Summary

Since 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused significant disruption to schools, their staff, learners, and whānau. Three years on from the start of the pandemic, this report has found significant and concerning ongoing impacts on learners’ progress, particularly for learners in poorer communities, and on teachers and principals.

Going forward we will need a concerted focus on helping all learners to catch up and provide targeted support to those more impacted by the pandemic. Principals and teachers will need to be supported to enable them to do this, as they continue to experience the impact of Covid-19 on their workloads and wellbeing. Schools in poorer communities will need the most support as they face the biggest learning challenges, have principals whose wellbeing has been more impacted by Covid-19, and are finding it the hardest to recruit teachers.

Whole article:

Long Covid: Ongoing impacts of Covid-19 on schools and learningExecutive Summary

How are learners doing?

Learners’ wellbeing has improved

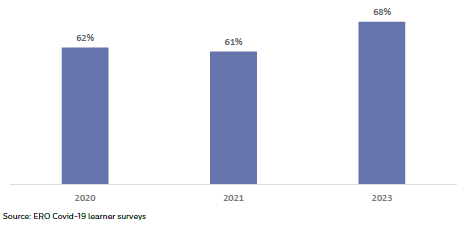

Learners feel happier overall, with more than two thirds (68 percent) of learners reporting they feel happy most or all of the time, an increase from 61 percent in 2021, and 62 percent in 2020.

We found the most important reported driver of happiness at school is being connected to friends. Other drivers of learners’ happiness are feeling safe from Covid-19 and having an adult who cares for them at school.

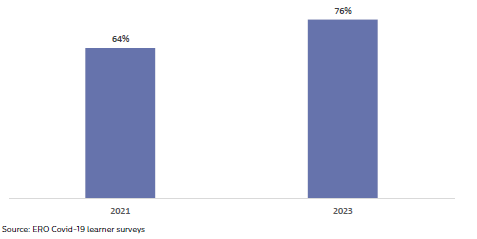

Learners are feeling more connected to their friends. Three quarters of learners (76 percent) report feeling connected to their friends, compared with just under two thirds (64 percent) in 2021 and two thirds (66 percent) in 2020.

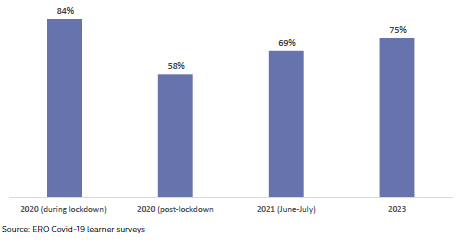

Learners are less worried about Covid-19. Three quarters (75 percent) of learners are now feeling safe from Covid-19, which is up from just over half (58 percent) after lockdown in 2020.

Attendance and behaviour are concerning

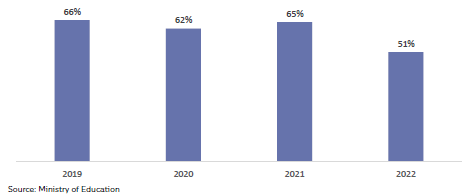

Covid-19 has had a serious impact on attendance. Overall, regular attendance dropped as low as 40 percent in Term 2 of 2022, reflecting high rates of Covid-19‑related absences through illness and isolation. By the end of 2022, regular attendance had only recovered to 51 percent, suggesting Covid-19 disruptions have led to longer term impacts on attendance.

Challenging behaviour remains a significant issue. Four in 10 (41 percent) principals report that behaviour is worse or much worse than they would expect at this time of year, which is not significantly different from 2021 (39 percent).

Learners’ progress and achievement are increasingly impacted

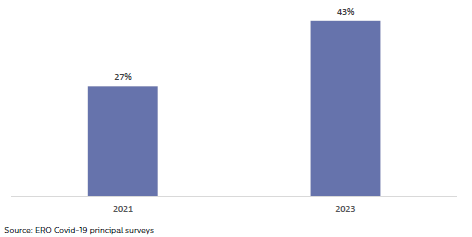

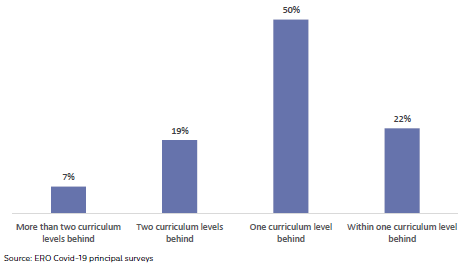

Principals are increasingly concerned about learning, with nearly half (43 percent) of principals saying that learning is worse than they would expect at this time of year, a substantial increase from 27 percent in 2021. A quarter (26 percent) of principals say their struggling learners are two or more curriculum levels behind.

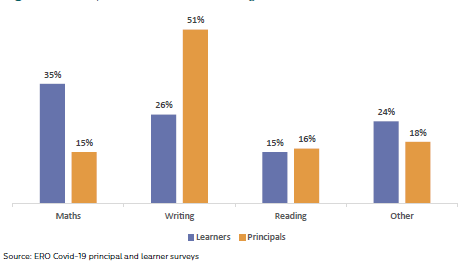

Principals and teachers are most concerned about writing, with half (51 percent) of principals and nearly half (44 percent) of teachers reporting writing as the learning area of biggest concern.

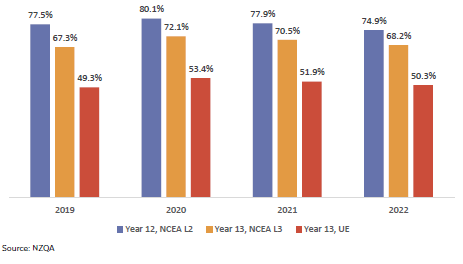

NCEA attainment has fallen. Attainment rates for NCEA Level 2 are below where they were in 2019, before the pandemic. From 2020 to 2022, modifications were made to award additional Learning Recognition Credits. If these were not in place, attainment in 2022 would have been even lower.

Learners in poorer communities have been more impacted

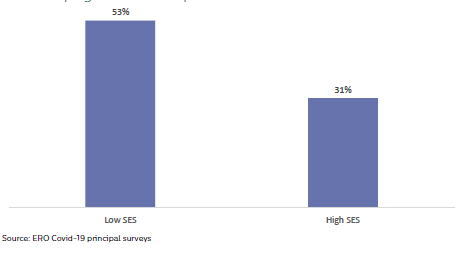

Principals and teachers in schools in poorer communities are much more concerned about their learners’ progress. Over half (53 percent) of principals from schools serving poorer communities say that student learning is worse than expected compared to a third (31 percent) of principals serving schools in better-off communities.

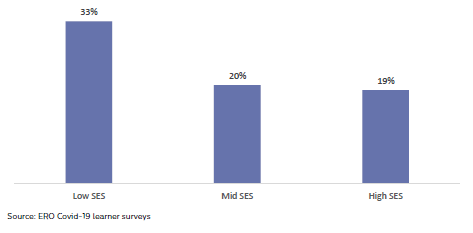

Learners in poorer communities are further behind. Principals in schools serving poorer communities are more than three times as likely as those serving better-off communities to say that their struggling learners are behind by two curriculum levels or more (46 percent compared to 14 percent).

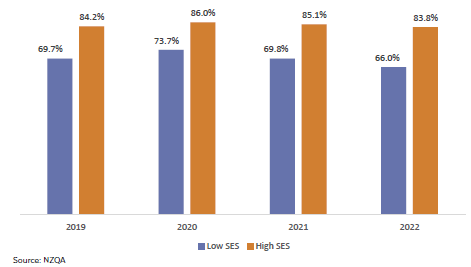

NCEA Level 2 attainment has fallen for learners in poorer communities. The gap between schools in poorer and better-off communities has widened from 14.5 percentage points in 2019 to 17.8 percentage points in 2022.

Māori learners’ progress has been more impacted

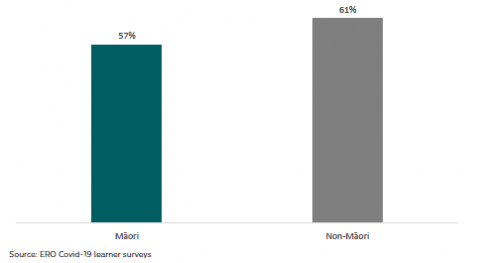

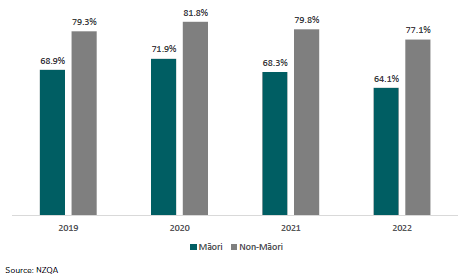

Māori learners are less positive about their learning progress, and NCEA Level 2 outcomes have fallen. Fifty-seven percent of Māori learners say their learning progress has been good this term compared to 61 percent of non-Māori learners, and Māori learners’ NCEA Level 2 attainment has fallen to 64.1 percent in 2022, which is the lowest it has been since 2014. The gap between Māori and non-Māori learners’ NCEA Level 2 attainment has increased from 10.4 percentage points in 2019 to 13 percentage points in 2022.

