Summary

In 2020, there was a concern that students in Auckland were struggling to cope due to experiencing two Covid-19 lockdowns. In Term 3 2020, ERO found that just under a third of NCEA students (28 percent) felt they were not up to date with their learning, and one out of three NCEA students told ERO that they were not feeling positive about the rest of the 2020 school year.

There was a risk that the disruption to NCEA students’ learning could make it harder for them to transition into further education or employment if they did not achieve the necessary University Entrance and NCEA accreditations.

In September 2020, Cabinet approved funding of up to $2.7M for the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to expand existing Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu (Te Kura) services to Auckland NCEA students.

Following the implementation of the support package for Auckland students, ERO undertook an evaluation of the three Te Kura programmes aimed at supporting young people in Auckland to achieve their NCEA aspirations. It was important to learn how effective the programmes were, to inform future responses.

Whole article:

Responding to the Covid-19 crisis: Supporting Auckland NCEA studentsIntroduction

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has had a profound impact on all aspects of life around the world. In Aotearoa New Zealand, significant disruption to schooling occurred in 2020 due to national and local lockdowns, school closures, and from the ongoing uncertainty caused by Covid-19. Auckland NCEA students were particularly impacted, and extra support was provided to them.

In 2020, there was a concern that students in Auckland were struggling to cope due to experiencing two Covid-19 lockdowns. In Term 3 2020, ERO found that just under a third of NCEA students (28 percent) felt they were not up to date with their learning, and one out of three NCEA students told ERO that they were not feeling positive about the rest of the 2020 school year.

There was a risk that the disruption to NCEA students’ learning could make it harder for them to transition into further education or employment if they did not achieve the necessary University Entrance and NCEA accreditations.

Additional support for Auckland NCEA students

In September 2020, Cabinet approved funding of up to $2.7M for the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to expand existing Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu (Te Kura) services to Auckland NCEA students. Te Kura (formerly known as The Correspondence School) is a state-funded distance education provider, who provides learning programmes and courses, mostly through online delivery, from early childhood to NCEA Level.

The additional funding:

- provided up to 400 extra places for disengaged students and students at risk of disengaging to access a term-length version of the Te Kura Big Picture Programme

- extended the Te Kura Dual Tuition offering for students still enrolled at school but at risk of disengaging

- provided additional Te Kura Summer School places to support students to achieve up to 10 additional credits to gain NCEA accreditation or University Entrance

- provided up to 3000 additional places, allocated by the Ministry of Education, for students to participate in Targeted Dual Tuition and Summer School.

The government also provided additional support to Auckland NCEA students, including:

- extra NCEA credit recognition (for Auckland students this meant 1 additional credit for every four credits attained, up to 16 credits for Level 1 and up to 12 credits for Level 2 and 3)

- lower requirements for University Entrance and certificate endorsements

- the establishment of a $14.5M Urgent Response Fund for the Auckland region. The funding was for schools and services to hire additional staff to support students and provide ‘catch-up’ tuition.

About this report

Following the implementation of the support package for Auckland students, ERO undertook an evaluation of the three Te Kura programmes aimed at supporting young people in Auckland to achieve their NCEA aspirations. It was important to learn how effective the programmes were, to inform future responses. To do this we asked three questions.

- Who did the programmes reach?

- What was their impact on student wellbeing, engagement, and attainment?

- What are the lessons for future responses?

ERO collected a wide range of data to understand the impact of the package of support, provided to NCEA students by Te Kura, on student outcomes. ERO spoke to students, parents and whānau, Te Kura teachers and staff, Ministry of Education staff in Auckland and their national office, and ERO staff working in the Auckland region.

The evidence collected included:

- Ministry of Education referral data

- Te Kura enrolment and student usage data

- interviews with Ministry of Education staff in Auckland and Te Kura staff

- interviews with ERO staff working in the Auckland region

- interviews with students enrolled in the Te Kura programmes, their parents, whānau, and support people

- Te Kura Student Well-being Survey data

- NZQA NCEA Credits and Achievements data

- Te Kura Transitions data.

A more detailed description of the data collected is provided in Appendix 1.

ERO is very grateful for the time and input of all those we spoke to while carrying out the evaluation.

ERO worked closely with the Ministry of Education and Te Kura to collect data and gather insights about the impact of the Te Kura package of support. We would especially like to thank Te Kura’s data team who were invaluable in providing us with access to their data and analyses.

The report is divided into three sections.

Part 1 sets out what the impact was on students who enrolled in the three expanded Te Kura programmes. The section looks at the following questions:

- Did the expanded Te Kura programmes reach at-risk students?

- What was the impact on student wellbeing?

- What was the impact on student attainment?

- What was the impact on keeping students engaged in education?

Part 2 sets out what has been learnt about:

- what works in reaching at-risk students

- what works in supporting wellbeing

- what works in supporting attainment

- what works in supporting engagement

- what supports the implementation of urgent response programmes such as these

- supporting disengaged students.

Part 3 provides recommendations about:

- what to do in response to future disruptions

- how to prepare for future disruptions for NCEA students.

Out of scope

The evaluation did not evaluate:

- the efficacy of Te Kura’s programmes overall

- other support for Auckland NCEA students that was not provided by Te Kura

What is Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu ?

Te Kura is a state-funded education provider that offers distance learning for a wide range of learners. Te Kura takes on enrolments from children in the early years all the way up to NCEA tuition. Most teaching is delivered online, though there are opportunities for face-to-face interactions.

Te Kura is New Zealand’s largest school with more than 23,000 students enrolled during the last year. Most of Te Kura’s full-time enrolments come from referrals by the Ministry of Education. These students are usually referred because they have been excluded from school, are not enrolled in a school, or have psychological or psychosocial reasons which prevent them from attending school. More than half of these referrals are Māori learners.

Learners between the ages of 16 and 19, who are not currently enrolled full-time at a school, can enrol at Te Kura without cost. In addition, enrolment may be free for any learner under the age of 19, provided they meet the Ministry of Education’s eligibility criteria. More information about the enrolment criteria can be found online at Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu (Te Kura) Enrolment and Dual Tuition Policy - 2020-go5766 - New Zealand Gazette.

Students that are attending a school can utilise Te Kura to study subjects that aren’t available at that school, provided they meet certain criteria.

Te Kura also enrols adult learners for a small fee.

The Te Kura programmes

Last year three existing Te Kura services were expanded to support Auckland NCEA students to enhance learning opportunities and re-engagement with their learning, following the disruption caused by two Covid-19 lockdowns. The fact that the three programmes already existed helped Te Kura to quickly get them up and running. For example, the Te Kura 400 programme was established within four weeks, with 10 fully staffed teaching locations in the community.

Te Kura 400

The programme was intended to support NCEA students who had disengaged from school and were no longer enrolled at a school, or who were still enrolled at a school but at risk of disengaging (for example, those who had stopped attending school). It was meant to provide sufficient NCEA credits to ensure students were able to continue with their education or transition into employment at the end of the programme.

Te Kura 400 (TK400) was modelled off the Te Kura “Big Picture” programme, though TK400 was funded at a much higher level. The high level of funding allocated to this programme meant that all students were provided with their own device as part of enrolment. It also enabled Te Kura to hire more staff to support students.

