Multichoice

- Do you have a device at home you could use to learn from home if you needed to?

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- I feel happy

- All the time

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- Never

Open-Response Questions

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us about Covid-19?

Appendix 3: Teacher survey questions (2021)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- My school has supported my wellbeing over the past week

- I feel supported by, and connected with, my teaching team

- Overall, I am satisfied with my life right now

- The things in my life are worthwhile

- I am happy at work

- My workload is manageable

- I am well prepared to respond to any further Covid-19 lockdowns

- I am confident I could continue to support students learning in another lockdown

- Covid-19 has strengthened the role of parents, whānau and caregivers as key partners in student learning

- My students are engaged in their learning

- I use online teaching more now than I did before Covid-19

- I have kept changes to my teaching practice that I made in response to Covid-19

- I have kept curriculum changes I made in response to Covid-19

- My school has continued to prioritise student wellbeing

- My students are more able to direct their own learning since learning from home last year

Multichoice

- Is student learning better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much worse

- Worse

- About the same

- Better

- Much better

- Don’t know

- Is student engagement better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much worse

- Worse

- About the same

- Better

- Much better

- Don’t know

- Is student behaviour better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much worse

- Worse

- About the same

- Better

- Much better

- Don’t know

Open-Response Questions

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us about the impact of Covid-19 on your students?

Appendix 4: Principal survey questions (2021)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- Overall, I am satisfied with my life right now

- I have things in my life that are worthwhile

- I feel supported by, and connected with, my leadership team

- I am happy at work

- My workload is manageable

- Staff wellbeing is back to pre Covid-19 levels

- I need further support for my wellbeing

- I am confident my board will support me and my school should any further lockdowns occur

- I feel well prepared to deal with another lockdown

- Covid-19 has strengthened the role of parents, whānau and caregivers as key partners in student learning

- My school has continued to prioritise student wellbeing

- I am confident that our school community will get vaccinated when it is offered

- During 2021, my school has been able to fill all vacancies with suitable applicants

- My school has recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19

- My school community has recovered from the financial impact of Covid-19

Multichoice

- I feel happy

- All of the time

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- Never

- If there were another lockdown what would be the biggest challenges for your school? If ‘other’, please describe.

- Student access to devices/connectivity

- Student disengagement

- Student wellbeing

- Staff workload

- Staff wellbeing

- Economic issues in the community

- Other (free text)

- Is student learning better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much better,

- Better

- About the same,

- Worse

- Much worse

- Don’t know

- Is student engagement better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much better,

- Better

- About the same,

- Worse

- Much worse

- Don’t know

- Is student behaviour better, about the same, or worse than you would expect at this time of year?

- Much better

- Better

- About the same

- Worse

- Much worse

- Don’t know

- What is your biggest concern about your school right now? If other, please describe.

- My staff’s wellbeing

- My staff’s workload

- Student attendance

- Student learning and achievement

- Student wellbeing

Appendix 5: Student survey questions (2020)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- In the past week, I have felt connected to my friends

- At my school, I have an adult who really cares about me

- I have adults I can go to if I need help

- Learning from home has made me a better learner

- There is someone in my home who can help me with my learning

- In my home, there has been a parent or another adult who has become more interested in my learning this term

- In the past week, I have been able to do the things I enjoy at school

- My teachers care about my learning

- I am enjoying my learning

- I have been coping with my schoolwork

- My learning progress has been good this term

- In the past week, I have been able to keep up with my learning

- I feel I am up to date with my learning

- My teachers care about my wellbeing

- My teachers have given me extra help with my learning when I needed it

- I am feeling safe from Covid-19

- I am feeling positive about the rest of the year

- The people in my home are doing well

Multi-Choice Questions

- What more support do you need from your teachers? If you choose "Anything else", there is a text box for you to let us know what you need

- None, I am okay

- Anything else

- Help with my learning and wellbeing

- Help with my wellbeing

- Help with my learning

- I feel happy

- Never

- Some of the time

- Most of the time

- All the time

Open-Response Questions

- What is the main thing you liked about learning from home?

- Is there anything else you would like to say?

Appendix 6: Teacher survey questions (2020)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- My school has supported my wellbeing over the past week

- My school leaders have helped resolve challenges related to student wellbeing during Covid-19

- My school leaders have helped resolve challenges related to student learning during Covid-19

- The Covid-19 response has strengthened our ties with the community

- At my school, teachers have worked together to support students during Covid-19

- I feel supported by, and connected with, my teaching team

- My school has responded effectively to Covid-19

- Our Board has effectively supported the school to respond to Covid-19

- My school has actively gathered feedback from students on how to support them during Covid-19

- My school has actively gathered feedback from our parents, whānau and caregivers on how to support students during Covid-19

- The Covid-19 response has strengthened the role of parents, whānau and caregivers as key partners in students’ learning

- I am confident I can support my students’ wellbeing needs during Covid-19

- My students are engaged in their learning

- I am confident that my students will be able to catch up with their learning

- I am confident I can support my students’ learning needs during Covid-19

- I have discussed student progress with my students during Covid-19

- I have discussed student progress with parents, whānau and caregivers when needed during Covid-19

- I regularly discuss my student’s progress with my teaching team

- I have reviewed the learning goals for all my students during Covid-19

- Students at risk of not achieving are receiving targeted support or intervention

- Overall, I am satisfied with my life right now

- The things in my life are worthwhile

- The people I live with are doing well

- I am happy at work

- I am feeling positive about the rest of the year

- My workload is manageable

Multi-Choice Questions

- My relationship with my students has improved during Covid-19

- No

- About the same

- Yes

- My relationships with parents, whānau and caregivers has improved during Covid-19

- No

- About the same

- Yes

- I feel happy

- Never

- Some of the time

- Most of the time

- All the time

- What is your biggest concern right now?