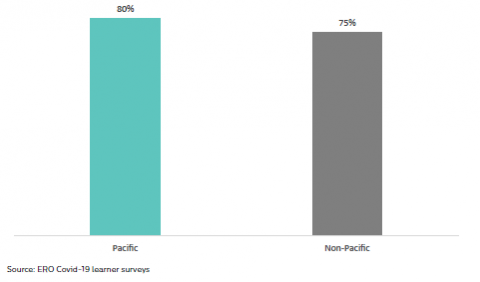

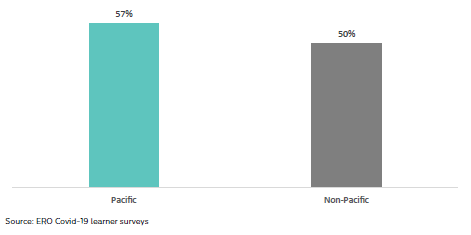

Pacific learners feel more positive, but their learning has been more impacted

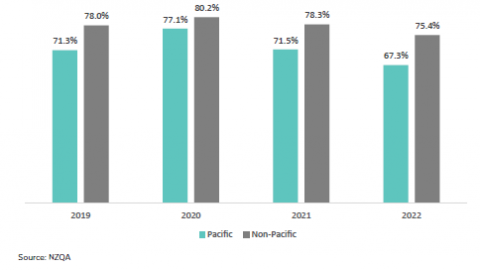

Pacific learners are more likely than others to enjoy their learning, but their NCEA attainment has fallen. Positively, the proportion of Pacific learners enjoying their learning is greater (63 percent) than for non-Pacific learners (52 percent). However, Pacific learners' NCEA Level 2 attainment has fallen to 67.3 percent in 2022 (down from 71.3 percent in 2019) and the gap between Pacific learners and non-Pacific learners has increased (from 6.7 percentage points in 2019 to 8.1 percentage points in 2022).

Learners from ethnic communities face greater wellbeing challenges

Fewer learners from ethnic communities feel cared for by an adult or teacher at school. Only 37 percent of Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African (MELAA) learners and 43 percent of Asian learners report they have an adult at their school who really cares about them compared to 51 percent of all learners. This matters, as we have found that it is a key driver of happiness at school.

Additionally, our data suggests that MELAA learners are less likely than all learners to feel happy most or all of the time. This is consistent with the finding in ERO’s report Education for All Our Children that MELAA learners report lower wellbeing than others.

How are teachers and principals doing?

Covid-19 impacts on schools have accumulated. Only a fifth (19 percent) of principals in 2023 believe their school has recovered from disruptions caused by Covid-19. This compares to 37 percent in 2021.

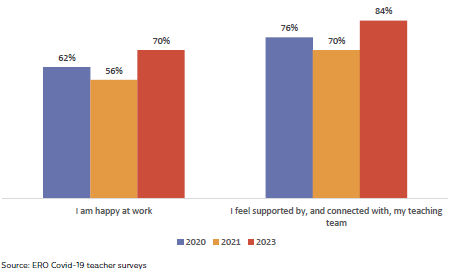

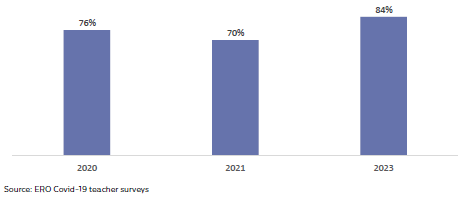

Despite this, there are some indications that teachers’ wellbeing has improved. Teachers we surveyed report being happier at work in 2023 compared to 2020 and 2021, and more connected to their teaching teams. More data would be needed to be confident that this is a real trend.

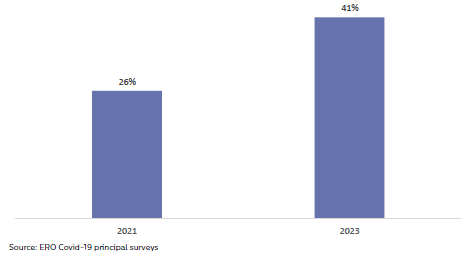

However, increasing numbers of principals need support for their wellbeing. Covid-19 pressures have accumulated and, in 2023, four in 10 (41 percent) principals report needing more support, which is up from 26 percent in 2021. Nearly a third (30 percent) of principals say they had accessed support for their wellbeing in the past year.

The most important reported driver of principals’ happiness is how manageable they are finding their workloads. Other key drivers are feeling connected to, and supported by, their leadership team, and having schools that have recovered from disruptions.

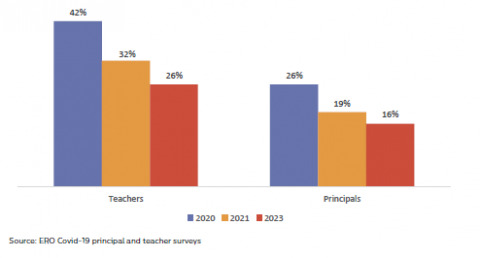

Workload manageability is a concern. As the impact of Covid-19 continues, only a quarter (26 percent) of teachers report their workload as being manageable (down from 42 percent in 2020) and only 16 percent of principals say their workload is manageable (down from 26 percent in 2020).

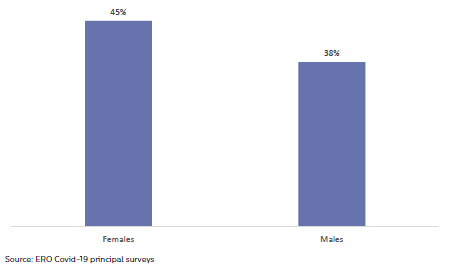

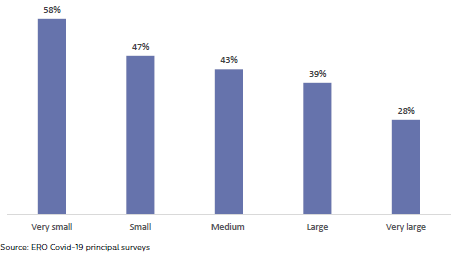

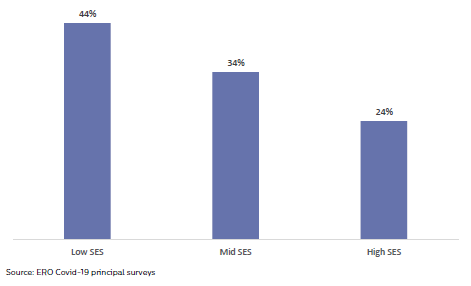

Principals of small schools and female principals are struggling more. We continue to find that the smaller the school, the more principals struggle with their workload. Principals of very small schools (58 percent) were much more likely to find their workload unmanageable compared to principals of very large schools (28 percent). We also found that female principals (45 percent) are more likely to find their workload is unmanageable compared to male principals (38 percent).

Filling vacancies is a concern. Nearly a quarter (23 percent) of principals say they are struggling to fill vacancies in 2023. Principals of schools in poorer communities are finding it particularly difficult (31 percent) compared with those in better-off communities (18 percent).

What do we need to do?

The cumulative impact of the past three years means that education in New Zealand has ‘Long Covid’ – a situation that will not easily bounce back to business as usual, with:

- learning gaps for all learners

- increasing inequities in outcomes

- principals and teachers who are struggling.

If unaddressed, the impact of these issues will continue to be felt over the coming decade as learners make their way through school, and principals and teachers may choose to leave the profession.

To recover from ‘Long Covid’ in education, ERO recommends action in three areas:

- focusing now on making up for lost learning opportunities.

- targeting learning support for those who have been most impacted by the pandemic.

- supporting principals and teachers.

a) Making up for lost learning opportunities

ERO recommends that, in 2023, everyone in education focuses on helping all learners to catch up on the learning they have missed. This means:

- Getting more learners to school every day to maximise their time for learning, for example:

- through schools’ attendance strategies, increasing understanding of the importance of attendance and awareness of how often learners are attending school

- by identifying and tackling specific barriers to attendance.

- Understanding and addressing learning gaps of all learners, for example by:

- being clear where learners should be at in all year levels and subjects and planning early - this includes diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments, identifying barriers to learning, and having plans to tackle those barriers

- prioritising addressing learning gaps in reading, writing, and numeracy, including through the wider curriculum

- monitoring the effectiveness of remedial responses and adapting as necessary.

- Addressing these gaps through accelerating learning, for example by:

- helping learners, parents and whānau understand their own progress through timely, relevant, and tailored feedback

- as the new common practice model is adopted, focusing on using an adaptive teaching approach, recognising that learners learn at different rates and require different forms and levels of support

- providing tailored group and individual acceleration programmes by scaffolding learning to help students who need support so they can continue to progress.

b) Targeting support to those who most need it

ERO recommends that, in 2023, we put in place significant, targeted, and tailored learning support for learners who need it the most. This means:

- Identifying which learners have been most impacted, for example by:

- recognising the particular challenges faced by schools and learners in poorer communities.

- teachers, counselling staff, teacher aides, and other staff working together to assess learner needs – including knowing barriers to learning.

- using school-wide data to make informed decisions. This includes identifying patterns of attendance, academic achievement, behavioural and socio-emotional needs, engagement in school, and interaction with peers.

- Having multi-tiered, targeted, and sufficiently intensive support for learning, for example by:

- providing explicit and systematic instruction – this has been found to be effective in reading, writing, and mathematics

- breaking down content or tasks to enhance clarity, adapting lessons whilst maintaining high expectations for all learners, and making sure learners have opportunities to meet those expectations.

- Connecting and working with their parents and whānau to support learning, for example by:

- increasing engagement of parents and whānau, teachers, and learners, in particular, engaging quickly and more often where there are concerns.

- clarifying learning objectives, skills, and knowledge necessary to achieve desired learning outcomes, and providing information to support parents and whānau.

c) Supporting principals and teachers

ERO recommends that, in 2023, we increase support for principals and teachers. This means:

- school boards ensuring they have a focus on supporting principal wellbeing.