Te Ara Pounamu/Big Picture learning

- Full-time learning across the academic year

- Standard enrolment process through the Ministry enrolment policy

- Ministry review referrals every six months

- Regular contact with learning advisor and kaiako (teacher) online

- Opportunity to attend a face-to-face huinga ako/advisory once or twice a week

- Opportunity to attend an online huinga ako/advisory once or twice a week

- Access to Te Kura’s online teaching resources and support

- Opportunities to connect with community experts relevant to student learning plans

- Transition planning and support for students

Te Kura 400

- Full-time learning across Term 4 2020 (and extended to Term 1 2021) for those that needed it

- Rapid enrolment from the Ministry without usual application process/gateway

- Ministry collaboration and oversight throughout the programme

- Regular contact with learning advisor, kaiāwhina and kaiako (teacher) online

- Opportunity to attend a face-to-face huinga ako/advisory up to five days a week with learning advisor and kaiāwhina

- Opportunity to attend an online huinga ako/advisory once or twice a week with learning advisor and kaiāwhina

- 11 extra physical sites available, staffed every day. Locations able to be community specific due to the number of them in place

- Reduced ratios of students to learning advisors

- Access to Te Kura’s online teaching resources and support

- Heightened opportunities to connect with community experts relevant to student learning plans (for example, taster days at MIT)

- Intensive transition planning and support for students and whānau (families)

- Devices provided to all students to enable engagement with online material

The programme had two primary teaching formats: online and face-to-face. Students had access to online resources through the Te Kura website portal. To enable face-to-face teaching, the programme provided several pop-up sites in community venues for students to attend. These were staffed five days a week, and contact times with teachers were flexible. Te Kura also recruited people from the community to fill the role of kaiāwhina, or mentors.

Kaiāwhina were non-teaching kaimahi employed from local communities with skills in building relationships with young people, particularly with Māori and Pacific learners and whānau. Some kaiāwhina had recently graduated and some were experienced. They worked alongside teaching staff at the sites, supporting with technology, learning, offsite experiences, and transition planning. Kaiāwhina received training in Te Kura systems so that they could support students and whānau to navigate the online system. They also worked online and over the phone with students, depending on the needs of each student at the time.

A unique aspect of the programme was that students could be enrolled with Te Kura and remain enrolled at their local school. This is different to Te Kura’s “Big Picture” programme, in which the Ministry of Education requires students be unenrolled from their local school to enrol in.

The programme ran from 12 October 2020 to 16 April 2021.

Targeted Dual Tuition

The programme was intended to support students who were attending their local school but were at-risk of becoming disengaged or who needed additional assistance to remain on their planned NCEA pathway.

Target Dual Tuition provided students online access to Te Kura teachers, and the relevant material to study their target subject. Students continued to attend classes at their usual school but would have time reserved to undertake learning through Te Kura. Schools provided a venue (such as a classroom) for students, and staff to supervise them. Te Kura teachers had responsibility for the academic learning in the class, and helped students develop individual learning plans that built on their prior knowledge. Te Kura also connected with their local networks to develop pathways to future education or employment. While the additional teaching through Te Kura is intended to be flexible and responsive to a student’s learning needs, the pastoral support of the student was to remain the responsibility of the student’s local school.

School leaders could identify students who were struggling to keep up with their schoolwork after the lockdowns and refer them for Targeted Dual Tuition. These students could be otherwise engaged at school but needed extra support or credit opportunities to achieve their NCEA goals by the end of the year.

As Targeted Dual Tuition only ran for Term 4 of 2020, students that required a small number of credits to reach their NCEA goals were identified as the intended target.

Summer School

The Te Kura Summer School programme runs during the summer break between school years. It primarily serves to give students a last opportunity to obtain NCEA credits before the next academic year begins. As part of the Covid-19 response, the enrolment cap increased from 1,000 to 4,000 students.

Summer School is for students who are close to, but have not quite achieved, their NCEA goals. Enrolment was open to students who required 10 credits or fewer to attain a NCEA accreditation or University Entrance. The expanded places were strongly promoted in low-decile schools and communities, as students in these areas were deemed to have an increased risk of not achieving their NCEA goal. The programme requires the student to carry out their learning online during the school summer break.

This report looks at the impact of the three programmes.

Part 1: What was the impact on students?

For students to be successful in their education and achieve their NCEA goals, they need to be engaged in education, have their wellbeing supported, and receive quality teaching.

We collected a range of data to investigate the impact of the Te Kura programmes on student outcomes. These included student enrolment records, NCEA achievement data, wellbeing survey data from Te Kura, and interviews with students, parents and whānau, kaiāwhina, and Te Kura kaiako. This section reports on the impact on student outcomes for each of the three programmes: TK400, Targeted Dual Enrolment and Summer School.

TK400

The expanded Te Kura programmes were launched at the beginning of Term 4 2020. The Ministry of Education targeted the Te Kura programmes towards students most at risk of disengaging from school and whose learning had been significantly disrupted by Covid-19.

The Ministry targeted students in low-decile schools and low socio-economic communities, as they were most likely to have experienced substantial disruptions to their learning following the Covid-19 lockdowns. In particular, there was a focus on reaching Māori and Pacific students as they often experience poorer education outcomes and are underrepresented in tertiary education. The Ministry’s Auckland office referred students already disengaged or at risk of disengaging from schools to Te Kura for the TK400 programme.

The evaluation set out to answer four questions about the TK400 programme:

- Did the expanded Te Kura programmes reach at-risk students

- What was the impact on student wellbeing?

- What was the impact on student attainment?

- What was the impact on student engagement?

a) Did the TK400 programme reach at-risk students?

Of the 400 places available, 193 students enrolled in TK400 throughout the duration of the programme. Nearly half of the TK400 students (88 students) were still in the programme at the end of Term 1 2021. Most of the students who left the programme before it ended returned to a mainstream school. Students were referred to TK400 by the Ministry of Education’s Auckland office from individuals and groups who were trying to support students. These included the Ministry’s attendance service, church and community networks, school leaders, and parents. Many of these students were functionally disengaged from schooling, with some having been absent from school for over a year.

“…we were accepting referrals from attendance services, schools, parents. Referrals from our own internal teams, education advisors within the Ministry - who often are dealing with trying to support individual students.” - Ministry of Education

The TK400 programme was successful in reaching at-risk students. The students enrolled were more likely to live in low socio-economic households and identify as Māori or Pacific. A total 193 students were enrolled in TK400, filling approximately half of the 400 places set aside. This enabled the programme to be extended. TK400 ran throughout Term 4 of 2020 and Term 1 of 2021.

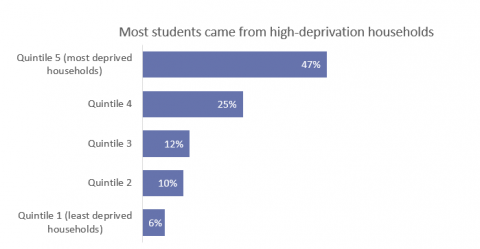

Nearly half of the students in the TK400 programme were from the 20 percent most deprived communities. Only 6 percent of students in the programme were from the 20 percent least deprived communities.