- The wellbeing of others I live with

- Lack of social interaction

- My financial situation

- My physical health

- Exposure to Covid-19

- My mental wellbeing

- Supporting my students’ learning

- Other

Open-Response Questions

- What has been most helpful in supporting your students during Covid-19?

- What else do you need to support your students’ learning?

- What do you see as your biggest teaching challenge for the rest of the year?

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us?

Appendix 7: Principal survey questions (2020)

Agree-Disagree Questions

For these questions, respondents could select from: Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know.

- The Covid-19 response has strengthened the role of parents and whānau as key partners in students’ learning

- Our school has responded effectively to Covid-19

- My school has actively gathered feedback from students on how to support them during Covid-19

- Our external providers have been able to meet our needs during Covid-19

- Our school has been able to support our students’ learning during Covid-19

- My school has actively gathered feedback from our parents, whānau and caregivers on how to support students during Covid-19

- Overall, I am satisfied with my life right now

- I have things in my life that are worthwhile

- The people I live with are doing well

- I have had someone I can talk to about my work during Covid-19

- The Covid-19 response has strengthened our ties with the community

- Our school leaders have worked well together to support students during Covid-19

- I feel supported by, and connected with, my leadership team

- I am happy at work

- I am feeling positive about the rest of the school year

- My workload is manageable

- My workload has reduced since term 2

- My Board has supported my wellbeing during Covid-19

- I have received the support I need from my Board to support student wellbeing during Covid-19

- Our Board has supported the school effectively during the Covid-19 pandemic

- My school has been reviewing learning goals for all students during Covid-19

- Students at risk of not achieving are receiving targeted support or intervention

- I am confident my students will be able to catch-up with their learning

Multi-Choice Questions

- What has been your biggest challenge supporting your staff during Covid-19? If 'other' please describe

- Other

- Workload

- Financial pressures

- Physical health

- Exhaustion

- Mental wellbeing

- What is your biggest concern about your school right now? If 'other' please describe

- Exposure in our school community to Covid-19

- Student wellbeing

- Student learning and achievement

- Student attendance

- My staff’s workload

- My staff’s wellbeing

- Other

- What is your main concern about your students for the rest of the school year? If 'other' please describe

- Staying engaged at school

- Attendance

- Learning progress

- Wellbeing

- Other

- What is your main concern about your teachers for the rest of the school year? If 'other' please describe

- Workload

- Financial pressures

- Physical health

- Exhaustion

- Other

- What do you see as the biggest challenges for your school for the rest of the year? If 'other' please describe

- Exposure in our school community to Covid-19

- Student wellbeing

- Student learning and achievement

- Student attendance

- Staff workload

- Staff wellbeing

- Other

- I feel happy

- Never

- Some of the time

- Most of the time

- All the time

- What is your biggest concern about yourself right now? If 'other' please describe

- The wellbeing of others I live with

- Lack of social interaction

- My financial situation

- My physical health

- My mental wellbeing

- Other

- What proportion of your students have fallen behind in their learning due to Covid-19?

- Don't know

- 75-100 percent

- 50-75 percent

- 25-50 percent

- Less than 25 percent

Yes-No Questions

- Are there students in your school who you are concerned may not be able to catch-up with their learning due to Covid-19? If 'Yes' please detail what groups of students are you most concerned about in the text box below. (e.g. school year, gender, ethnicity, students with learning needs)

Open-Response Questions

- What further support do you need to support your wellbeing?

- What additional support does your school need to help you support your students’ learning during Covid-19?

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us?

References

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2021). Covid-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-education-the-lingering-effects-of-unfinished-learning

Education Review Office. (2021). Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Primary School Students as They Return to the Classroom. https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/learning-in-a-covid-19-world-supporting-primary-school-students-as-they-return-to-the-classroom

Education Review Office. (2021). Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Secondary School Engagement. https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/learning-in-a-covid-19-world-supporting-secondary-school-engagement

Education Review Office. (2021). Responding to the Covid-19 crisis: Supporting Auckland NCEA students. https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/responding-to-the-covid-19-crisis-supporting-auckland-ncea-students

Miller, C. (n.d.). Back-to-School Anxiety During COVID: How to help kids handle fears and gain independence. https://childmind.org/article/back-to-school-anxiety-during-covid/

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Advice for schools/kura: Information for schools/kura about COVID-19. https://www.education.govt.nz/covid-19/advice-for-schoolskura/

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Workforce Wellbeing Package: COVID-19 Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) Support. https://www.education.govt.nz/covid-19/workforce-wellbeing-package/

NZEI. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) information for NZEI Te Riu Roa members. https://campaigns.nzei.org.nz/covid-19/

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–1150. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Sibieta, L. (2021). COVID-related teacher and pupil absences in England over 2020 autumn term. https://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Teacher-absence-analysis_EPI.pdf

Sparklers. (n.d.) https://sparklers.org.nz/

Spring Board Trust. (n.d.). COVID-19: Resilience: Leading resilience and hauora for your school and community. https://www.springboardtrust.org.nz/covid-19-resilience

Stats NZ. (2019) Slight fall in overall life satisfaction, but most Kiwis still satisfied. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/slight-fall-in-overall-life-satisfaction-but-most-kiwis-still-satisfied