- increasing wellbeing support for principals and teachers and targeting it to those who need it the most.

- supporting principals to deal with staff absences, turnover, and vacancies.

Actions already underway

In response to the impacts of Covid-19, the Government has already undertaken a range of actions to support learners, teachers, and principals. These include:

For learners:

- The Attendance and Engagement Strategy, and the School Attendance Turnaround Package to get learners back to school more regularly.

- Loss of learning initiatives, including targeted funding for additional teaching and tutoring support for students in Years 7-13 who most need opportunities to catch up.

For teachers:

- Reduced staffing ratios for Years 4-8 from 1:29 to 1:28 by the beginning of 2025.

- Free access to counselling to help teachers deal with the mental health impacts of Covid‑19.

- Study awards, sabbaticals, and study grants for teachers to complete further study and participate in professional learning activities.

For principals:

- Access to a range of programmes and funding to help principals manage their wellbeing.

- Providing access to a range of sabbaticals, training, and support

- Supporting recruitment by:

- speeding up processing of Limited Authority to Teach and New Teacher applications.

- providing help for principals and boards to recruit overseas teachers.

Conclusion

Around the world, Covid-19 is having an ongoing impact on schools and learning. Learners have had to focus on learning through lockdowns, community outbreaks, and constant change. While learners are feeling better about their learning now, Covid-19 has left a legacy of increased behaviour concerns, lower attendance, and learning gaps. We need to work together, supporting teachers and principals, to make up for learning gaps and get our learners back on track.

Introduction

Three years ago, Covid-19 arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. Learners, teachers, and principals have adapted to an ever-changing situation and shown remarkable resilience. However, it has had lasting impacts, and these have taken a toll on learner engagement, progress, and achievement, as well as teacher and principal wellbeing and how well they are coping with workload. ERO has collected data throughout the pandemic. This report provides insights into how learners, teachers, and principals are coping now, after most restrictions have been lifted, but community transmission continues.

The story so far

2020-2021

Following the arrival of Covid-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand, the first nationwide lockdown began on 25 March 2020 and saw schools and education facilities close down. Education changed drastically as learning moved from the classroom to the home, bringing with it a range of unique challenges for learners, teachers, principals, and whānau. During this lockdown, schools learned how to deliver education remotely, with many teachers and principals going above and beyond to keep learners engaged and supported through a difficult learning period.

Schools returned to the classroom in May 2020, but Covid-19-related disruptions continued. In August 2021, the second nationwide lockdown began in response to the spread of the more contagious Delta variant of Covid-19. This lockdown came with little warning. Despite this, schools adjusted their practice and showed innovation when it came to the remote delivery of education and wellbeing support for their learners, expanding on and using knowledge from their experiences during the 2020 lockdown.

Upon returning to the classroom once more, teachers and principals supported learners and their whānau with concerns about learning progress, attendance, and Covid-19‑related anxiety. Both the lockdown and reintroduction periods presented staff with an unfamiliar set of challenges, created new responsibilities, and required complex and high-stake problems to be solved quickly as the situation unfolded around them. As would be expected, these transition periods had significant impacts on the wellbeing and workloads of learners, teachers, and principals.

Our key findings at that time included:

- Learners struggled more after lockdown than when they were in lockdown. There was a heightened sense of anxiety among learners, and senior secondary learners particularly were worried about their workload.

- Teachers and principals were concerned about ongoing disengagement, especially concerning attendance. We found that learners preferred to learn at school.

- Teacher and principal wellbeing had declined. Teachers and principals were increasingly struggling with their workload.

- The impact was greater in Auckland, where there had been more cases and more lockdowns.

- Principals and teachers had changed their practices to respond to Covid-19, which included strategies to re-engage with learners and communicating more frequently with whānau.

2022-2023

The Covid-19 pandemic has continued to disrupt school operations across the country. In 2022, we learned to live with large scale community transmission, which had a big impact on learner and staff absence from school.

Covid-19 transmission in the community peaked in March 2022 and remained relatively high throughout the 2022 school year. Ministry of Health data from 2022 showed that teachers (41 percent) and child carers (38 percent) had the highest rates of Covid-19 infection among any occupational group in the country.1 Additionally, regular attendance (attending more than 90 percent of half-days) fell from around 60 percent in Term 2 of 2021, to just 40 percent in Term 2 of 2022, likely due to Covid-19-related absences.2

Now, in 2023, we are more accustomed to having Covid-19 in our community, but it continues to have impacts. These impacts come alongside other disruptions from Cyclone Gabrielle and flooding in Auckland. This report looks at how the past three years have had a cumulative impact and where we are now.

ERO’s Learning in a Covid-19 World series

This report continues and updates ERO’s Learning in a Covid-19 World series of reports. ERO has undertaken this research to understand how learners, teachers, and principals are doing now, three years after the pandemic began. Uniquely, we have collected data on learner, teacher, and principal perspectives at various points over the last three years, so can show how things have changed over time. Links to our series of reports can be found in Appendix 1.

This report

For this report, ERO has focused on the experiences of learners, principals, and teachers. We received responses to surveys from:

- 3,052 learners in Years 4 to 13, from 98 schools

- 1,209 principals

- 349 teachers, from 64 schools.

The responses came from primary, intermediate, composite, and secondary English-medium schools across the country, of a range of sizes from very small to very large, and across urban and rural locations.

For the teacher and learner surveys, the target population were schools that participated in earlier rounds of our research as well as an additional randomly selected set of English‑medium schools across Aotearoa New Zealand, except in those areas that had been heavily affected by Cyclone Gabrielle. For the principal survey, we invited all principals in English-medium schools to participate, except those in areas who had been heavily affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

Due to different response rates, we had a skewed sample of learner respondents, with learners from lower socio-economic status (SES) communities overrepresented. Overall proportions reported for the learner survey were weighted to bring these in line with population parameters. In this report, to maintain comparability with previous reporting, we used school decile as a proxy for low, mid and high SES. This measure is now deprecated.

The survey was active between 8 March and 31 March 2023. Although not intentional, some responses were recorded during the teachers’ strike on 16 March. Overall, we received 3,052 responses from learners, 1,209 from principals, and 349 from teachers. The small proportion of responses collected during the strike did not differ in any systematic way from other responses.

We compared these responses to the findings from our previous Learning in a Covid-19 World series of reports. We have reported time series data when it was available, but it is important to note that not all questions were repeated at each time point, and ERO undertook no surveys in this area during 2022.

We have also conducted statistical analyses to understand the contribution of different factors to wellbeing outcomes.

We would like to thank all the learners, principals, and teachers who have given their time and shared their experiences with us.

More information regarding the respondent demographics, survey questions, and analysis can be found in the Appendices.

Structure of this report

Part 1 looks at how learners are doing – their wellbeing, engagement, and learning.

Part 2 looks at how Māori and Pacific learners, and learners from ethnic communities are doing.

Part 3 sets out how teachers and principals are doing – their wellbeing and how they are managing their workload.

In each part, we describe what we found in our latest set of surveys and, where we have comparable data, how this compares to our previous findings. Where we report differences, they have been tested and found to be statistically significant at p < 0.05.

In Part 4, we look ahead to how the system will need to respond to ‘Long Covid’.

Part 1: How are learners doing?

Three years after the pandemic began, learners are feeling safer from Covid-19, and happier at school. They are more connected with their friends and half have an adult at school who cares about them.

But the pandemic has affected crucial years of education and, for the youngest learners, all their education. This will have lasting impacts. Learners do feel like they are progressing well in their learning, but principals and teachers are increasingly worried about learning achievement and progress. They told us that many learners are behind on their learning. These concerns are much more evident in schools in lower socio-economic communities.

ERO found previously that during and after the disruptions of 2020 and 2021, learners’ wellbeing and progress had been disrupted.

This section looks at how things are going in 2023 with:

- learner wellbeing

- learner engagement

- learner progress and achievement.

1. Learner wellbeing

Wellbeing is critical for learning to occur. This means that learners need to feel safe, positive, and connected to their peers. This section looks at learners’ views of:

- happiness

- connectedness

- safety.

a) Happiness

Learners are happier at school in 2023

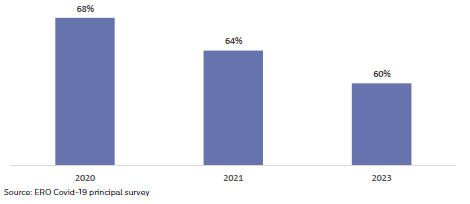

Now that schools are open and not impacted by lockdowns, learners’ happiness has increased. Sixty-eight percent of learners reported feeling happy most or all of the time in 2023, an increase from 61 percent in 2021 and 62 percent in 2020.

Figure 1: Learners who feel happy all or most of the time

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

The most important reported driver of happiness at school is being connected to friends

The other key drivers of learners feeling happy are:

- feeling safe from Covid-19

- having their teacher care about their wellbeing

- having an adult who cares for them at school.

“I felt anxious but now I’m not because I’m better at learning and my friends are by my side.” (Learner)

Teachers and principals still have concerns about learner wellbeing

It is positive to hear that learners are generally doing better, but not all learners are doing well. While happiness at school has improved, in 2023, 28 percent of learners are only happy at school sometimes.

Teachers and principals are worried about ongoing impacts on learner wellbeing, particularly in secondary schools.