Figure 2, Percentage of TK400 students who live in the most deprived communities in New Zealand

Bar graph. Title reads "Most students came from high-deprivation households". It then has five bars. The first one reads "Quintile 5 (most deprived households)" and the percentage in the bar graph is 47%. The second bar reads "Quintile 4" and the percentage in the bar graph is 25%. The third bar reads "Quintile 3" and the percentage is 12%. The fourth bar reads "Quintile 2" and the percentage in the bar graph is 10%. The final bar is titled "Quintile 1 (least deprived households) and the percentage reads 6%. The graph shows that most students came from high deprivation households.

Note: Community deprivation is measured using the New Zealand index of deprivation

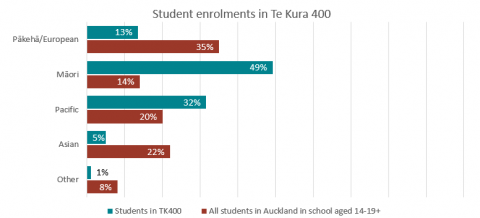

Nearly three-quarters of students who enrolled in TK400 identified as Māori (49 percent) or Pacific (32 percent). Around 10 percent of students identified as New Zealand European. A small number of students identified as Asian or MELA (other). In comparison, Māori students make up 14 percent of all students in Auckland aged 14 years or older, with Pacific students accounting for 20 percent overall.

Figure 3, Auckland students enrolled in Te Kura 400 compared with Auckland school students aged 14-19, by ethnicity

This image is a bar graph. The title reads "Students enrolments in Te Kura 400". There are five sets of bars in the graph. The comparative bars for each set compare "Students in TK400" and "All students in Auckland school ages 14-19+". The first set of bars shows that 13% of students enrolled in TK400 were Pākehā/European and 35% of students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Pākehā/European. The second set of bars shows that 49% of students enrolled in TK400 were Māori and 14% of students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Māori. The third set of bars show that 32% of students enrolled in TK400 were Pacific and 20% of students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Pacific. The fourth set of bars show that 5% of students enrolled in TK400 were Asian and 22% of students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Asian. The final set of bars shows that 1% of students enrolled in TK400 were Other and 8% of students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Other.

Half of TK400 enrolments were from students who were not enrolled in a school, which shows that the programme was successful in reaching students who had completely disengaged from education and were no longer part of a structured schooling environment.

Some students were still enrolled at their local school but had stopped attending. One student told us that:

“It [Covid-19] has scared my family. It has affected my (NCEA) level 2. My family has not allowed me to go back to school.” - Student

However, some students who came into the programme had disengaged from school prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. A Te Kura teacher/mentor told us that:

“… some kids haven’t attended school anywhere from a year to three years. I think we offered a safe and inclusive environment that allowed our kids to open up and be themselves again.” - Kaimahi

b) What was the impact on student wellbeing?

Wellbeing was a significant focus of the TK400 programme, and one of the key outcomes for the students enrolled.

One of Te Kura’s teaching staff who was involved in the TK400 programme shared that “The process for engaging with at risk students needs to be focused more on their wellbeing than on their academic results. Once they feel affirmed, secure, and accepted everything will fall into place.” - Kaiako/Kaimahi

The main impacts on student wellbeing were that:

- parents and whānau told us that the TK400 programme was having a positive effect on their child’s wellbeing

- the wellbeing of students in the TK400 programme was positive

- Te Kura staff told us that they observed an increase in students’ confidence in learning as they progressed in the programme.

Parents and whānau told us that the TK400 programme was having a positive effect on their children’s’ wellbeing

The parents and whānau of 20 TK400 students were asked about the impact the programme was having on their child. Almost all of them said that it was having a very positive impact on the wellbeing of their child. Many of them talked about their child’s increased confidence, despite the adversity their child had experienced.

“She has become responsible for her own learning, and it has boosted her confidence. It is too easy for students to lose their way or give up when it gets overwhelming, but Te Kura had kept her on track.” - Whānau voice

“This programme [TK400] has been so encouraging for our son… it has helped him gain so much confidence, our son is autistic. So this was the only option, but it has helped re-engage, helped his credits for NCEA and the hours are fantastic!! He has achieved so much in a small amount of time.” - Whānau voice

The wellbeing of students in the TK400 programme was positive

Te Kura ran a student wellbeing survey for enrolled students. Nearly half of the students in TK400 completed the survey shortly after they started. The responses from students in TK400 were very similar to other students enrolled at Te Kura.

Most TK400 students said that they were feeling positive, that they could keeping going when things got tough with their learning, had people to turn to for support, and felt their culture was being valued.

The majority of TK400 students, who completed the Te Kura wellbeing survey, said they felt they could go on learning when things get tough on occasion or all the time. Nearly all the students felt safe in their community and thought they could access help if they needed it. Finally, nearly all students indicated that they felt confident that they could learn, at least some of the time.

TK400 students’ wellbeing was relatively high, and they even responded more positively to some questions than other Te Kura students. This is especially encouraging as these students were particularly impacted by Covid-19 lockdowns.

When asked whether they agree with the statement "I believe I can go on learning when things get tough":

- 47% of TK400 students said "all or most of the time", compared with 45% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "all or most of the time"

- 47% of TK400 students said "on occasion", compared to 47% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "on occasion"

- 7% of TK400 students said "not at the moment", compared to 9% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "not at the moment"

When asked whether they agree with the statement "I feel safe in my community and I know how to seek help if I need it":

- 74% of TK400 students said "all or most of the time", compared with 65% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "all or most of the time"

- 27% of TK400 students said "on occasion", compared to 32% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "on occasion"

- 0% of TK400 students said "not at the moment", compared to 3% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "not at the moment"

When asked whether they agree with the statement "I feel confident I can learn and get better over time":

- 67% of TK400 students said "all or most of the time", compared with 64% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "all or most of the time"

- 33% of TK400 students said "on occasion", compared to 32% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "on occasion"

- 0% of TK400 students said "not at the moment", compared to 3% of the rest of Te Kura students who said "not at the moment"

To supplement the data collected through Te Kura’s wellbeing survey, we got feedback from fourteen TK400 students about their experience of the TK400 programme. A list of the questions can be found in the appendix. The majority of TK400 students, who provided us with feedback, reported a very positive experience in the programme. One student told us:

“I have felt very happy. I thought I would never get a second chance from school. I have felt very supported.” - Student

Most students also told us about how they were making new friends by attending one of the community sites.

“It’s been nice meeting and making new friends.” - Student

Te Kura staff told us that they observed an increase in confidence in learning as they progressed in the programme

Kaiako and kaiāwhina (teachers and mentors) in the TK400 programme also provided us with feedback about the programme. A list of the questions can be found in the appendix. Most of the respondents told us that they could see a strong positive impact on the students in their care. One of the key impacts, reported by kaiako and kaiāwhina, was the increased confidence among students as they got involved, both academically and socially in the programme, which helped with their engagement:

“The impact the expanded Te Kura opportunities has had on the most at risk ākonga is that they have opened up, become more confident, regained belief in themselves and what they can achieve, discovered new interests, gained understanding, security, and new friends.” - Kaiako

“The stand outs have been seeing the confidence grow in the ākonga, their smiles and how happy they are to ask questions when they are unsure. They are happy to come to the huingā ako and now feel like they are valued and someone has their back, who will help them reach their goals whatever they may be.” - Kaiako

c) What was the impact on student attainment?

