Summary

This report provides findings from ERO's evaluation of how well schools were promoting and supporting student wellbeing through sexuality education.

It includes high-level findings, examples of good practice and recommendations for schools and policy audiences. It is accompanied by a series of short publications for whānau, students, and trustees.

Brochures aimed at students, whānau and Boards of Trustees are also available.

- Sexuality education in primary schools - information for boards of trustees [123.34 KB]

- Sexuality education in primary schools - information for whānau [83.4 KB]

- Sexuality education in secondary schools - information for boards of trustees [87.28 KB]

- Sexuality education in secondary schools - information for senior students [83.51 KB]

- Sexuality education in secondary schools - information for whānau [85.37 KB]

Whole article:

Promoting wellbeing through sexuality educationForeword

Sexuality education is part of the Health and Physical Education and Hauora wāhanga ako learning area within The New Zealand Curriculum (2007). The curriculum promotes a holistic approach to sexuality education including physical, social, cultural, emotional and spiritual considerations, and must be included in teaching programmes in both primary and secondary schools. At the heart of the curriculum is young people learning about themselves, developing skills and confidence to interact with others in a positive and respectful way, and knowing how to seek help and support when it is needed.

High quality sexuality education is critical to children and young people’s development and wellbeing.

The changing social context has profound implications for effective sexuality education.

The ubiquity of smartphones, online and digital content, and the growing influence of social media means that a wide range of sexualised content, including exploitative and negative stereotypes, is readily accessible. Quality sexuality education must be more than teaching about biology. It must give our children and young people the skills to discriminate this barrage of media messages, and to keep themselves safe.

The cultural conversation is moving fast. There is an increasing awareness of issues around sexual harassment, the fundamental importance of positive consent, and much greater visibility and celebration of diversity. Affirming and inclusive learning environments combine effective teaching and learning with the conditions within a school to also promote wellbeing. Schools need to challenge discrimination, and to actively support all students to participate and succeed while positively expressing their identities within inclusive and welcoming school environments

We know sexuality education can be a challenging area for school trustees, leaders and teachers, and that the issue can be divisive in school communities. A whole of school approach is about the ethos, structures and processes, organisational models and partnerships across the school community that supports both the sexuality education programme and a positive school culture. Strong leadership is needed at the school, community and system level. The pace of social change also requires our schools to continue to grow, evaluate and adapt their teaching and learning programmes.

ERO’s national evaluation paints a picture of where our schools are at today in responding to the current context, and showcases the practices of a group of schools effectively meeting the challenges of our current context. To those who have given their time and support to make this important evaluation a reality – thank you.

Nicholas Pole

Chief Review Officer Education Review Office

September 2018

Overview

This report provides findings from ERO’s evaluation of how well schools were promoting and supporting student wellbeing through sexuality education. It includes high-level findings, examples of good practice and recommendations for schools and policy audiences. It is accompanied by a series of short publications for whānau, students, and trustees.

Comprehensive sexuality education can equip students with the skills, attitudes and understanding necessary to support positive environments for all students, including those with diverse genders or sexuality. It can contribute to the overall health, wellbeing and resilience of young people (Ministry of Education, 2015), as well as improving attitudes to gender and social norms, and building students’ self-efficacy. Wellbeing is important for students’ success, for example, a student’s sense of achievement and success is enhanced by a sense of feeling safe and secure at school. It is important to develop young people’s resilience from an early age: to increase their educational achievement and quality of life, and prevent youth suicide (Gluckman, 2017).

International studies have highlighted the benefits of comprehensive sexuality education for sexual health, including reducing risky behaviours and improving the rates of contraceptive use. Comprehensive sexuality education presents abstinence as a legitimate and safe choice, and has been shown to lead to delayed sexual debut for young people. Programmes that focus on abstinence as the only moral choice, however, can sometimes delay sexual debut, but also create risk of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections by withholding information about contraception, and fail to address issues relevant to sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students.1

The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) (NZC) includes sexuality education as one of seven key learning areas in health and physical education. Health and physical education in the NZC is based on four concepts: hauora, attitudes and values, the socio-ecological perspective, and health promotion. The focus is on the wellbeing of the students themselves, other people, and society through learning in health-related and movement contexts (Ministry of Education, 2007. p 22).

In 2015, the Ministry of Education published Sexuality Education: a guide for principals, boards of trustees and teachers (Ministry of Education, 2015). This document is a revised version of an earlier guide (2002). The revision considers recommendations in the Health Committee’s (2013) report on improving child health outcomes, as well as recent research and changing understanding and social climate towards sexuality and sexuality education. The guide lays out examples of what kinds of content students should learn at each level – from Year 1 through to Year 13 (see Appendix 3).

For this evaluation, we visited 116 schools that had their regular ERO external evaluation between May and August 2017. In each school we asked: How well does the school use sexuality education to support and promote wellbeing for their students? Additionally, a specialist team of evaluators visited 10 schools identified by external stakeholders as having good practice in sexuality education and inclusion.