“We have so many children in need of counselling and displaying severe anxiety - it is impacting their learning… It is incredibly stressful as a tumuaki leading a kura with this level of anxiety - teachers included.” (Principal)

A third of teachers and principals are concerned that learner wellbeing is worse than they would expect at the start of the year

Thirty-six percent of teachers surveyed, and 38 percent of principals, are concerned that learner wellbeing is worse or much worse than they would expect at this time of year.

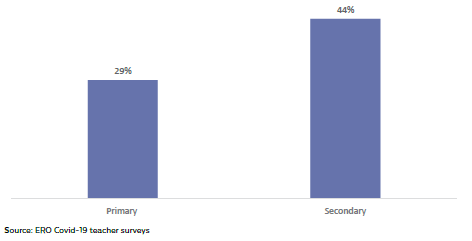

Secondary school learners have had to contend with both learning disruptions and assessment disruptions. More secondary teachers think that their learner wellbeing is worse than they would expect (44 percent), than primary teachers (29 percent).

Figure 2: Teachers: Learner wellbeing is worse than I would expect at this time of year

Source: ERO Covid-19 teacher surveys

b) Connectedness

Learners feel more connected to their friends than in previous years

Seventy-six percent of learners feel connected to their friends compared with 64 percent in 2021.

Figure 3: Learners: In the past week, I have felt connected to my friends

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Half of learners have an adult at school who cares about them

Half (51 percent) of learners say they have an adult who cares about them at school, which has remained consistent throughout the pandemic.

c) Safety

Learners are less worried about Covid-19

Learners are more comfortable living with Covid-19. Despite Covid-19 now being in the community, three quarters of learners (75 percent) feel safe from Covid-19, up from just over half (58 percent) after lockdown in 2020, and two-thirds (69 percent) in June and July 2021.

In 2021, anxiety about Covid-19 was higher in Auckland, which had more cases. Now that Covid-19 is in all communities across Aotearoa New Zealand, there are no differences in feeling safe between Auckland learners and other learners.

Figure 4: Learners: I feel safe from Covid-19, over time

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

2. Learner engagement

To learn, learners need to be present and actively participating in their schooling. This section looks at:

- learner enjoyment

- attendance and engagement

- behaviour.

a) Learner enjoyment

More learners are enjoying their learning

In 2021, we found that learners generally preferred to learn at school, likely due to the opportunity to engage one-on-one. Now that learners are back in school:

- more learners are enjoying their learning. In 2023, over half of learners (53 percent) are enjoying their learning, compared to 46 percent in 2021

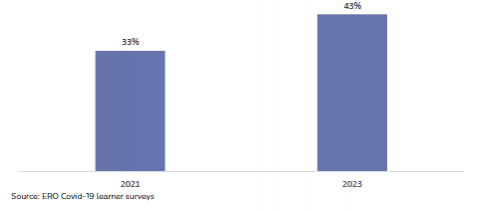

- in particular, more older learners are enjoying their learning. In 2023, 43 percent of learners in Year 11–13 are enjoying their learning, compared to 33 percent in 2021.

Figure 5: Year 11-13 learners: I am enjoying my learning

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

The increase in enjoyment of learning may be because learners are seeing their learning progress

We looked at the most important reported drivers of enjoyment of learning, which are:

- having a teacher who cares about their learning

- being able to keep up with their learning

- believing that their learning is progressing.

The increase in enjoyment of learning may be due to more learners feeling like they are keeping up and progressing now that they are back in the classroom, and are getting positive reinforcement from their teachers.

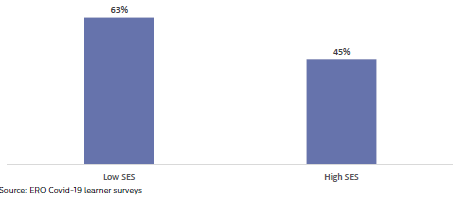

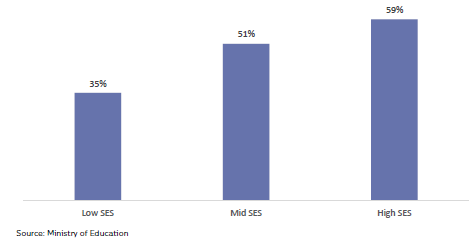

Learners in lower SES communities are more likely to be enjoying their learning

Learners from schools serving low SES communities are more likely to report enjoying their learning (low SES; 63 percent) compared to learners from schools serving high SES communities (high SES; 45 percent). These learners are more likely to say that their teachers care about their learning and that their learning is progressing, which we know are two key drivers.

Figure 6: Learners: I am enjoying my learning by SES group

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

b) Attendance and engagement

Attendance and engagement are increasingly concerning

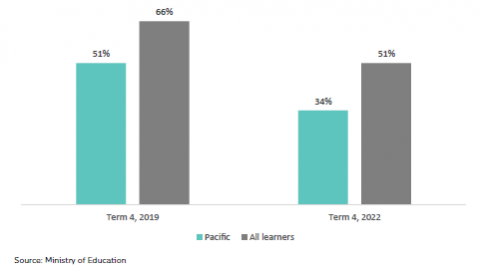

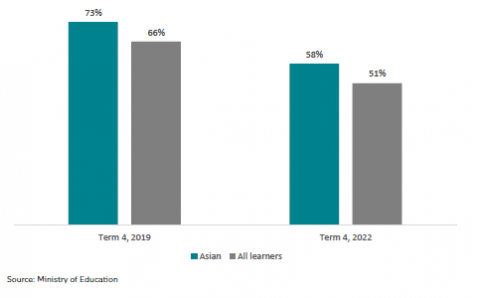

Covid-19 has had a serious impact on learner attendance. The disruptions from rates of Covid‑19 in the community in mid-2022 meant that regular attendance dropped to a low of 40 percent in Term 2 of 2022. However, attendance rates have not recovered fully. By Term 4 of 2022, still only 51 percent of learners were regularly attending school.

Figure 7: Learners regularly attending school in Term 4 from 2019 to 2022

“Although we are back to "normal" regarding the day-to-day business of the school, the effects of Covid on student learning, engagement and attendance is still having an impact on the school. Student attendance is an issue (like most schools) which affects engagement and achievement.” (Principal)

c) Behaviour

Learner behaviour is a significant issue.

Principals are concerned about learner behaviour, with 41 percent saying that behaviour is worse or much worse than they would expect at this time of year. This proportion has not changes significantly since 2021 (39 percent).

“There is a low level of disruptive and unsettled behaviour with some of our Year 7-8 students. They seem to be operating in a bit of flight or fight mindset. The disruption during former years when they were at primary seems to be impacting upon their choices when it comes to interacting with other students. Their decision making seems rather impulsive.” (Principal)

“[Need] support for the number of five-year-olds entering school with high behaviour needs, lack of toilet training, poor communication skills.” (Principal)

Changes and issues within the family, community, the way schools are run and learning can all impact on learner behaviour.3 The increase in principals’ concerns may reflect learners being disengaged from school (i.e., not attending or not enjoying learning) and struggling to keep up, or trauma following Covid-19.

3. Learning and achievement

Covid-19 has seriously impacted learners’ achievement and progress. Learners are more positive about their learning progress, but teachers and principals are increasingly concerned. Without the Covid‑19 modifications to NCEA that were put in place over the last three years, secondary school qualification attainment would be much lower than it was before the pandemic.

Learners’ progress and achievement are most concerning in lower SES communities. ERO’s previous reporting showed that learning from home during lockdowns presented greater challenges for learners in low SES communities. Principal and teacher concerns about attendance, engagement, and learning were also greater in these schools.

This section sets out:

- learners’ views on their progress

- teachers’ and principals’ views on learners’ progress

- subject areas where learners are behind

- qualification attainment

- differences in low SES communities.

a) Learners’ view on progress

Learners are more positive about their learning

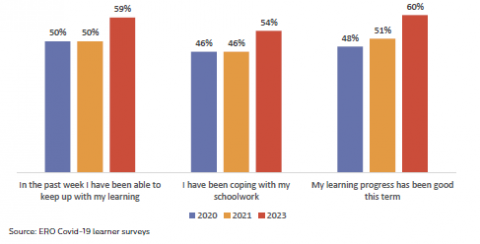

This year, 60 percent of learners feel their progress has been good compared to only 48 percent of learners in 2020. Learners are also more likely to say they are coping and keeping up with their schoolwork this year compared to 2020 and 2021. This outcome is encouraging and may reflect the effort schools have made to adjust learning to where learners are at.

Figure 8: Learner perceptions of learning over time

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

However, not all learners feel like they are progressing well. Learners who feel that they are not progressing are:

- more likely to find it challenging to keep up with their schoolwork

- less likely to enjoy learning.

b) Teacher and principal views

Principals are increasingly concerned about learning

Concerningly, nearly half (43 percent) of principals say that learning is worse than they would expect at this time of year, which has increased substantially from 27 percent in 2021.

Figure 9: Principals reporting learning being worse than they would expect

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

More than a quarter of principals say their struggling learners are two or more curriculum levels behind

For learners that are behind, half (50 percent) of principals say that they are one curriculum level behind, and just over a quarter (26 percent) say they are two or more curriculum levels behind.

Figure 10: Principals: For those learners who are behind, how behind are they?