The focus of the TK400 programme was to support students to reengage in education and their NCEA study. While TK400 was not focused on achieving NCEA credits, around one in five (18 percent) students gained at least one NCEA credit. The achievement was similar to a matched group of Te Kura’s full-time students who live in similar communities with the same socio-economic status, over the same duration of enrolment (around two terms). A description of the methodology can be found in Appendix 1.

Though only a small number of students obtained credits, the impact was significant for those that did. Students told us:

“Taking part in the Te Kura programme has helped me a lot with getting back on track with my learning to gain my UE credits. I feel more engaged with my learning and am getting the extra support I need.” - Student

Another student shared:

“[Without TK400] I don’t think I would be able to gain my UE credits and I would have no interest in my school work.” - Student

A student’s whānau told us:

“… She [daughter] had done stuff through AGGS – but hadn’t sent it off. She was scared it wasn’t good enough. She needed someone other than her mother who she could trust to look at the work and say you can this time – that’s where Te Kura comes in.” - Whānau

“I felt so supported by my subject teachers; They were really encouraging and made it really easy for me to study and complete my exams at school.” - Student

We asked students what they thought they would have done, had TK400 not been available. In general, they felt that they would have been more negatively impacted without the opportunity presented by the programme. Students told us:

“There wouldn’t have been any learning if I didn’t come here, I would do nothing.” - Student

“I would have been another Māori lost in the system. The Te Kura programme gave me motivation because of how supportive they are.” - Student

When we interviewed parents, they also identified positive outcomes in their child’s education.

“It [TK400] kept him in some classroom environment. There was consistency in his learning which is good. He has also met some new people.” - Whānau

d) What was the impact on student engagement?

Students need to be engaged in their learning to be successful. If a student becomes disengaged, they are at risk of not continuing with their education. TK400 was highly successful at engaging students and supporting them to achieve their education goals. Almost all (96 percent) of the TK400 students had a transition plan for when the programme finished. Three-quarters of students returned to school or decided to continue their education with Te Kura. One-in-ten students (11 percent) had enrolled in a tertiary institution and another 10 percent had found a job.

The most common destination for TK400 students who remained enrolled in a school was to return to school (58 percent). Whereas the most common destination for TK400 students who were not enrolled in any school was to continue their education with Te Kura (58 percent).

The TK400 programme appears to have helped students to engage in their learning again. For some students it was a format that really worked. One parent told us:

“Please keep the programme on! It has helped him a lot. The teachers are fantastic, and he likes learning so much now. Please let the programme continue for 2021 and longer.” Whānau

Te Kura teaching and support staff also saw positive impacts on the students in their care:

“We’ve been able to observe real change in our ākonga. From quite negative attitudes towards anything to do with school and learning to now wanting to engage, interact and learn.” Kaimahi

The programme also appeared to be helping students think about further education:

“My son really liked the [polytech] visit and is interested in engineering now. Thank you Te Kura for offering him this help…” Whānau

Targeted Dual Tuition

For the Targeted Dual Tuition programme, the Ministry and Te Kura approached several schools serving Māori and Pacific communities and those in areas that were economically disadvantaged. Students would continue to attend classes at their usual school. Schools would need to reserve time for students to undertake learning with Te Kura, as well as provide a venue (such as a classroom) and staff to supervise them.

There were only 44 students enrolled in the Targeted Dual Tuition programme. Almost all of these students came from just four schools. Even within these four schools, this was a small percentage of the overall roll. It was not known what the projected uptake of this programme would be, but it was clear that the total roll of 44 students was lower than all parties had anticipated.

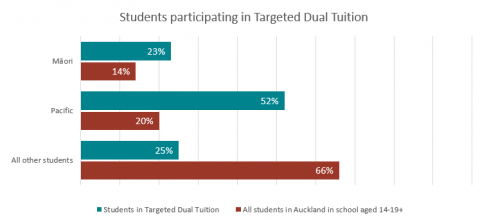

The Targeted Dual Tuition programme reached very few at-risk students. Over half of the students who took part identified as Pacific and just under a quarter identified as Māori. Pacific students were over-represented in the programme (52 percent), compared to all Auckland students aged 14 years or older, where Pacific students make up only 20 percent. This representation demonstrates the programme was reaching its target audience, but in a smaller quantum than intended.

Figure 7, Auckland students participating in Targeted Dual Tuition compared with Auckland school students aged 14-19, by ethnicity

A bar graph with three sets of bars. The title reads "Students participating in Targeted Dual Tuition". The bars compare "Students in Targeted Dual Tuition" with "All students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+". This first set of bars shows that 23% of students in Targeted Dual Tuition were Māori and 14% of all students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Māori. The second set of bars show that 52% of students in Targeted Dual Tuition were Pacific and 20% of all students in Auckland in school aged 14-19+ were Pacific.

The evaluation set out to answer four questions about the Targeted Dual Tuition programme. However, the small number of students who enrolled in Targeted Dual Tuition meant there was insufficient data to judge the impact on student wellbeing, attainment and engagement.

Summer School

The additional places in Summer School were available to all Auckland NCEA students, who could decide if they needed to enrol in the programme. A total of 695 Auckland students enrolled in Summer School, with the total number of Summer School enrolments reaching nearly 2000 across New Zealand. The total number of students enrolled in 2020 Summer School was similar to previous years.

The evaluation set out to answer four questions about the additional places in Summer School for Auckland students.

- Did the expanded Summer School places reach at-risk students?

- What was the impact on student wellbeing?

- What was the impact on student attainment?

- What was the impact on student engagement?

a) Did Summer School reach at-risk students?

Enrolment in Summer School by Auckland students increased during November 2020 well before the term ended and final results were in. More students were enrolling at this early stage than is typical for Summer School. The result was a higher number of students enrolled at the end of Term 4 2020 compared to previous years. This indicates that students may have dealt with the uncertainty caused by the Covid-19 pandemic by making sure they could access additional support, should they need it, once the normal school year ended.

Students enrolled in Summer School earlier in the year, compared to previous years. However, by the time enrolments closed, there was a similar total number of students registering for summer school in 2021, compared to 2020.

Figure 10 shows that two-thirds of Summer School students identified as New Zealand European, compared to 12 percent of students who identified as Māori and 20 percent as Pacific. The ethnic mix of students in Summer School is similar to all Auckland students aged 14 years or older (NCEA students).

While TK400 and Targeted Dual Tuition were composed of targeted students, Summer School reached a group of students who were more ethnically similar to all Auckland students aged 14 years or older. Summer School students are likely to be less at-risk of achieving their NCEA goals but have self-identified as needing more support.

The evaluation heard of several reasons why, by the end of Term 4, students did not need Summer School to achieve their NCEA goals:

- Auckland students received additional NCEA changes to support them.

- Auckland students could earn additional learning credits and required fewer credits to get Merit or Excellence endorsements.

- Schools went above and beyond to support students disrupted by Covid-19 (Education Review Office, 2021).

- Additional government funding was made available for schools to support students impacted by Covid-19, such as teacher aides and mentors.

- University requirements were relaxed.

We heard from some of the students we interviewed that they had received discretionary consideration after they had already begun Summer School. Students can apply for discretionary consideration if they have experienced unforeseen or unavoidable circumstances, which might allow them to enrol at university even without meeting the usual requirements. This was expanded following Covid-19, and more students became eligible due to the disruption. The students told us that, after they were given entry to their chosen university, they no longer felt that engaging in Summer School was necessary.