This evaluation took a broad approach, investigating the sexuality education curriculum within the whole school context. ERO was also particularly interested in the extent to which schools were providing an inclusive environment for sex-, gender- and sexuality- diverse students to support their wellbeing. A group of external experts supported ERO to develop indicators of quality sexuality education (Appendix 1) for each domain of ERO’s School Evaluation Indicators:

- stewardship

- leadership for equity and excellence

- educationally powerful connections and relationships

- responsive curriculum, effective teaching and opportunity to learn

- professional capability and collective capacity

- evaluation, inquiry and knowledge building for improvement and innovation.

ERO last reported on schools’ provision of sexuality education in 2007. The evaluation found many schools were not effectively meeting the needs of students. In particular, schools were not meeting the needs of Māori or Pacific students, international students, students with strong cultural or religious beliefs, students with additional learning needs and students who were sex-, gender- or sexuality-diverse.

In the 2017 evaluation, ERO found that, overall, curriculum coverage remains inconsistent. Some schools are not meeting minimum standards of compliance with current requirements. Most schools are meeting minimum standards, but many have significant gaps in curriculum coverage. Although biological aspects of sexuality and puberty are well covered, more in-depth coverage is needed for aspects like consent, digital technologies and relationships. Sexual violence and pornography were covered in fewer than half of the secondary schools ERO visited.

Furthermore, the groups identified as being disadvantaged in the 2007 report remain less well catered for, despite being at higher risk of negative wellbeing outcomes.

Findings

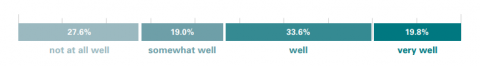

How well is sexuality education taught? (percentage of schools visited)

Definitions of ratings for overall judgment

Not at all well: Not compliant across at least four domains

Somewhat well: Compliant across at least four domains

Well: Compliant across all domains

Very well: Compliant across all domains, and demonstrates some additional evidence of good practice across at least four domains

Characteristics of effective implementation

When sexuality education was well taught, school leaders recognised the importance of this aspect of the curriculum for student wellbeing. Leaders made sure students had opportunities to learn from teachers or external providers with relevant expertise and experience. Trustees and leaders worked together to make sure they consulted with the community on how the school planned to give effect to sexuality education as part of the health curriculum, and that students and parents/whanau were able to have meaningful input into the content and delivery of the sexuality education programme.

Sexuality education was well planned, age- appropriate and provided opportunities for students to work towards developing empathy and, at senior levels, to engage in critical thinking about sexuality.

Teachers who had responsibility for sexuality education stayed up to date with good practice in sexuality education and broader societal issues relating to sexuality. They shared their expertise with colleagues, to create a whole-school environment of awareness and inclusion. Teachers and others in schools modelled the use of inclusive language and pushed back against homophobic or transphobic language used by students.

Common barriers and challenges

The most common barrier to effective implementation was a lack of specific planning for a comprehensive approach to sexuality education. Contributing factors included:

- absent, or inadequate, community consultation

- lack of assessment and evaluation in sexuality education

- lack of teacher comfort and confidence

- low prioritisation of sexuality education among other competing priorities

- school policies not widely understood and implemented.

Only a few schools conducted regular evaluation of their sexuality education provision, or undertook robust analysis of the perceptions and needs of their students in this learning area.

In a few schools, real or perceived community opposition to sexuality education for religious or cultural reasons has meant schools provided inadequate sexuality education programmes that did not address important aspects of the curriculum.

These barriers and challenges led to variability in practice across schools. While some schools offered comprehensive sexuality education that met the needs of their students, others did not adequately provide for students’ learning in sexuality education. This variability, and lack of reference to students’ needs was also of concern to students, as demonstrated by the student research recounted on the following page.

This narrative is from one school where students contacted ERO on their own initiative after learning of the sexuality education evaluation and wanting their school’s good practice to be included.

Student research into the quality of sexuality education

This story is an example of inquiry-based, socially conscious learning around sexuality education issues from outside the health curriculum.

High quality, comprehensive sexuality education can lead to the realisation of the NZC’s vision, values and key competencies, as demonstrated by the social action taken by a group of Year 12 students who approached ERO.

These students wanted to share the findings of a survey they conducted around local students’ experiences of sexuality education. The girls were concerned about inconsistency in the sexuality education received by them and their peers, and so they conducted a survey for an assignment for their sociology class, where they were required to take a social action.

The survey asked questions such as:

Question: Do you think the sex education course was specialised for your school (e.g. religion, culture)? What area/s of [sexuality education] do you feel you know the most about?

Answer: We learned about the physical parts of sex, like always have a condom, but we were never taught about the emotional or social aspects, the sexual interactions of people of the same gender.

Question: In most schools, sex ed is only taught up to Year 10. Do you think that this is taught up to a high enough year level? Why/why not?