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

“The 3 years of constant lockdowns and illness has really set back learning and it will take more than just teachers’ and principals’ goodwill to rectify it.” (Principal)

“We have all these kids arriving back at school post-Covid. Some of them have not attended in several years. They literally do not know their letters, sounds, or how to hold a pen. And age-wise they get placed in a year 3-4 class. It is so hard. Others are arriving having had unlimited access to screens for the last 2 years. They have limited vocab, social skills, learning to learn skills.” (Principal)

c) Subject areas where learners are behind

Learners report most concern about maths, while principals and teachers report most concern about writing

Learners are concerned about maths. Thirty-five percent of learners say that they need to catch up on maths and 26 percent say they need to work on their writing. Female learners are a lot more likely to say they need to catch up on maths compared to male learners (42 percent compared to 29 percent).

In contrast, both principals (51 percent) and teachers (44 percent) are more concerned about writing.

“We have students who are up to 3 levels behind but just as scary is that many of our average students are also a level behind just because work has been missed being taught. Huge learning gaps in maths and writing. It is a lot of schoolwork to catch up.” (Principal)

Figure 11: Principals and learners: Learning area of most concern

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal and learner surveys

Principals’ and teachers’ concerns are likely to be based on their information on learners’ progress. Learners’ concerns about math may reflect more general anxiety about math, which can be a particular concern for female learners.4

d) Qualification attainment

NCEA attainment has fallen

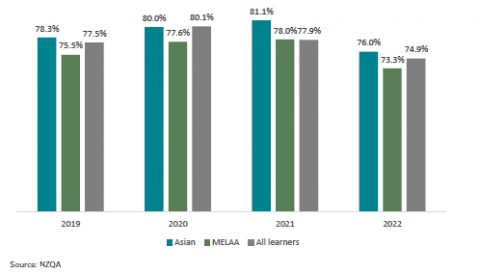

Attainment rates for NCEA Level 2, Level 3, and University Entrance (UE) have declined each year since 2020.

If the Covid-19 modifications were not in place, attainment in 2022 would have been lower. From 2020 to 2022, the modifications made included Learning Recognition Credits (LRCs), with one LRC credit being awarded for every five credits earned through assessment, to a maximum of eight credits at NCEA Level 2 and 3 for each learner. 5

Figure 12: NCEA attainment 2019 - 2022

Source: NZQA

e) Low SES communities

Learners in low SES communities are more likely to be behind

Principals and teachers in schools serving lower SES communities are more concerned about learning progress and achievement. They told us that learners are behind on their learning. Over half (53 percent) of principals from schools serving low SES communities say that learning is worse or much worse than expected, compared to 31 percent of principals from schools in high SES communities.

Figure 13: Principals from low SES and high SES schools who say learning progress is not as expected

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

“Students entering the school in Year 9 are generally below the expected curriculum levels in reading, literacy, and maths. This presents us with problems in the senior school.” (Principal)

Learners in low SES communities have fallen further behind

Learners in schools serving low SES communities are more likely to say they need to catch up on their learning (33 percent), compared to learners in schools serving mid SES communities (20 percent) or schools serving high SES communities (19 percent).

Figure 14: Learners who report needing to catch up on their learning

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

“I [have fallen] behind in my learning, like my fractions, because I had Covid and I missed out on the big talk… I am still trying to recover and learn my fractions.” (Learner)

Principals in schools serving low SES communities are three times more likely to report that their struggling learners are two or more curriculum levels behind, compared to those in schools serving high SES communities (46 to 14 percent).

PIRLS suggests greater concern in low SES communities

Key findings from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2021 indicate that during the first year of the pandemic, teachers, principals, and learners reported concern about declining learning progress. Principals and teachers in schools serving low SES communities were more likely to report that curriculum delivery was impacted, and that student learning was impacted ‘a lot’. On the other hand, about 50 percent of parents from mid to high SES schools did not think learning was adversely affected.

NCEA attainment gap has widened

Even with Learning Recognition Credits, the attainment rate for Year 12 NCEA Level 2 in schools serving low SES communities has dropped nearly 4 percentage points, from 69.7 percent in 2019 to 66.0 percent in 2022. In schools serving high SES communities, the drop is less than a percentage point, from 84.2 percent in 2019 to 83.8 percent in 2022. The gap between schools serving low and high SES communities has widened from 14.5 percentage points in 2019 to 17.8 percentage points in 2022.

Figure 15: NCEA Level 2 attainment of schools serving low and high SES communities

Source: NZQA

Potential causes

This increase in inequity may reflect that Covid-19 did not impact on all communities equally.

Learners in schools serving low SES communities faced more challenges due to Covid-19 than those in schools serving mid or high SES communities. Access to digital devices and the internet was a significant challenge for learners in schools serving low SES communities, and these communities have been impacted by Covid‑19 more broadly.

Attendance rates have also been more impacted in lower SES communities. Attendance is critical to learners’ progress and achievement and could be a key driver of the increased gap in outcomes.

Figure 16: Percentage of learners attending school more than 90 percent in Term 4 of 2022

Source: Ministry of Education

Conclusion

Overall, three years on from the beginning of the pandemic, while there are some welcome improvements in learners’ wellbeing, learning gaps due to Covid-19 disruptions are increasingly evident. There have been lost learning opportunities for all, and inequities in outcomes have increased.

Part 2: How are Māori learners, Pacific learners, and learners from ethnic communities doing?

Covid-19 has impacted different groups differently. Māori and Pacific learner wellbeing has improved but their learning has been more impacted. Learners from ethnic communities’ progress has been less impacted but they face more wellbeing challenges.

The impact of Covid-19 has not been even. This section of the report sets out the impact Covid-19 has had on Māori learners, Pacific learners, and learners from ethnic communities (Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American, African) and their:

- wellbeing

- engagement

- learning and achievement.

Due to sample size, we are not able to report with confidence on time series shifts for these groups, but we have drawn comparisons to other groups for our 2023 findings.

1. Māori learners

Wellbeing

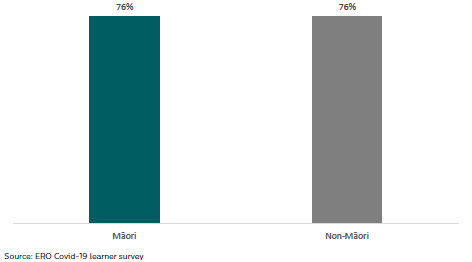

Most Māori learners feel connected to their friends

Seventy-six percent of Māori learners say they are feeling connected to their friends, which is the same proportion as for non‑Māori.

Figure 17: Māori learners feeling connected with their friends

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner survey

Engagement

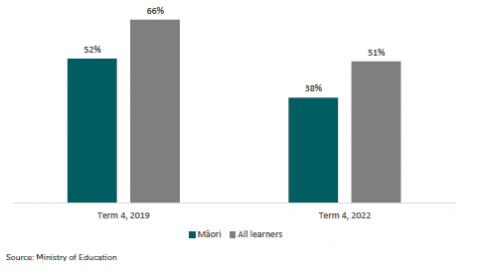

Māori learners’ attendance has fallen and is lower than all learners

In Term 4 of 2022, regular attendance for Māori learners was 38 percent, which is a 14 percentage point drop since Term 4 of 2019, when 52 percent of Māori learners attended school regularly.

Māori learners are less likely than all learners to be attending regularly. This may reflect higher rates of illness due to Covid-19 during 2022, or isolation requirements for those learners living in multi-generational households, or broader barriers.7

Figure 18: Attendance for Māori learners and all learners

Source: Ministry of Education

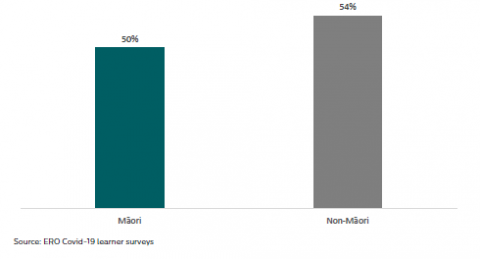

Fewer Māori learners are enjoying their learning

In 2023, Māori learners (50 percent) are less likely to be enjoying their learning than non-Māori learners (54 percent) and have not seen the improvement in enjoying their learning experienced by other learners.

Figure 19: Māori learners who are enjoying their learning

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Learning and achievement

Māori learners are less positive about their learning than other learners

Fifty-seven percent of Māori learners say their learning progress has been good this term, which is less than non-Māori learners (61 percent).

Figure 20: Māori learners: My progress has been good this term

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Māori learners’ NCEA Level 2 attainment has been more impacted

Māori learners’ attainment at NCEA Level 2 has fallen throughout the pandemic. The attainment rate for Level 2 in 2022 was 64.1 percent, which is the lowest it has been since 2014. Without Covid‑19 modifications, it is likely that the impact of the pandemic on achievement would be greater. The gap between Māori and non-Māori learners has increased from 10.4 percentage points in 2019 to 13 percentage points in 2022.

Figure 21: NCEA Level 2 attainment of Māori learners and all learners

Source: NZQA

2. Pacific learners

Wellbeing

Pacific learners feel more connected to their friends than other learners

Positively, 80 percent of Pacific learners feel connected to their friends, which is slightly higher than for non-Pacific learners (75 percent).

Figure 22: Pacific learners feeling connected with their friends

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Pacific learners feel more cared for at school than other learners

Pacific learners are more positive than other learners about feeling cared for at school. Fifty seven percent of Pacific learners say they have an adult at their school who cares about them. This is greater than the 50 percent of non-Pacific learners who feel there is an adult who cares about them at school.