One student told us that:

“… I did not need Summer School. Though I did not pass the year I am super happy with how my university of choice has gone about this and I was offered provisional entry.” - Student

b) What was the impact on student wellbeing?

ERO created a short survey for Summer school students and their kaiako (teachers) to provide their experience of summer school. The questions they were asked can be found in the appendix. Students did not talk about any wellbeing benefits from participating in summer school. Students told ERO that the main benefit of the Summer school programme was obtaining sufficient credits to get University Entrance (this will be discussed further in the attainment section below).

c) What was the impact on student attainment?

The Summer School programme was designed to support students to gain additional credits to help them achieve their NCEA goals. Students who chose to attempt NCEA credits in Summer School were successful. Summer School students told us that the main purpose for enrolling was to obtain sufficient credits to get University Entrance.

The focus on University Entrance was visible in the credit opportunities taken. Most students enrolled for literacy and numeracy subjects. The most common subject taken at Summer School was NCEA Level 3 English.

Approximately 40 percent of all the students enrolled in summer school for the 2020 academic year attained NCEA results while enrolled with Te Kura. This is a slight decrease from 48 percent of all Summer school students in the 2019 academic year. However, more than 90 percent of standards submitted to Te Kura from Summer School students received a result of achieved or higher. This is a similar pass-rate to previous academic years.

d) What was the impact on student engagement?

The programme appears to have engaged those students who participated in the programme. Nearly all students (over 90 percent) who participated in the programme achieved at least one NCEA credit. This suggests that they were engaged. One student told us about their engagement in summer school, giving credit to their Summer School teacher saying:

“he was so helpful with the extensive advice he gave to help me pass the internals, and was, quite honestly, the best teacher I have ever had.” - Student

Not all students who were enrolled chose to participate in Summer School. It is likely that in many cases these students did not need to engage as they already had what they needed to go forward.

Part 2: Lessons learnt

The evaluation provided some clear lessons about supporting students in response to learning disruptions. This section outlines some practical actions to consider when working to support schools following a crisis. It sets out what worked in:

- reaching at-risk students

- supporting student wellbeing

- supporting student attainment

- supporting student engagement

- implementing the urgent response programme

- supporting disengaged students.

2a) What works in reaching at-risk students?

Despite the challenges of reaching at-risk students following the Covid-19 lockdowns last year, we found that a number of activities had helped to reach students. We also uncovered some lessons for how to improve targeting at-risk students in the future. These key lessons are listed below.

- It is important to get students enrolled as quickly as possible.

- Introducing additional support towards the end of the school year may make it harder for schools and students to participate.

- Face-to-face meetings with students and school leaders help to reach students most in need.

- Targeting specific schools helps to reach students with the most need.

- Schools prefer to support their own students with their own responses where possible.

- It is important to allow enough time to contact students and schools.

- A lack of knowledge about both the provider and the programmes may have discouraged some schools from participating.

- Existing relationships between the provider and schools helps with enrolling students.

It is important to get students enrolled as quickly as possible

Introducing the TK400 programme during Term 4 meant that students needed to be enrolled as quickly as possible, to ensure students gained the maximum benefit. The Ministry of Education and Te Kura told us that the usual referral and enrolment process would take too long and therefore decided to revamp the process. Staff at the Ministry of Education and Te Kura collaborated to develop a more responsive gateway into the programme. Ministry staff in Auckland told us that they overhauled their referral system entirely, developing a set process that ensured students were referred to Te Kura within 24 hours. They also told us about how Te Kura also adjusted their enrolment process:

“Te Kura set up a process for 24 hours to get the student enrolled and then another couple of days for the teacher to get in contact and start getting the subject and the learning started.” - The Ministry of Education

The result of these changes was that TK400 students could be brought on board the programme in a couple of days.

The Ministry of Education’s referral team in Auckland told us that they knew from experience that students and whānau, who were looking for support after Covid-19, may become discouraged if they were not quickly enrolled in the TK400 programme.

The Ministry referral team said that the quicker referral and enrolment process reduced the number of students who did not end up enrolling with Te Kura after being referred. However, it also meant that less information about students’ learning needs and goals were provided to Te Kura. Much of this information had to be gathered once a student had started the programme. Despite this trade-off, Te Kura staff told us they were supportive of the changes to the referral process.

Introducing additional support towards the end of the school year may make it harder for schools and students to participate

The Targeted Dual Tuition programme may have been implemented too late in the school year to allow schools and students to participate.

The Targeted Dual Tuition programme was set up to run from early in Term 4 2020 through to NCEA exams, and schools were made aware of the programme from the beginning of Term 4. The Ministry of Education told us that there was not sufficient time for schools to build an understanding of the benefits of the programme, or to decide which students would benefit the most.

Face-to-face meetings with students and school leaders help to reach students most in need

The project leaders at Te Kura and the Ministry of Education told us that face-to-face meetings with students and school leaders was the most effective way to explain what types of students would benefit from enrolling in the TK400 programme. They said that many of the referrals they received came from the schools they were able to talk to in person.

Targeting specific schools helps to reach students with the most need

To help the TK400 programme reach students with the most need, the Ministry approached groups of schools, which they referred to as tranches of schools.

“…We defined [the tranches] according to mainly need, I guess, Decile 1, high, Māori, Pasifika, those kinds of criteria where we saw there was going to be high need. [or] were predicting there would be high need.” - Ministry of Education, Auckland.

Targeting particular schools helped reach at-risk students. A high proportion of students in the TK400 programme were Māori and Pacific students from low socio-economic communities.

The Ministry also told us that another reason they approached specific schools was a concern about receiving too many referrals.

“…we were a bit worried that we could be inundated with referrals from schools.” MOE Auckland

Schools prefer to support their own students with their own responses where possible

Many schools spoken to by ERO in 2020 were rolling out strategies and support to engage students after the disruptions created from the lockdowns (Education Review Office, 2021). Schools had expanded their capacity to support at-risk students, and ERO review staff told us teachers were keen to support their own students. Operational staff at both the Ministry and ERO indicated to us that schools may have been reluctant to enrol students in the TK400 programme as it would take them out of school.

We also heard that some schools were able to provide their own support, using the government’s Urgent Response Fund for schools, to respond to the increased needs of students caused by the Covid-19 disruption. The Ministry of Education told us that the fund for the Auckland region had received over 1,600 applications by December 2020. Schools used the funding to hire more teacher aides, mentors, and counsellors, and to provide additional tutoring for students.

It is important to allow time to contact students and schools

The Ministry of Education told us that students who had stopped attending school were difficult to reach. Staff had to rely on contact details provided by schools, and the students’ parents or whānau did not always respond to phone calls or emails. Te Kura staff also told us that contacting parents and whānau by phone was more reliable than using email, but did take more time.

Ministry staff were also able to use the Attendance service as a referral gateway for those students who were not attending school.

The Ministry told us that schools in Auckland were busy responding to Covid-19 and were already having to deal with a large volume of information, such as keeping up with the different requirements of Covid-19 Alert Levels. ERO found that school leaders in low decile schools were especially busy because they were also supporting their local community (Education Review Office, 2021).