Answer: I think it should be talked about till the end of our school years since like Year 11, 12 and 13 are the years when people become the legal age and that’s when they will be experimenting with their bodies and their sexuality. I feel like schools avoid the topic because they don’t want to encourage sexual activity in young people, but they will do it anyways but they will just have to teach themselves.

It’s important to know from ages like in Year 10 and 9, just in case a few Year 9s and 10s are actually having sex, nitwits! Sexual education is important in Years 11 and 12 at least, because it’s not enough to tell someone something and hope they remember it for the rest of their life. Why do you think we do REVISION for exams?

Students from nine different secondary schools completed the survey, and most were in Year 12. Only 10 percent thought their sexuality education programme was tailored to their context and needs. Most remembered learning about the physical side of sex, but many felt other aspects of sexuality education could be strengthened. They provided suggestions about how sexuality education programmes could be improved to better meet students’ needs.

Survey respondents wanted their school to:

Teach us more about the emotional impacts of a physical and emotional relationship with another person and to be open minded.

- Cater to everyone’s needs whether it be religious or cultural beliefs.

- Cover the emotional parts of it as well as the physical.

- [Use] more realistic scenarios, all the videos and much of the coursework was way outdated.

- Take safe sex within LGBT communities seriously and enforce nondiscriminatory attitudes within the classroom as well as theoretically, e.g. not allowing slurs.

- While the basics were covered, it was the bare minimum. The way it was taught was made to scare students instead of inform them. We need to be informed about the ‘harder’ subjects.

- Do it in older years, consider people’s religious and cultural beliefs, and make sure it covers everything in the context of real life situations.

The girls were passionate advocates for improving the quality and consistency of sexuality education. Their survey findings showed that students did not feel their needs were met by the sexuality education they received. The girls felt empowered to advocate for themselves and others, and were critical, informed, active and responsible citizens.

Domains of practice

The following sections report in more detail on the performance of schools in each of the School Evaluation Indicator domains as they relate to sexuality education.

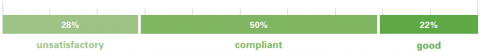

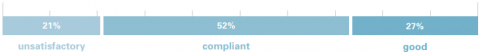

Each section begins with a graph showing the percentage of schools in the sample whose performance was unsatisfactory, compliant or good. It is important to note that achieving compliance means that the school met defined minimum standards of quality for that domain (see Appendix 1). To be effective and to implement the intent of the 2015 sexuality education guidelines in these areas, these schools still required substantial improvements.

Stewardship

As part of their stewardship role, boards of trustees (boards) have the responsibility to make sure they scrutinise the delivery of sexuality education in the curriculum. Boards are also responsible for making sure school policies are inclusive and support student safety and wellbeing. Uniforms and bathrooms were the most commonly cited issues around inclusion of sex-, gender- and sexuality- diverse students.

In the schools with good stewardship, school leaders and teachers reported to trustees regularly on programme delivery. In a few cases, trustees also attended parent information evenings, and/ or requested and received reports from pastoral staff like guidance counsellors and nurses on common sexuality issues, and used this to review programmes and resourcing.

These boards also demonstrated a positive view of sexuality diversity and developed policies that promoted diversity, both for students and also for staff who identified as sex-, gender- or sexuality- diverse. One board chair told ERO they took their responsibilities to their students very seriously, going on to say: it’s hard enough going through school as a teenager. If there’s anything a school can do to support with additional stressors, they should. It doesn’t matter how many it’s an issue for, if it’s an issue, it’s an issue.

In a few secondary schools, trustees were active in supporting student LGBTQI groups. Some of these schools had adopted a gender-neutral uniform policy or dress code. This could be as simple as providing the same range of uniform options as before, but dropping the designation of certain items as being for boys or girls.

In the schools with compliant stewardship performance leaders reported information to boards at a general level about what the sexuality education programme covered, rather than more detailed information on student needs, learning and progress.

The boards in most of these schools had good child protection policies in place for reporting on bullying or harassment, but did not necessarily have policies that promoted inclusion for diverse students. Support for sex-, gender-, and sexuality-diverse students was often implicit and reactive rather than explicit and proactive. Some schools provided gender-neutral bathrooms for students, but in many, leaders and trustees saw this as being prohibitively expensive or not possible with current property arrangements.

Some boards reported they did not have any such students, or these students were covered by more general diversity policies. However, research suggests strongly that sex-, gender- and sexuality- diverse students are present in the vast majority of schools. Where leaders or teachers felt this was not an issue for them, it could be that these students’ voices were not being sought, and their needs were not being recognised. Furthermore, student voice gathered through ERO’s good practice visits highlight that without explicit support, these students perceive the school environment as indifferent or hostile. To be truly inclusive, schools should consider how their policies and practice can support these students before they are prompted by a specific enrolment.

In the schools with unsatisfactory stewardship performance, sexuality education was a low priority for boards. Some of these schools had no planned sexuality education programme. In some other schools, there was a programme in place, but the board did not scrutinise the delivery. In many of these schools, the board was unaware of their responsibilities to make sure they consulted with the community about the implementation of the health curriculum.