Figure 23: Pacific learners who feel they have an adult who cares about them at school

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Engagement

Pacific learners’ attendance is lower than all learners

In Term 4 of 2022, only about a third of Pacific learners attended school regularly (34 percent), a drop of 17 percentage points compared to Term 4 of 2019 (51 percent). Pacific learners are less likely than all learners to be attending regularly. This may reflect additional barriers to attending that they face.8

Figure 24: Attendance of Pacific learners and all learners in Term 4 of 2019 and 2022

Source: Ministry of Education

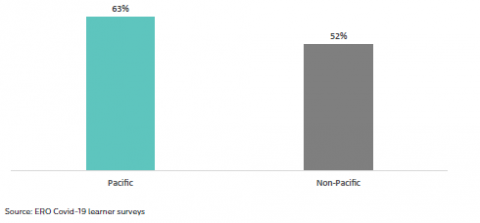

Pacific learners are more likely to enjoy their learning than other learners

Nearly two-thirds of Pacific learners say they are enjoying their learning (63 percent) compared to just over half (52 percent) of non-Pacific learners.

Figure 25: Pacific and non-Pacific learners who are enjoying learning

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Learning and achievement

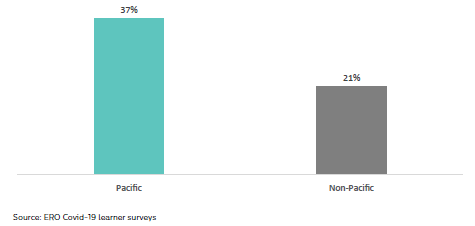

Pacific learners are more likely to feel they need to catch up than other learners

Not all Pacific learners feel up-to-date with their learning. In 2023, more than a third (37 percent) of Pacific learners say they need to catch up on their learning. This is higher than for non-Pacific learners (21 percent).

Figure 26: Pacific learners who report needing to catch up on their learning

Source: ERO Covid-19 learner surveys

Pacific learners' NCEA Level 2 attainment has been more impacted

Pacific learners' attainment of NCEA has been negatively impacted by the pandemic. The attainment rate for Level 2 in 2022 is 67.3 percent, down 4 percentage points from 2019 when it was 71.3 percent. This decline would have been greater without Covid-19 modifications and is greater than for other learners. This lower attainment may reflect the greater impact of Covid‑19 on attendance of Pacific learners as attendance is a crucial driver of attainment.

Figure 27: NCEA Level 2 attainment of Pacific learners

3. Learners from ethnic communities

Wellbeing

Fewer learners from ethnic communities feel that they have an adult who cares for them at school

Only 37 percent of Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African (MELAA) learners, and 43 percent of Asian learners report they have an adult at their school who cares about them, compared to 51 percent of all learners. This matters, as we have found that it is a key driver of happiness at school.

Our data suggest that MELAA learners are less likely than all learners to feel happy most or all of the time. This is consistent with the finding in ERO’s report Education for all our children: Embracing diverse ethnicities,9 that MELAA learners report lower wellbeing than others.

Engagement

Asian learners have higher rates of regular attendance than all learners

More than half of Asian learners (58 percent) attended school regularly in Term 4 of 2022, down 15 percentage points from Term 4 of 2019 (73 percent). The rate of regular attendance for Asian learners remains higher than for all learners (51 percent).

We do not have data available on attendance for MELAA learners.

Figure 28: Asian learners’ regular attendance rate in Term 4 of 2019 and 2022

Source: Ministry of Education

Learning and Achievement

Asian and MELAA learners’ NCEA Level 2 attainment has been less impacted

NCEA Level 2 attainment for Year 12 Asian learners was 76 percent in 2022, which has dropped slightly from 78.3 percent in 2019. The rate for MELAA learners has similarly dropped, to 73.3 percent from 75.5 percent in 2019. This has been a lower fall than that for all learners.

Figure 29: NCEA Level 2 attainment of Asian and MELAA learners

Source: NZQA

Conclusion

Covid-19 has affected different groups differently. Looking ahead, we will need to ensure that the greater impact on Māori and Pacific learners’ learning progress does not become entrenched, and that wellbeing challenges for learners from ethnic communities are addressed.

Part 3: How are teachers and principals doing?

Illness, isolation, staff absences, and looking after learners and their communities have all had a cumulative impact on teachers and principals across the three years of the pandemic. In 2023, teachers surveyed are happier at work, and they are feeling more connected to their teaching team, but principal wellbeing is still low. Both teachers and principals are struggling with their workloads.

The last three years of the pandemic have taken a toll on teachers and principals. Lockdowns and home learning presented new and unprecedented challenges. After lockdowns, catching up learners as they returned to onsite learning, and managing a mix of classroom and home learning, have impacted on workloads. In 2022, school staff have been greatly impacted by absences due to being sick with Covid-19 or isolating. Overall, teachers and principals have been seriously impacted by cumulative pressures and disruptions over the last three years and ongoing community transmission. It is important to recognise that teachers’ and principals’ wellbeing are impacted by Covid‑19 along with, for example, recent extreme weather events and cost of living pressures.

The impact of Covid-19 is far from unique to Aotearoa New Zealand. Workloads and wellbeing have been impacted across the world. In Australia, the shift to remote learning early in the pandemic increased teacher workloads, and ongoing transmission later on impacted on anxiety.10 In Australia,11 the United Kingdom,12 and the United States,13 teacher retention is of concern as teachers face increased behavioural challenges and workload issues caused by staffing shortfalls. In Canada, trouble finding staff and increased administrative responsibilities have impacted on principals’ intentions to stay in the profession, and more than half of teachers report that their stress levels are not manageable.14

1. Wellbeing

There are some indications that teacher wellbeing at work has improved

Teachers we surveyed report being happier at work in 2023 compared to 2020 and 2021, and more connected to their teaching teams. More data would be needed to be confident that this is a real trend.

Figure 30: Teacher wellbeing over time

Source: ERO Covid-19 teacher surveys

Teachers’ reported happiness at work is the same across schools in communities of differing socio‑economic status and between primary and secondary schools.

Factors contributing to teacher wellbeing

The key reported drivers of teachers feeling happy at work are:

- feeling supported by and connected to their teaching team

- feeling satisfied with their life

- their views on workload being manageable.

Teachers are feeling more connected, particularly in primary schools

In 2023, teachers we surveyed are more likely to feel supported by, and connected to, their teaching team compared to previous years.

Figure 31: Teachers: I feel supported by, and connected to, my teaching team

Source: ERO Covid-19 teacher surveys

Teachers in primary schools, in particular, are feeling more connected. Ninety percent of primary school teachers surveyd feel supported by and connected with their school leadership, compared to 77 percent of secondary teachers. Feeling more connected matters to how happy teachers feel at work.

Principal wellbeing has fallen

Principals have been hugely impacted by Covid-19 – from supporting whole communities during the unprecedented lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, to dealing with staffing shortages and absences during 2022.

In 2023, only six in 10 principals (60 percent) say they are happy at work. Principals from schools in Auckland (66 percent) are more likely to be happy at work compared to principals outside Auckland (58 percent). Principals in schools serving low and mid SES communities are less happy at work (55 and 57 percent, respectively) than those in high SES communities (67 percent).

“We do a lot to look after staff wellbeing at my school, but no one really does that for me.” (Principal)

Figure 32: Principals who say they are happy at work

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal survey

Factors contributing to principal wellbeing

The key reported drivers of principals’ happiness at work are:

- finding their workload manageable

- having recovered from disruptions

- feeling connected to, and supported by, their leadership team.

Principals remain connected to their leadership team

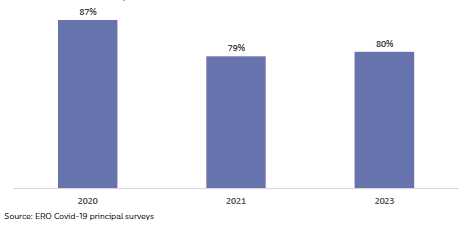

Feelings of connectedness and support with their leadership team is the same as in 2021. Principals in secondary schools (88 percent) feel more connected to their leadership teams than those in primary schools (78 percent).

Figure 33: Principals who feel connected to, and supported by, their leadership team

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

Increasing numbers of principals need support

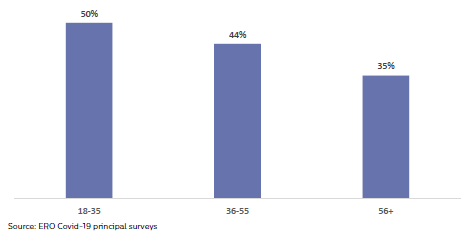

As the impacts of Covid-19 accumulate, the proportion of principals who say they need support for their wellbeing has increased, from 26 percent in 2021 to 41 percent in 2023. Principals who need support are more likely to find their workload unmanageable, are less happy at work, and feel that their school has not recovered from disruptions caused by Covid-19. Younger principals are more likely to say they need support. There are no major differences between principals of secondary and primary schools, or across socio‑economic levels.

Figure 34: Principals needing further support

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

Figure 35: Principals needing further support by age group

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

“Through the wellbeing funding I received last year, [I] was able to target areas of need within our community, including my own capacity to lead. Ongoing directed funding to support wellbeing will make a big difference for our learning community.” (Principal)

In 2023, we also asked principals if they had accessed support for their wellbeing during 2022. The majority (70 percent) had not. Older principals (56 years and over) are the least likely to have accessed support (23 percent).

Just over half of principals (53 percent) who say they need wellbeing support had not accessed support in 2022. It is unclear whether support not being accessed is because of reluctance to access support, difficulty accessing support, or that the nature of the targeted support available did not meet their needs.