A lack of knowledge about the provider and the programmes they were running may have discouraged schools from participating

Schools may have been discouraged to enrol their students in the programmes being provided by Te Kura because:

- some schools had a negative perception about Te Kura’s programmes

- there was confusion about how the programmes would work in a school

- there was confusion about which students would benefit from enrolling

- there was concern that the some of the support was too short to benefit students.

There may have been a negative perception of Te Kura among schools, which could have led to a reluctance to refer students to the TK400 programme. Across several of the workshops with operational staff from Te Kura, the Ministry, and ERO, it was suggested that there were some underlying concern among some school leaders and teachers about the quality of the programmes provided by Te Kura. We also heard from Ministry staff that in some cases schools thought that Te Kura’s involvement with their school could negatively impact their reputation.

School leaders and teachers were unclear about what their role was in the Targeted Dual Tuition programme. The intent was that Te Kura would supply the teaching and learning resources (online), and that schools would ensure that there was a venue, and provide students with pastoral support.

The exception were schools that already used Kura to supplement their taught curriculum. These schools had a better understanding of how the Targeted Dual Tuition programme would work in their school. However, the majority of schools remained confused about the programme.

Ministry staff told us that “This was new, the Targeted Dual Tuition – maybe not for some schools that already did it, the smaller schools that already had that opportunity. But for others, it was something very new. So they had to learn about it and get set up with Te Kura to understand how it worked.” Ministry of Education, Auckland

Ministry of Education staff told us that some schools were additionally confused about how the Targeted Dual Tuition programme differed from Te Kura’s online teaching resources. Earlier in 2020, Te Kura had responded to Covid-19 by allowing teachers to access their online teaching resources, and for students to be able to undertake some of these independently – without enrolling in Te Kura. We were told that in some cases it was not understood what was different about the new offering.

School leaders were not clear on what the Targeted Dual Tuition programme would achieve for the students who enrolled. This impacted which students they chose to refer to the programme. We were told by kaimahi and whānau that some students needed more NCEA credits than could reasonably be achieved in a single term. We were also told that some of the students enrolled need more support than could be provided by the Targeted Dual Tuition programme. Where possible, these students were transitioned to TK400. This may have contributed to fewer students enrolling in the Targeted Dual Tuition programme when it became apparent the programme could not provide wrap-around support for students.

A Te Kura project lead shared their reflection on what could be changed in the future, saying;

“I think it's really important for those students at the school that it's really clearly spelled out for the schools, next time… [So they will know] which students will get the maximum benefit from this [programme] and that it's realistic. Because, you know, it was unrealistically giving students false hope.” - Te Kura project lead

The Ministry of Education told ERO that the Attendance service in Auckland was reluctant to enrol students in the TK400 programme because they felt that the TK400 programme may be too short (when originally planned to only run in Term 4 2020). The Attendance service was looking for more longer-term solutions for disengaged students. They were concerned that students may have to be placed into another programme once TK400 had finished, and that the programme may not meet the needs of students. However, we found that majority of TK400 students successfully transitioned into further education, training, or employment by the end of the programme (Term 1 2021), and as such the programme was an important bridge.

Existing relationships between Te Kura and schools helps with enrolling students

Existing relationships between Te Kura facilitators and school leaders helped to get additional support to students. A Te Kura project lead told us they were able to approach a principal they knew and let them know “…hey, we’re here, we're available to support what can we do to support you and your tamariki.”

Te Kura project leads told us that more than three quarters of the students who enrolled in the Targeted Dual Tuition programme came from schools that have had a history of working with Te Kura. These schools had already been using Te Kura to offer additional subjects such as particular languages. School leaders who were already working with Te Kura found it easier to understand how the programmes would work in their school.

2b) What works in supporting wellbeing?

An important part of engaging students in learning is their wellbeing. Students who enjoy their learning environment, who feel like they belong and are listened to, are more likely to stay engaged in their learning and put in more effort (Hayes, Down, Talbot & Choules, 2013, Big Picture Education Australia: Experiences of students, parents/carers & teachers). This is especially important for students who have stopped attending school and are struggling to reengage in their learning. We found four key learnings from the Te Kura package of support that supported student wellbeing.

- Face-to-face meetings helped students connect with teachers and peers.

- Small groups can make students more comfortable.

- Organising face-to-face meetings at a time and location that suited students was important.

- Availability of a back-up plan, like Summer school, can help to reduce anxiety.

Face-to-face meetings helped students connect with teachers and peers

Students told us they appreciated the opportunities to connect with other people in the programme. When asked what taking part in TK400 meant for them, one student told us that it meant he was:

“… able to do something rather than staying at home. It was helpful and encouraging.” - Student

One parent told us about the importance of the face-to-face component of the programme. When asked about what they thought their child might be doing if not for TK400 they said:

“My son would probably be at home, not learning, not even online – he needs help like this, like what you are doing here (in the project at the venue)” - Parent

From the number of students that talked about the social benefits of TK400, we can see that the face-to-face environment enabled students to re-establish valuable social connections.

Small groups can make students more comfortable

The classrooms students attended were much smaller than traditional classrooms. Students and their whānau identified this as an important element that helped to make the environment more comfortable.

“… [TK400] gave me an opportunity to learn again. It helped with social anxiety in school because it was a smaller learning environment. I felt more comfortable and safer. I liked the flexible hours Te Kura offered….” - Student

Smaller class numbers also helped enable kaiako and kaiāwhina to spend time with students and get to know them as individuals.

“I am happy to come to Te Kura rather than school because it is a small class, and my Kaiāwhina can help me one to one” - Student

Organising face-to-face meetings at a time and location that suited students was important

Across multiple focus groups we heard that the face-to-face meetings worked for students because these meetings were at flexible times and at neutral locations. Students were able to engage more on their own terms. We heard that this allowed students to fit these meetings around their lives at a time the suited them.

Te Kura teaching staff observed the positive outcomes of giving students more agency over the hours they worked. They told us that they believed that maintaining flexible hours enabled the programme to be even more accessible.

“The flexibility of being able to learn asynchronously has also had an incredibly important impact.” - Kaiako.

Availability of a back-up plan, like Summer School, can help to reduce anxiety

The availability of the Summer School programme may have helped to reduce anxiety among Auckland NCEA students. Announcing additional places gave students confidence that there was a back-up option in case they did not get sufficient credits to achieve their NCEA goals. Both the lockdowns (national and Auckland) produced an increase in Summer School enrolments.

Te Kura told ERO that more than half of the students enrolled in Summer School did not engage in any learning, which may suggest they were able to achieve their NCEA goals during the school year. Some students told us that they had enrolled in Summer School to ensure they got University Entrance but had already been accepted onto a course, so chose not to engage in Summer School. This evidence suggests that Summer School may act as an insurance policy for students who are uncertain if they will get the NCEA attainment they need to transition into tertiary education.

2c) What works in supporting attainment?

The students enrolled in TK400 were all at different points in their education journey. The small groups of students in TK400 made it easier for Te Kura staff to understand the needs of the students and to individualise the learning programme to each student. One of the teachers told us:

“In most cases these are incredibly motivated young people who just needed that little bit of extra support and a pedagogy based in getting to know them first as people, not just as a number or as a ‘student’.” - Te Kura teacher.