Leadership

In schools with good leadership for sexuality education, leaders took a crucial role in both ensuring the comprehensive coverage of sexuality education as part of their school’s curriculum, and leading the development of an inclusive school culture in which sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students feel welcomed and do not face barriers to their learning and wellbeing.

Leaders in these schools committed resourcing to support delivery of sexuality education. This could include:

- developing clear curriculum guidelines and expectations about topics to be covered

- allocating sufficient classroom time for teaching

- holding meetings to make sure that all staff understood the programme

- providing access to high quality teaching resources.

When external providers were used to deliver parts of the programme, leaders were deliberate and discerning in their selection of providers and/ or programmes, using internal evaluation to assess whether the programmes were meeting the needs of students. In secondary schools, a few leaders made sure there were opportunities for students who were not taking health at the senior level to be engaged in ongoing learning, through seminars or workshops from external providers, or through exploring sexuality issues in other curriculum areas.

Another aspect of good leadership, particularly at secondary school level, was support for student leadership groups. ERO found secondary students were empowered to create groups for peer support and peer education. Peer support groups (e.g. queer-straight alliance groups) helped students to feel included and safe at school, while other groups (e.g. Thursdays in Black, or feminist groups) played a role in raising awareness of sexuality-related issues among staff and students, raising money for local charities or non-governmental organisations, or working with health teachers to provide peer education in a classroom context.

In schools with compliant leadership, sexuality education was planned for, but was not a high priority. ERO’s previous (2007) report suggested that around 12-15 hours of classroom time per year was necessary to provide comprehensive sexuality education at the secondary level. Only a few schools met this benchmark. Some leaders cited a crowded curriculum as a barrier to providing this level of time.

In primary schools, ERO found some reliance on school culture and environment to teach friendship, communication and relationship skills, rather than planning for explicit teaching with a view to building towards the requirements of the higher levels of the curriculum as set out in the Sexuality Education Guidelines.

In almost all schools, leaders spoke of a commitment to including sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students in their schools, which was reflected in school values and policies. However in many schools, the level of inclusion varied, with some teachers using inclusive language and demonstrating sensitivity to the wellbeing needs of diverse students, while for others this was not evident.

In schools with unsatisfactory leadership for sexuality education, this aspect of the curriculum was not valued. Consequently, there was little coherent and sequential planning of the sexuality education programme, and in some of these schools the term ‘sexuality education’ was not used. There were few clear expectations for curriculum coverage. Some leaders in these schools brought in external providers, but without a clear rationale for why they were selected and without evaluating their effectiveness.

Connections

Schools must consult with their community about what is taught in health programmes, including sexuality education (Section 60B Education Act 1989). Parents may ask the principal to ensure their child is excluded from the sexuality education parts of the health curriculum (Section 25AA Education Act 1989).

In schools with good connections and relationships for sexuality education, trustees and leaders made sure their community were kept well informed about the sexuality education programme and had opportunities to provide input to the programme. In these schools, there were a variety of avenues for consultation. Leaders and trustees were well aware of the cultural diversity of their schools and made sure consultation was conducted in appropriate ways. They built on their well-developed pre-existing connections with communities. In many of these schools there were regularly scheduled whanau hui, or similar meetings, and the school used these opportunities to engage in face-to-face consultation on the health curriculum. In some schools, teachers who had links with specific communities conducted home visits to make sure parents/whānau understood what was going to be taught in sexuality education. Another school engaged a community liaison worker to facilitate communication with parents.

In most of these schools, parent/whānau and student perspectives gathered through the consultation process were taken into account when developing the sexuality education programme.

In this way, these schools were able to make sure the programme addressed the needs of their student population and reflected the values of their communities.

These schools also had strong connections with a variety of external groups like iwi, health services, Police and a few of the schools had engaged with non-governmental organisations with a specific focus on sexual health, or inclusion of sex, gender and sexuality-diverse students.

In schools that were compliant in this area, consultation tended to be treated as a tick-box exercise, rather than an opportunity for genuine engagement and discussion. Most of these schools provided parents and whānau with a survey, for which response rates were often low. A few schools ran community meetings specifically for health curriculum consultation, or ‘piggy-backing’ on other events that parents and whānau attended, but did not have the strength of educationally powerful connections that was evident in the more highly performing schools.

In some instances, actual or perceived conservatism on the part of the community led schools to provide less than comprehensive sexuality education.

Schools with a strong religious focus were more likely to be explicit about how they considered the interplay of community values and the values of The New Zealand Curriculum, with the special character values generally taking precedence.

These schools were generally good at making sure their students were connected to local community health resources as needed, most commonly a community health nurse.