2. Coping with workload

Covid-19 has impacted how teachers and principals are coping with workloads in Aotearoa New Zealand and across the world. Early in the pandemic, managing the shift to home learning during lockdown presented unfamiliar challenges. In 2022, dealing with staffing supply through illness, isolation, and difficulties in filling vacancies have had an impact, alongside teachers and principals supporting learners to catch up on learning gaps, and managing learner engagement and behaviour.

Principals and teachers say workloads feel less manageable

In 2020, 42 percent of teachers and 26 percent of principals felt their workload was manageable. For teachers this has dropped to 26 percent in 2023, and for principals it has dropped to 16 percent.

“I'm really worried right now - it seems like a perfect storm. Teachers are struggling with so many things that have got worse - student behaviour, learning and wellbeing while struggling with their own wellbeing, workload, and financial pressures.” (Principal)

Figure 36: Principals and teachers who say their workload is manageable over time

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal and teacher surveys

Female principals and principals of small schools are struggling more

Female principals (45 percent) are more likely to report their workload as unmanageable compared to male principals (38 percent).

Figure 37: Principals who find their workload unmanageable by gender

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

In 2021, we found that school size was related to principal workload – the smaller the school, the more principals struggled with their workload. This remains true in 2023. Principals of very small schools (58 percent) are more than twice as likely to find their workload unmanageable compared to principals of very large schools (28 percent). Often these principals are themselves teaching and undertaking other roles in the absence of support staff.

“In small schools where the principal teaches and holds a large number of other roles, the workload is large, and more staffing support is needed for the wellbeing of both the students and staff.” (Principal)

Figure 38: Principals who find their workload unmanageable by school size

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

Factors contributing to workload manageability

The key reported drivers of workload being unmanageable for principals are:

- not feeling as if their school has recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19

- feeling less connected to, and supported by, their leadership team

- working in smaller schools.

A key driver of workload manageability for teachers is being connected to, and supported by, their teaching team. The data show that teachers who feel less connected to, and supported by, their teaching team are more likely to say their workload is unmanageable.

Covid-19 impacts have accumulated and still linger

Covid-19 impacts are a big driver of principal wellbeing and workload. In 2023, only 19 percent of principals agree that their school has recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19. Fifty-seven percent of principals say that staff wellbeing has not recovered to pre-Covid-19 levels. Principals of schools serving low SES communities are nearly twice as likely (44 percent compared to 24 percent) to say their school has not recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19.

Figure 39: Principals who think their school has not recovered from the disruptions caused by Covid-19 (in 2023)

Source: ERO Covid-19 principal surveys

“The post-Covid environment in the sector has ignored the significant challenges emerging out of three years of disrupted learning, and urgent and immediate responses by teachers to support learning. Students are showing more levels of violence, verbal abuse, lack of impulse control and the need for remedial support with learning than throughout Covid.” (Principal)

Principals report vacancies are difficult to fill

Ability to fill vacancies is important for principal workloads. Nearly a quarter of principals (23 percent) say they are struggling to fill vacancies in 2023. Principals in schools serving low SES communities have more difficulty filling vacancies (31 percent) than those in schools serving high SES communities (18 percent).

“Staffing is a continuing challenge. Lack of experienced staff to deal with challenges in the classroom. Increasing issues with new entrants arriving with behavioural issues and not ready for learning. Lack of relief staff and lack of available teacher aides.” (Principal)

Conclusion

As it has across the world, for the last three years the pandemic has impacted on teacher and principal workload and wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand in different ways. It is positive that some measures of teacher wellbeing have improved, but it is clear that cumulative Covid-19 impacts continue to be felt. The biggest challenge looking forward will be how to support learners to make up learning gaps at the same time as supporting principals and teachers to recover from the impacts of Covid-19.

Part 4: Looking ahead

Three years of disruption have impacted on learners, teachers, and principals. Education in New Zealand has ‘Long Covid’, with lost learning opportunities for all, increases in inequity, and an education workforce under pressure. Addressing these impacts will require sustained and concerted effort from the whole education system. We will all need to help to address learning gaps, reduce inequities in education outcomes, and support teachers and principals to do so.

This report comes after three years of unprecedented disruption for everyone involved in education in Aotearoa New Zealand. It began with the challenges presented by moving schooling from the classroom into the home and proceeded through the difficulties of reintegrating learners into onsite schooling. In 2022, Omicron led to school closures, lost days of learning and disruptions to assessments and exams. Isolation requirements and illness led to significant absences for both staff and learners. The cumulative impact of the past three years means that education in New Zealand has ‘Long Covid’ – a situation that will not easily bounce back to business as usual, with:

- learning gaps for all learners

- increasing inequities in outcomes

- principals and teachers who are struggling.

If unaddressed, the impact of these issues will continue to be felt over the coming decade as learners make their way through school, and principals and teachers may choose to leave the profession.

To recover, ERO recommends action in three areas:

- focusing now on making up for lost learning opportunities

- targeting learning support for those who have been most impacted

- supporting principals and teachers.

a) Making up for lost learning opportunities

Lockdowns, school closures or rostering classes, illness, isolation, and low attendance have combined to significantly reduce the amount of time spent on learning over the last three years. While there are positive signs around improved wellbeing, learning has not recovered. We face a significant learning progress and achievement challenge across all learners. Learners leaving school this year will have had most of their secondary school education disrupted by Covid-19. Learners starting school this year will have had almost all of their early childhood education disrupted.

This report has shown that:

- forty‑three percent of principals say that learning is worse than they would expect at this time of year, which has shifted up significantly from 27 percent in 2021

- NCEA Level 2 attainment rates have dropped in 2022 compared to 2019, and without the Covid‑19 modifications in place, this decline would be sharper.

ERO recommends that, in 2023, everyone in education focuses on helping all learners to catch up on the learning they have missed. This means:

- Getting more learners to school every day to maximise their time for learning, for example:

- through schools’ attendance strategies, increasing understanding of the importance of attendance and awareness of how often learners are attending school

- by identifying and tackling specific barriers to attendance.

- Understanding and addressing learning gaps of all learners, for example by:

- being clear where learners should be at in all year levels and subjects and planning early - this includes diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments, identifying barriers to learning, and having plans to tackle those barriers

- prioritising addressing learning gaps in reading, writing, and numeracy, including through the wider curriculum

- monitoring the effectiveness of remedial responses and adapting as necessary.

- Addressing these gaps through accelerating learning, for example by:

- helping learners, parents and whānau understand their own progress through timely, relevant, and tailored feedback

- as the new common practice model is adopted, focus on using an adaptive teaching approach, recognising that learners learn at different rates and require different forms and levels of support

- providing tailored group and individual acceleration programmes by scaffolding learning to help students who need support so they can continue to progress.

b) Targeting support to those who most need it

The impact of Covid-19 has not been even. Those learners who were previously disadvantaged faced additional challenges in learning from home, barriers to returning to onsite schooling, and often greater impacts of Covid-19 in their community.

This report has shown that the impact on learning progress and achievement has not been equal:

- NCEA results show more of a decline for learners in schools serving low SES communities and for Māori and Pacific learners

- principals in schools serving low SES communities are more likely to report that their struggling learners are significantly behind (two or more curriculum levels) compared to those in schools serving high SES communities (46 to 14 percent).

ERO recommends that, in 2023, we put in place significant, targeted, and tailored learning support for learners who need it the most. This means:

- Identifying which learners have been most impacted, for example by:

- recognising the particular challenges faced by schools and learners in poorer communities.

- teachers, counselling staff, teacher aides, and other staff working together to assess learner needs – including knowing barriers to learning.

- using school-wide data to make informed decisions. This includes identifying patterns of attendance, academic achievement, behavioural and socio-emotional needs, engagement in school, and interaction with peers.

- Having multi-tiered, targeted, and sufficiently intensive support for learning, for example by:

- providing explicit and systematic instruction – this has been found to be effective in reading, writing, and mathematics

- breaking down content or tasks to enhance clarity, adapting lessons whilst maintaining high expectations for all learners, and making sure learners have opportunities to meet those expectations.

- Connecting and working with their parents and whānau to support learning, for example by:

- increasing engagement of parents and whānau, teachers, and learners, in particular engaging quickly and more often where there are concerns.

- clarifying learning objectives, skills, and knowledge necessary to achieve desired learning outcomes, and providing information to support parents and whānau.

c) Supporting principals and teachers

Covid-19 has put principals and teachers under pressure. We are seeing the cumulative impact of three years of unprecedented disruption, additional responsibilities, ongoing uncertainties, an increase in challenging learner behaviour, the need to provide additional support to learners, and staffing shortages due to illness and isolation. If we are to expect principals and teachers to address learning gaps, we will need to ensure they have the capacity to do so.

This report has shown that:

- principal wellbeing has fallen, with only 60 percent feeling happy at work in 2023

- principals and teachers are struggling to manage their workload, with only 26 percent of teachers and 16 percent of principals saying they are managing.

ERO recommends that, in 2023, we increase support for principals and teachers. This means:

- school boards ensuring they have a focus on supporting principal wellbeing

- increasing wellbeing support for principals and teachers and targeting it to those who need it the most

- supporting principals to deal with staff absences, turnover, and vacancies.

Actions already underway

In response to the impacts of Covid-19, the Government has already undertaken a range of actions to support learners, teachers, and principals. These include:

For learners:

- The Attendance and Engagement Strategy and the School Attendance Turnaround Package to get learners back to school more regularly.

- Loss of learning initiatives, including targeted funding for additional teaching and tutoring support for students in Years 7-13 who most need opportunities to catch-up.