2d) What works in supporting engagement?

Returning at-risk students to learning following a significant disruption is critical. Students told us that the TK400 programme had been a positive experience and helped them rebuild their confidence in their own abilities, leading to a sense of hope and reengagement in their learning.

TK400 students told us that the following factors encouraged them to engage in their learning:

- using venues not associated with a school

- flexible hours, i.e. students could do their work at a time that suited them

- no school uniform.

TK400 teaching staff told us that they were able to support students to engage in the programme by developing meaningful relationships. Teachers were able to find out what students wanted to achieve and what their plans were after the TK400 programme finished. The teachers used this information to make students aware of the opportunities they had in front of them. We were told that prior to the programme, some students did not know about the career pathways available to them through education.

2e) What supports the implementation of urgent response programmes such as these?

The focus of this evaluation was about the impact of the additional support provided to NCEA students and whether the support package could be used in the future to support students following a crisis. In undertaking the evaluation, we learnt some lessons about how to successfully deliver the support packages to students and schools. We found that the key things to consider when developing an urgent response programme were:

- make sure schools are not too busy when you roll out a programme, such as during student exams

- programmes that require partnership can take time to become established

- being aware of how the programmes will interact with other supports being provided to students

- not overloading schools with too much information

- keep communication clear and simple

- established relationships lead to better results.

Make sure schools are not too busy when you roll out a programme, such as during student exams

It is important to consider when in the school year the intervention is to be rolled out (for example, at the beginning or end of the school year). The success of an intervention may depend on what is going on in the school at a given point in the year, particularly for NCEA students. Later in the year, secondary schools are focused on credit examinations and may find external programmes less attractive.

Programmes that require partnership can take time to become established

It is important to consider how long it will take to set up a support programme before beginning to roll it out in schools. School leaders need enough time to understand how an intervention will work in their school and what kind of support it can offer their students. Programmes that require schools to partner with a provider will need extra time, to allow all parties to develop an understanding of their roles and expectations. This will also be impacted by the time of year, as there is limited time available by Terms 3 and 4.

Be aware of how the programmes will interact with other supports being provided to students

It is important to consider how the intervention aligns with other support packages being introduced. The mix of support packages available will likely impact on the uptake of individual programmes. This is particularly important if a targeted uptake is necessary to make the programme worthwhile. In addition, while providing a range of supports gives schools and students options, schools clearly show a preference for supporting their own students.

Don’t overload schools with too much information

School leaders will have a lot of information to digest following a crisis. Consider how much information school leaders will need to understand in order to support a new programme. In a crisis, too much information can be confusing and may make school leaders more stressed. Information overload is more likely in schools who are having to support more disadvantaged communities.

Keep communication clear and simple

It is important that schools understand how a programme will support their school, students, and whānau. Ensure schools understand how a support package differs from other support being offered (for example, what students would benefit the most) to avoid confusing schools. Schools who are confused about a programme are unlikely to help promote it to their students, and whānau. It can help if the school already knows you or is familiar with the type of support being offered. Where possible, it is sensible to use methods appropriate to the cultural context of the school.

Established relationships lead to better results

Schools are more likely to respond and participate when they are contacted by someone or a group they already know and trust. This will make it easier to get them the information they need and to make contact with the right people in the school.

2f) What we learnt about supporting disengaged students

TK400 was successful in keeping NCEA students in education and getting them back into education. This included reengaging students who had been out of school for several months, as well as students who were still at school but considered at-risk of dropping out.

The evaluation found that the following elements contributed to successfully reengaging students following disruptions caused by Covid-19:

- Face-to-face meetings help to establish relationships between students and teachers

- Teaching staff being able to get to know each student

- Small classroom numbers

- Neutral locations

- Flexible attendance hours.

Face-to-face meetings help establish relationships between students and teachers

It is important to establish relationships between students and teachers to promote and maintain engagement (Education Review Office, 2020, Learning in a Covid-19 World: Supporting Secondary School Engagement). The evaluation found that this was especially important in the context of the lockdowns the country experienced in 2020. We heard that this was most effective when it was done face-to-face for Auckland. Some students had become significantly disengaged and had not attended school for a significant period of time (up to three years in some cases).

Teaching staff being able to get to know each student

Meaningful relationships in education can support students’ sense of belonging, which helps promote engagement. (Center for Supportive Schools, 2018, Peer group connection high school: A cross-age peer mentoring and high school transition programme)

Teaching staff were able to focus on the social aspects of learning. They also built on foundational knowledge that would equip students to achieve academically in the future. This was further supported by the addition of kaiāwhina (pastoral support staff) in the classroom. Kaiāwhina were recruited from the local community to support and mentor students and had a good understanding of the students’ lives. Kaiāwhina were not part of the education system. This was reported as important, as many students have had a negative experience with education and having someone on their side proved invaluable for rebuilding that relationship and establishing trust.

Small classroom numbers

Small groups were effective for these highly disengaged students. This evaluation found that the impact of this was twofold. It meant that teaching staff and mentors were able to spend a substantial amount of time with individual students. It also meant that students’ anxiety was alleviated and confidence in relearning re-established. For many students, the classroom had become a daunting place and the low numbers helped make that more manageable for them.

Neutral locations

Contact time with teachers was not held on school grounds or in the home, instead it was held at community sites such as local libraries. Many at-risk students have had negative experiences in school. We heard that neutral locations helped to avoid these associations and provided a platform with which to successfully engage with students. Basing support in the local community made it easier for students to participate.

Flexible attendance hours

In TK400, students were able to structure their learning around their own needs. We heard that onsite classes started at 10am, which was an easier time for many of the teenagers enrolled. Giving students agency to manage some of their time alongside their education resulted in stronger engagement.

In conclusion

What we learnt about supporting disengaged students aligns closely with the evidence about what helps to get students back into learning.

The experience of these Auckland students can help inform how other students could be supported following a disruption to their education and learning. The following section sets out our recommendations for supporting NCEA students following disruptions in the future.

Part 3: Recommendations

This report has looked at the evaluation of the Te Kura package of support for Auckland NCEA students introduced at the beginning of Term 4 2020. The package of support was designed to support students whose learning was disrupted due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It was targeted at students who had disengaged from education or needed some additional help to achieve their NCEA goals.

The evaluation looked at how successful the Te Kura support package was in supporting NCEA students, and whether the government should consider repeating the programmes in the event of future disruptions. It also looked for changes that could be made to the package that might better support students.

From the evaluation, ERO has developed the following recommendations for the Ministry of Education, in order to support NCEA students looking at:

- what can be done to help prepare for future disruptions

- what can be done in response to future disruptions.

3a) To prepare for future disruptions for NCEA students

Unfortunately, in the challenging context of Covid-19 future disruptions remain possible. On the basis of this evaluation, to prepare for future disruptions to NCEA students ERO recommends the Ministry of Education:

- maintain targeted programmes which can be quickly scaled up when needed

- establish relationships now with schools who may need additional support following a crisis or have students who may need the support.

Maintain targeted programmes which can be quickly scaled up when needed

In response to Covid-19, an existing programme (Te Kura ‘Big Picture’) was able to be quickly expanded upon and redeveloped into the TK400 programme seen in this evaluation. The TK400 programme allowed students to stay enrolled with their school while they participated in the programme. The majority of these students returned to school when they left the TK400 programme. It would have been very difficult to set up this programme from scratch in time.