Some schools had unsatisfactory connections. In most cases, this was because the boards did not meet their legal obligation to consult every two years, either because they were unaware of the requirement to do so, or because of the low priority afforded to health in the school’s curriculum. In a few cases, a lack of specific planning for sexuality education meant there was very little curriculum content on which to consult with parents/whānau. A few of the schools did consult, but at such a low level (e.g. informing only, or distributing a very short survey) that they were unable to build an informed picture of community needs and preferences.

Curriculum

Sexuality education was generally located as part of the health curriculum, or as part of religious education in Catholic state-integrated schools.

In some of the good practice visits in secondary schools, ERO found there were opportunities for sexuality education topics to be covered in other subjects, for instance, looking at gender roles and stereotypes in social studies, or changing attitudes to sexual identity in history or classical studies. Many schools also brought in external providers to conduct focused sessions on different aspects of sexuality.

In schools with a good curriculum, the sexuality education programme was comprehensive and age-appropriate, covering the areas of:

- anatomy, physiology and pubertal change

- friendship skills

- relationships

- conception and contraception

- gender stereotypes

- communication skills

- consent and coercion

- gender and sexuality diversity

- sexually transmitted infections*

- sexting*

- pornography*

- alcohol and drugs as they relate to sex*

- sexual violence*

(* in secondary schools)

Teachers in these schools were confident and knowledgeable, and were skilled at creating a classroom environment of high trust and safety. Students found it comfortable to talk about sexuality education topics without judgement. Teachers modelled inclusive language and behaviour and dealt well with homophobic or transphobic language used by students when they were made aware of it.

Teachers were also sensitive and responsive to the range of maturity levels in their classrooms.

The sexuality education programme in these schools provided many opportunities for students to explore different values and beliefs. Students were able to undertake a variety of activities, e.g. written tasks, research, surveys, role play.

The sexuality education programme in these schools was also responsive to students’ preferences and input. Teachers sought student voice about what should be covered and how, and built this into their planning. In a few secondary schools, students taking senior health were able to have input into the programme by way of their self-directed research and health promotion projects.

In schools that were compliant, curriculum coverage had some gaps. The most commonly covered topics in school curricula were more general communication skills, self-esteem, friendship skills and relationships. This was true for both primary and secondary schools. However, school leaders and teachers provided little detail about how these topics were specifically taught – many leaders stated these topics were ‘woven through’ all teaching and learning, or were evident in school vision and values. The Ministry of Education is currently finalising sexuality education resources to support schools to strengthen their teaching of friendship, belonging and puberty for levels one to four of The New Zealand Curriculum.

Of the more specific sexuality-related topics, the most commonly covered across primary and secondary schools was anatomy, physiology and pubertal change. Gender stereotypes and gender and sexuality diversity were also more commonly covered relative to other topics, though much more so in secondary schools than in primary schools, with only around one third of primary schools teaching about gender and sexuality diversity, and around half teaching about gender stereotypes.

This rose to around 70 percent for diversity, and nearly 90 percent for stereotypes in secondary schools. The two least often covered topics in secondary school were sexual violence and pornography; both were covered in less than half of the secondary schools ERO visited.

In schools with an unsatisfactory curriculum there were large gaps in coverage. Many of these schools had no specific and planned sexuality education programme at all, while others relied on external providers without integrating provision into their regular curriculum.

Dealing with homophobic language

In one school, the pastoral care team told ERO: youth today are more accepting than we were… there’s more awareness, more education, but the hardest thing to tackle was the covert, pervasive language and behaviours. They recognised that students are a product of society and the wider discourses of society. Staff responded seriously when they knew about bullying, but it was often subtle, online, and students did not always tell teachers when bullied.

A senior health class looked at the use of homophobic language, such as ‘that’s gay’ for a health promotion assessment.

They thought students using that language did not know or understand that it could be offensive, and a change was needed in the whole school. Senior students told ERO that respecting diversity should be a conversation from Year 9, built into conversations about how we do things here. They thought it was important to be explicit.

Students noticed there had been greater awareness of diversity and the way people speak in the school in recent years. They appreciated teachers calling out students for using homophobic language, and saw that students also monitored each other’s language. Senior students were confident that overall culture change would happen.

They said we’re really lucky to have such a supportive school. We have the means to change.

External providers

In this evaluation, ERO did not take a strong view on whether different aspects of sexuality education were best taught by teachers employed at the school or external providers. Instead we evaluated the extent to which school leaders (or whoever had oversight of external provision) were deliberate and discerning in how they selected external providers appropriate for the needs of their student population.

Most schools need to do more internal evaluation of how external providers support their sexuality education programme. ERO found only a few schools where the selection of external providers and programmes was informed by regular evaluation.

School leaders and trustees therefore did not usually have robust evidence of how external providers contributed to valued student outcomes.

In primary schools, the most common external providers were the Life Education Trust and the New Zealand Police’s Keeping Ourselves Safe (KOS) programme. These are more general programmes that cover personal safety and pubertal change, along with other health aspects such as food and nutrition and physical activity, and drug education. In many schools, this external provision comprised the majority or totality of their sexuality education curriculum. Full primary and intermediate schools were more likely to be using Family Planning’s Sexuality Road programme, for their Year 7 and 8 students.