For teachers:

- Reduced staffing ratios for Years 4-8 from 1:29 to 1:28 by the beginning of 2025.

- Free access to counselling to help teachers deal with the mental health impacts of Covid‑19.

- Study awards, sabbaticals, and study grants for teachers to complete further study and participate in professional learning activities.

For principals:

- Access to a range of programmes and funding to help principals manage their wellbeing.

- Providing access to a range of sabbaticals, training, and support.

- Supporting recruitment by:

- speeding up processing of Limited Authority to Teach and New Teacher applications.

- providing help for principals and boards to recruit overseas teachers.

Resources and links schools can use

For learners:

- Te Mahau – All in for learning | Kia kotahi te ū ki te ako

- ERO – Attendance: Getting Back to School

- Assessment Online (tki.org.nz)

- Learn about PaCT » Curriculum Progress Tools (education.govt.nz)

- School-initiated supports

- Accelerating learning in mathematics (tki.org.nz)

- Te Kura – Summer School

For teachers and principals:

- Wellbeing@School

- Workforce Wellbeing Package

- Managing staff | Te Mahau

- Navigator service to support overseas teacher recruitment

- Beginning Principal Support programme

- First time U1/U2 principal release allowances

Conclusion

Around the world, Covid-19 is having an ongoing impact on schools and learning. Learners have had to focus on learning through lockdowns, community outbreaks, and constant change. Aotearoa New Zealand is no different. While learners are feeling better about their learning now, Covid-19 has left a legacy of increased behaviour concerns, lower attendance, and learning gaps. We need to work together, supporting teachers and principals, to make up for learning gaps and get our learners back on track.

Appendix 1: Previous reporting

ERO’s Learning in a Covid-19 World series

Te Ihuwaka, ERO’s Education Evaluation Centre, has published multiple reports, guides, and summaries during the pandemic, including:

- Covid-19 Learning in Lockdown (June 2020)

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Schools (January 2021)

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Secondary School Engagement (January 2021)

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Teachers and Principals (December 2021)

- Learning in a Covid-19 World: The Impact of Covid-19 on Pacific Learners (May 2022)

Te Pou Mataaho, ERO’s Māori-medium research and evaluation group, has also published a range of reports, including:

- Te Kahu Whakahaumaru (December 2020)

- Te Muka Here Tangata (May 2021)

- He Iho Ruruku – Te Aho Matua perspectives (January 2022)

- He Iho Ruruku – Ngā Kura ā Iwi perspectives (January 2022)

Appendix 2: Methodology

For this investigation, ERO used a survey research design, yielding primarily quantitative data. Data were collected across surveys of learners, principals, and teachers. The questionnaires used are listed in Appendices 3 through 5 of this report. We repeated many of the same questions that we had used in 2020 and 2021 surveys.

For the teacher and learner surveys, the target population were schools that participated in earlier rounds of our research, as well as an additional randomly selected set of English‑medium schools across Aotearoa New Zealand, except those areas that had been heavily affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

For the principal survey, we invited all principals in English-medium schools, except those in areas who had been heavily affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

Participation in our surveys was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the survey. Schools were identified in the survey for demographic analysis purposes, but no individual school analysis was undertaken.

Due to different response rates, we had a skewed sample of learner respondents, with learners from lower SES communities overrepresented. Overall proportions reported for the learner survey were weighted to bring these in line with population parameters.

The survey was active between 8 March and 31 March 2023. Although not intentional, some responses were recorded were during the teacher strike on 16 March. We received 3052 responses from learners (from 98 individual schools), 1209 from principals, and 349 from teachers (from 64 individual schools).

Data were cleaned and analysed using STATA. ERO reported on aggregated survey results, without identifying information about individual schools’ responses.

Schools were given access to their own survey data to help with their own evaluation and planning. For school size breakdowns, roll sizes are used to define the school and differ for primary and secondary schools, described in the table below:

|

|

Very Small |

Small |

Medium |

Large |

Very Large |

|

Primary |

1-30 |

31-100 |

101-300 |

301-500 |

501+ |

|

Secondary |

1-100 |

101-400 |

401-800 |

801-1500 |

1501+ |

Appendix 3: Correlation and Regression Matrices

Learners: I feel happy (logistic regression)

|

Logistic regression |

Number of obs |

= |

2,122 |

|

|

LR chi2(4) |

= |

294.38 |

|

Prob > chi2 |

= |

0.0000 |

|

|

Log likelihood = -1103.2703 |

Pseudo R2 |

= |

0.1177 |

|

Response variable: I feel happy (agree/strongly agree) |

Odds Ratio |

Std. Err. |

z |

P>z |

[95% Conf. |

Interval] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have an adult who cares for me |

.864532 |

.0460125 |

-2.74 |

0.006 |

.7788935 |

.9595863 |

|

I feel connected to my friends |

.6147983 |

.0334766 |

-8.93 |

0.000 |

.5525653 |

.6840403 |

|

I feel safe from Covid-19 |

.7679578 |

.0343911 |

-5.90 |

0.000 |

.7034259 |

.8384097 |

|

My teacher cares about my wellbeing |

.7533327 |

.0462177 |

-4.62 |

0.000 |

.6679821 |

.8495889 |

|

_cons |

31.74144 |

5.64558 |

19.44 |

0.000 |

22.3991 |

44.98033 |

|

Note: _cons estimates baseline odds. |

||||||

Learners: I am enjoying my learning (logistic regression)

|

Logistic regression |

Number of obs |

= |

1,991 |

|

|

LR chi2(6) |

= |

665.62 |

|

Prob > chi2 |

= |

0.0000 |

|

|

Log likelihood = -1010.1782 |

Pseudo R2 |

= |

0.2478 |

|

Response variable: I am enjoying my learning |

Odds Ratio |

Std. Err. |

z |

P>z |

[95% Conf. |

Interval] |

|

I have an adult who cares |

.7327162 |

.0397394 |

-5.73 |

0.000 |

.6588252 |

.8148944 |

|

My teacher cares about my learning |

.5077534 |

.039947 |

-8.61 |

0.000 |

.4351965 |

.5924071 |

|

In the past week, I have been coping with my school work |

.8026944 |

.0412484 |

-4.28 |

0.000 |

.7257871 |

.8877512 |

|

My learning progress has been good this term |

.5765835 |

.0452363 |

-7.02 |

0.000 |

.4944022 |

.6724251 |

|

In the past week, I have kept up with my school work |

.5855133 |

.0415588 |

-7.54 |

0.000 |

.5094715 |

.6729048 |

|

I need to catch up |

.7993457 |

.0336707 |

-5.32 |

0.000 |

.736003 |

.8681398 |

|

_cons |

535.1 |

187.9713 |

17.88 |

0.000 |

268.796 |

1065.239 |

Learner: My learning is progressing (Spearman’s Correlation)

|

|

I need to catch up on my learning |

I am coping with my schoolwork |

I have kept up with my school work |

I am enjoying my learning |

|

My learning is progressing |

-0.2256 * |

0.4653* |

0.5134* |

0.4780* |

|

* Significant at .05 level |

|

|

|

|

Learner: I need to catch up on my learning (logistic regression)

|

Logistic regression |

Number of obs |

= |

2,304 |

|

|

LR chi2(6) |

= |

244.37 |

|

|

Prob > chi2 |

= |

0.0000 |

|

Log likelihood = -1215.5561 |

Pseudo R2 |

= |

0.0913 |

|

Response variable: I need to catch up on my learning |

Odds Ratio |

Std. Err. |

z |

P>z |

[95% Conf. |

Interval] |

|

|

||||||

|

I am enjoying learning |

.8035155 |

.0428664 |

-4.10 |

0.000 |

.7237423 |

.8920817 |

|

I have been able to keep up with my school work in the past week |

1.886663 |

.1080717 |

11.08 |

0.000 |

1.686304 |

2.110827 |

|

My teacher cares about my learning |

.9377187 |

.0588897 |

-1.02 |

0.306 |

.8291178 |

1.060545 |

|

My learning progress has been good this term |

1.150699 |

.0744371 |

2.17 |

0.030 |

1.013675 |

1.306246 |

|

School size |

.8755513 |

.0568637 |

-2.05 |

0.041 |

.7709023 |

.9944063 |

|

Decile group |

.607253 |

.0412751 |

-7.34 |

0.000 |

.5315124 |

.6937866 |

|

_cons |

.384766 |

.1016423 |

-3.62 |

0.000 |

.2292649 |

.645737 |

|

Note: _cons estimates baseline odds. |

||||||

Teacher: I am happy at work (logistic regression)

|

Logistic regression |

Number of obs |

= |

307 |

|

|

LR chi2(8) |

= |

148.12 |

|

|

Prob > chi2 |

= |

0.0000 |

|

Log likelihood = -111.66162 |

Pseudo R2 |

= |

0.3988 |

|

I am happy |

Odds Ratio |

Std. Err. |

z |

P>z |

[95% Conf. |

Interval] |

|

My workload is manageable |

.4742897 |

.0672416 |

-5.26 |

0.000 |

.3592246 |

.6262118 |

|

I feel supported and connected to my teaching team |

.3291393 |

.0818262 |

-4.47 |

0.000 |

.2021927 |

.5357892 |

|

Years teaching |

.8476401 |

.1678989 |

-0.83 |

0.404 |

.5749197 |

1.249729 |

|

Age group |

1.061997 |

.3308257 |

0.19 |

0.847 |

.5767172 |

1.955615 |

|

I am satisfied with my life |

.4651746 |

.1074746 |