ERO recommends that the Ministry of Education consider maintaining a programme that works alongside schools to help reengage students every year. The programme can then be quickly expanded to support a larger group of students following a crisis like Covid-19.

Establish relationships now with schools who have students who may need additional support

We found that the programmes in this evaluation were better understood in schools that had existing relationships with the providers. Schools that were familiar with Te Kura found it easier to understand how the programme would work in their school and the types of students who would benefit from taking part. These schools were more willing to participate and encourage students to enrol in the programmes.

To help prepare for future disruptions it is worth considering contacting schools with a high proportion of at-risk students now, to make it easier to get them the support they need following a future disruption to student learning. Schools will also be able to outline what support their students are likely to need, which can be used to tailor programmes to support students in the future.

3b) In response to future disruptions for NCEA students

On the basis of this evaluation, ERO recommends the Ministry of Education do the following to support NCEA students:

- Put in place (or scale up) targeted programmes for learners who are at risk or who have disengaged from school.

- Make sure there are back-up options, like Summer School.

- Make sure schools can support students in school as well as providing options for students to be supported outside their school.

- Only deploy programmes that require schools to partner with external providers when the benefits to the school and its students are clear.

Put in place (or scale up) targeted programmes for learners who are at risk or who have disengaged from school

A programme focussed on at-risk learners can have a positive impact. TK400 has shown itself to be a successful initiative in re-engaging at risk learners. These types of programmes can form a key part of any response following significant disruption to schooling (for example, the Covid-19 pandemic or a natural disaster).

The majority of students enrolled in TK400 transitioned back to school, continued to be enrolled in Te Kura, or enrolled in a Tertiary course. A small number of students transitioned into employment.

Many students talked positively about the support they received and how the programme increased their enjoyment in education. Parents and whānau noticed a positive impact on their children from participating in the programme.

Make sure there are back-up options, like Summer School

Catch-up programmes can be worthwhile in responding to disruption. Making additional places available in Summer School programmes to support NCEA students appears to be an effective back stop for those learners who have experienced disruptions. The programme is suited to students who need a small number of credits to reach their goals.

Summer School was successful in meeting the need for NCEA students. The majority (90 percent) of students who submitted work during Summer School achieved at least one NCEA credit. Most students were using Summer School to achieve University Entrance.

Summer School may have also supported student wellbeing by providing them with a backup plan should they fall short of their goals. Enrolment into Summer School increased when students may have been feeling uncertain about achieving their NCEA goals by the end of the academic year.

Make sure schools can support students in school as well as providing options for students to be supported outside school

Following the Covid-19 lockdowns, schools were encouraged to support their students to reengage. We heard that schools were able to support many students in school. Teachers already knew the students and were well placed to provide them with the support they needed. The additional funding provided by the government to schools helped schools to support their students in school. Schools used the additional funding to hire teacher aides and counselling staff to support students and teachers.

Whilst targeted programmes such as TK400 can be effective, we recommend they complement rather than replace in-school support.

Only deploy programmes that require schools to partner with external providers when the benefits to the school and its students are clear

In times of crisis, schools need easily understood programmes to link up with. When considering a programme like Dual Tuition it is equally important to be aware of the demands such a programme can place on the school, and the need to establish a relationship between the school and provider. This can take more time than is available during a crisis response.

We found that schools were confused about the purpose of the programme, who would benefit most from it, and how it would operate. School leaders needed time to develop a relationship with Te Kura staff, and to build an understanding of how the programme would work in their school. It is also possible that the additional support accessed by some schools through the Urgent Response Fund meant that they were able to provide the necessary boost required for their students, by supplementing their own enhanced programmes.

Next steps

The ongoing impact of Covid-19 means there continues to be a risk of disruption to NCEA students learning. ERO has undertaken this evaluation to help us learn from the experiences of 2020, and to inform future responses to these kinds of disruptions. This report has been provided to The Ministry of Education and to Te Kura to help guide their work.

ERO is grateful for the time and input of all those who contributed to this evaluation

Appendix 1: Methods

Data collection

A mixed methods approach using qualitative and quantitative data was used in the evaluation.

Informed consent process

Permission from focus group participants was requested to record the Zoom / Team View audio-visual sessions.

No interviews or written survey data was collected from students under 14 years of age. Students and whānau / family participation in the data collection was voluntary. All participants were provided with an information sheet about the study.

Analysis and quality assurance

Two project team members undertook independent thematic analysis of the qualitative data using an agreed coding framework. The team members then compared analysis to check for consistency and refine the coding framework. A third person then undertook an independent check of the analysis for reliability, validity, and consistency of the coding and associated analysis.

8 data gathering methods were used to obtain information

- Interview questionnaire

- Student wellbeing survey

- In-depth interviews

- Focus groups

- Document analysis

- Analysis of administrative data

- Sense-checking workshops

- Literature rapid scan

1. Interview questionnaire

ERO designed a set of questions and prompts to collect the voices of students participating in the three programmes, and the views of their parents and whānau, and Te Kura staff responsible for those students. Using the ERO data collection protocol, the Te Kura project leads collected short written responses to questions about the impact of the interventions on students, parents and whānau.

Summer school students and teaching support staff were provided the questions via SurveyMonkey.

Student/ākonga interview questionnaire:

- 15 student responses from Te Kura 400 and Dual Tuition students collected in December 2020

- 8 student responses from Summer school collected in February 2021

Prompt for the interviewer: ERO and Te Kura are interested in your help collecting insights from students about their experiences of learning during the Auckland Region Covid 19 lockdown. The purpose of these questions is to help generate insights about the effect of Covid 19 on the student’s learning, and the role the opportunity to participate in the expanded Te Kura had on the students learning and engagement. The data will be used to create either vignette/case study and/or identify themes in experience. The data will be placed in the context of other information that will be collected.)

For Students / Ākonga – Introduction: We are interested in learning about your experience of the Auckland Covid 19 lockdown and what effects it has had on you and your family/whanau/fono particularly in relation to your schooling.

Interview with ākonga

Date:

Ākonga name:

Kaiāwhina/kaimanaaki name:

Interviews can be recorded/responses handwritten/responses typed.

- Tell me a bit about how Covid-19 has affected you, and your family/ whānau/ fono?

- How did you join the Te Kura programme? (Prompt - confirm programme Big Picture Dual-tuition, Summer School? Prompt - What was the educational pathway in/ who originated the way in/ how well did the pathway work?)

- What has taking part in the Te Kura programme meant for you? (Prompt - let the ākonga / family member self-define – Could encourage a response for example by asking trigger words such as: happy, sad, difficult, easy, helpful, exciting, encouraging, felt supported, re-engaged with learning, achieved the NCEA / Learning Credits I needed, transitioned to a Job, transitioned to a Benefit etc)

- If you didn't have the chance to be part of the Te Kura programme, what do you think might have happened with your learning?

- Is there anything else you would like to add?

Family/whānau/caregiver interview questionnaire:

- 9 family/whānau/caregiver responses from Te Kura 400 and Dual Tuition (combined) provided in December 2020

- Logistical constraints meant that family/whānau/caregivers of Summer school students did not provide responses