Secondary schools were more likely to have trained specialist health teachers, and external providers were used more on a supplementary basis. Specific programmes included the Accident Compensation Corporation’s (ACC) Mates and Dates programme, the New Zealand Police’s Loves-Me-Not programme, and various shorter seminars given by a variety of providers.

Evaluating the quality of this external provision was beyond the scope of ERO’s evaluation. However, it is worth noting ERO found a lack of internal evaluation by school leaders of how well these programmes met the needs of their students.

Some students we spoke with suggested they would prefer if sexuality education was provided by teacher they already had a relationship with. Other students said they felt more comfortable speaking with external educators who they would not have to see on a day-to-day basis. It is likely this will vary for students individually and for different aspects of sexuality education. To better meet the needs of their students, schools need clarity on student needs and preferences.

Capability

For sexuality education to be effective, it is critical that it be taught by well-trained, confident and capable teachers or other educators. In secondary schools, it was more common for leaders to employ health and physical education teachers with expertise in sexuality education, but ERO found a few schools where leaders had explicitly looked for this expertise when recruiting. Very few primary schools employed teachers with specific expertise in sexuality education. While some school leaders told ERO they appreciated the publication of the 2015 Sexuality Education guidelines, ERO found wide variance in their level of uptake and implementation. A few school leaders were not aware of the guidelines.

In schools with good capability, there were clear policy guidelines to support staff to have a consistent and informed approach to sexuality education and inclusion. Teachers and other staff supported one another in their areas of strength, and accessed professional learning and development from a variety of internal and external sources, including:

- curriculum leaders

- school guidance counsellors

- chaplains

- social workers

- Sexuality Education guidelines

- Police

- public health nurses

- externally run workshops or conferences.

Many of these schools also made sure any external provision or programming (e.g. Family Planning) included a capability-building focus for staff to improve sustainability and made sure students were receiving consistent, well-informed messages around sexuality education. Many schools had also undertaken specific professional development focused on inclusion of sex-, gender-, and sexuality- diverse students, and made sure this included all staff, not just teachers. In a few of these schools, professional learning and development was linked to robust internal evaluation to identify staff learning needs.

In one school, when appointing new staff, leaders and the board considered how well candidates fit the inclusive culture of the school. It was important all staff valued diversity and inclusivity. The school then supported all new staff with a strong induction process. The guidance counsellors met with all staff new to the school, to induct them into the culture of the school. The counsellors also worked with staff to help them be aware of their language use, their students’ needs, and the importance of not making assumptions about their students.

In schools that were compliant, the quality and quantity of professional learning and development was variable. It was more likely to be informal and internal. In some of these schools there was also a variable level of confidence and capability among staff. One student told ERO reviewers their sexuality education was “dependent on which teacher they had, as some were more comfortable to deliver the whole programme, and others just stayed on physical puberty, reproduction and friendship and stayed away from the stuff that made them uncomfortable.”

In these schools, policies for reporting suspected abuse or handling disclosures were well understood and followed, but they were less likely than the schools with good capability to have undertaken specific capability-building for inclusion of sex-, gender-, and sexuality-diverse students. In a few cases ERO’s evaluation had prompted leaders to think about how they might improve in this area.

In many of the schools with unsatisfactory capability, there had been no recent professional learning and development in sexuality education. Most of these schools tended to be ones where the sexuality education programme was insufficient or effectively absent. In some cases, teachers appeared not to have an awareness or understanding of the importance of sexuality education in general. In one school staff told ERO reviewers “there were no issues at the school” and they “would deal with it if it was identified in student surveys but students don’t bring it up.” In the same school, students told ERO reviewers that a fellow student who identified as fa’afafine was the subject of gossip and homophobic comments.

Of most concern, in a few of the schools, teachers were not aware of the policies and procedures around reporting abuse or handling disclosures.

Evaluation

Internal evaluation is crucial if teachers and leaders are to understand the needs of their student community, and the extent to which their delivered curriculum is meeting those needs. Across schools, evaluation was the weakest of the domains that ERO investigated for this evaluation.

In the few schools with good evaluation students had opportunities to provide substantive input into, and feedback on, the sexuality education curriculum, often through student leadership groups. In these schools there was also clear evidence of assessment of students’ knowledge in sexuality education that was reported to the board. In secondary schools, where students took senior health, they were more likely to be assessed in learning about sexuality education. In primary schools, relevant assessment was focused more broadly on students’ achievement of key competencies like relating to others and managing self.

In schools that were compliant, students had more limited opportunities to provide input, such as through a postbox for asking questions during sexuality education lessons. Formal assessment of student progress in sexuality education was variable. Very few schools reported to parents on sexuality education achievement. Consequently, evaluation of sexuality education provision, when it did occur, focused mostly on what had been delivered, rather than learning outcomes for students.

In schools with unsatisfactory evaluation, students did not have any say in what was covered in the programme, either because the school relied on external providers, curriculum decisions were made without reference to student voice, or the school was not providing sexuality education at all. Any evaluation that did occur was informal and not well connected with programme development. Some leaders told ERO that their schools were inclusive and welcoming environments, but were not able to show evidence of this.

Some New Zealand research suggests students perceive the sexuality education they receive in school to be insufficiently comprehensive (e.g. Allen, 2011). Teachers, leaders and parents/ whānau may believe enough is being covered, but if schools are not regularly collecting information about what students want to learn and evaluating their programmes, there is a risk that they are not meeting their students’ needs. This was reflected in some student comments made to ERO evaluators.

For example, in one secondary school, the curriculum leader stated they thought almost all the aspects of sexuality education were covered, but a group of students told ERO they did not feel all of these aspects were covered or that they were skimmed over. They felt that generally the sexuality education topics focused on puberty, relationships and homosexuality. The students felt the school could do better by finding out what the students wanted to know more about and create a programme that reflected that. Students also thought it should be compulsory rather than optional at Years 11 and 12. The school guidance counsellor felt that what the students were saying to her in sessions was similar to what they had said to ERO and more needed to be done to meet the students’ needs in terms of sexuality education.

In another secondary school, senior students ERO spoke with felt their own awareness about issues relating to sexual orientation had increased but identified they would like to spend more time on this. They believed young people were exposed to sexuality through media and from peers without enough relevant education to help them respond to this in a healthy way. A senior student said they wanted the school to be more proactive with sexuality education and to educate students “early before social media does.”

These comments, and other similar ones, highlight the need for schools to conduct robust internal evaluation about the extent to which their sexuality education curriculum is meeting the needs of their students.

Discussion

Since ERO last evaluated sexuality education in 2007, the social and technological context around sexuality and sexuality education has shifted quickly and profoundly. Overall, the quality of schools’ sexuality education programmes have not kept pace with this shift.

The ubiquity of internet-connected smartphones and the growing influence of social media create an environment in which young people are exposed to a broader range of sexuality-related content at an earlier age than previously. Without the knowledge and skills to navigate this context, young people are at risk of developing unhealthy attitudes toward sexuality, increasing risks to mental and physical wellbeing for themselves and others. There have been a number of high-profile issues related to sexuality, including the Roast Busters scandal, and the protests sparked by misogynistic language used by some students on social media, as well as the broader #MeToo movement with its focus on exposing the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault. These show both the risks young people face when a healthy understanding of consent is not widely held, and the increasing demand from school students for effective sexuality education to address these issues.

International research2 suggests that pornography is becoming an increasingly accepted and prevalent aspect of young people’s sexuality experiences.

However, research also identifies a range of negative outcomes associated with viewing pornography, including mental and sexual health issues.

Pornography rarely depicts meaningful consent, and often includes coercion and/or violence, particularly towards girls and women, as a normal part of sexual encounters.

Upcoming draft survey findings from the Light Project3 suggest that these patterns are also visible in the New Zealand context, and highlight that many young people in New Zealand are learning about sex through pornography. This creates unhealthy views about sex and relationships, and is leading young people to engage in physically and emotionally risky behaviours. It is therefore of some concern that ERO found pornography was one of the least well covered aspects of sexuality education. ERO therefore recommends further investigation into the impact of pornography on young people.

In New Zealand, performance against several high-level indicators of sexual health for young people has improved. The rate of teenage pregnancy declined between 2001 and 2013 (Statistics New Zealand, 2013), and young women are having fewer abortions (Statistics New Zealand, 2017). The rate of sexually transmitted infections also decreased for young people between 2010 and 2014 (The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd., 2015). While this is encouraging, sexuality education is intended to contribute to a broader range of wellbeing outcomes than these negative proxy indicators can capture.

Furthermore, these improvements are not yet equitable. Māori are more likely to become teen parents than non-Māori (Marie & Fergusson, 2011). Māori women aged between 15 and 19 have a higher rate of abortions than any other ethnicity of the same age group (National Institute of Demographic and Economic Analysis, 2015). Gonorrhoea and chlamydia are 2-3 times more common in Māori women aged 15-19 (The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd., 2015) and young people from neighbourhoods with high levels of deprivation are less likely to regularly use contraception (Clark et al., 2013).

To meet the needs of young people in our current context, sexuality education needs to be more comprehensive and the variability across schools needs to be reduced. This evaluation found some schools were failing to meet minimum standards of effectiveness, and many more were only just meeting these standards. Given the complexity of the issues involved, and the impact sexuality issues have on young people’s wellbeing, this performance is not good enough. The publication of the Sexuality Education guidelines is a good starting point, but ERO recommends the Ministries of Education and Health provide more support for implementation of the guidelines and targeted professional learning and development to increase teacher confidence and capability to deliver sexuality education. Additionally, since ERO’s data collection for this evaluation, the Ministry of Education has published a guide to supporting LGBTIQA+ students. This is timely, and ERO suggests that the Ministry of Education review schools’ awareness of this document to make sure it is reaching the intended audience.

In primary schools, the sexuality education programme is generally delivered in the form of Life Education Trust visits and the New Zealand Police’s Keeping Ourselves Safe programme. In most secondary schools, sexuality education is taught as part of compulsory health education in Years 9 and 10, and then optional after that for students who take health as an NCEA subject. Some schools augment this with opportunities for students to learn about aspects of sexuality education from externally provided programmes (especially ACC’s Mates and Dates) or peer educators. Evaluating these external providers was beyond the scope of ERO’s evaluation, but ERO found that only a few schools were conducting internal evaluation of the effectiveness of the programmes in meeting their students’ needs.

Recommendations

ERO recommends the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health work together with expert partners to:

- provide greater support for implementation of the 2015 Sexuality Education guidelines, including:

- working with schools to understand teachers’ professional learning and development needs and explore opportunities to provide training in sexuality education

- developing a co-ordinated cross-agency expectation around whole-school approaches to sexual harassment, including online

- promote sustainability by prioritising funding and support for external providers of sexuality education that include a focus on building teachers’ and other school staff capability

- support the development of sexuality education resources and programmes that address the needs of diverse populations currently under- served by existing provision, especially:

- Māori students and whānau

- Pacific students and communities

- students with additional learning needs

- sex-, gender-, and sexuality-diverse students

- over time, evaluate the use and usefulness of the recent guide to supporting LGBTIQA+ students

- further investigate the impact of pornography on young people in New Zealand

ERO recommends that schools:

- use this report, along with the Sexuality Education guidelines to review their sexuality education programme

- implement a comprehensive sexuality education programme, making sure sufficient time is provided for delivery and that students at all levels have opportunities to engage with sexuality education

- develop robust whole-school expectations around how to deal with sexual harassment and bullying, including modelling respectful language

- proactively consider how to promote an inclusive and welcoming environment for sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students, including reviewing uniform and bathroom options

- make sure they use the mandated consultation process4 effectively to gather meaningful student and whānau voice to inform the development of their sexuality education programme

- make sure teachers have sufficient professional capability to effectively teach sexuality education, and access professional learning and development as needed

- consider how their sexuality education programme is relevant and responsive for students who have generally been underserved, including:

- Māori students

- Pacific students

- migrant students

- students with additional learning needs

- sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students

- evaluate the use of external programmes and resources in sexuality education, prioritising those programmes and resources that include an explicit focus on improving staff capability

- empower student-led support and advocacy groups.

Good practice narratives

ERO visited ten schools that had been identified by external stakeholders as having good practice in sexuality education, and/or doing a good job of including sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students.

In selecting these schools, we consulted with education, health and community youth groups.5ERO’s outcome indicators for students set out our vision for confident, connected, actively involved lifelong learners. At the end of each narrative, we have noted the student outcome indicators that were evident in these schools.

Common to these narratives is the recognition by leaders, trustees and teachers of the importance of comprehensive sexuality education in supporting student wellbeing. Crucially, leaders and teachers in these schools paid attention to the voices of their communities, and especially their students, around what they knew, and what they wanted to learn more about. The narratives in this report contain several examples of schools engaging in genuine consultation with their students and whānau.

Leaders, trustees and teachers in these schools recognised there were diverse views within their communities about sexuality education, but found most parents and whānau were supportive of comprehensive sexuality education once they were fully consulted and informed. Parents retain the right to withdraw their children from any or all aspects of sexuality education (Section 25AA Education Act 1989). They are entitled to make this decision for their own children, but this should not impede the development of a comprehensive programme for other students in the school.

Additionally, leaders in these schools had established an environment of collective responsibility for inclusion that meant sex-, gender- and sexuality- diverse students got consistent messages around belonging, and were more able to feel safe and accepted at school. These schools were proactive, rather than reactive, and did not simply rely on more general policies and practices around inclusion, but took the time and effort to think about how they could send the positive message for sex-, gender- and sexuality-diverse students that they were welcome and cared for.

ERO recommends that leaders and teachers read the narratives in conjunction with the Ministry of Education’s 2015 Sexuality Education guidelines. We have noted elements of the narratives that illustrate specific sections from the guidelines, to give leaders and teachers a sense of what implementation of the guidelines can look like in practice.

01. Culturally responsive sexuality education

This story highlights how one school is teaching culturally responsive sexuality education in a bilingual context.

This large co-educational secondary school has a unique co-governance model. There is a distinct Māori-medium rumaki onsite, with over 200 Māori students, which operates autonomously. The bilingual component of the college is well regarded for the success Māori students achieve as Māori.

The school draws from a creative local community that supports the student-centred bi-cultural kaupapa of the school. Health education, including sexuality education, for students attending the rumaki is delivered in a culturally responsive context by specifically selected Māori teachers.

The teacher with responsibility for sexuality education told ERO that one of the distinctive aspects of culturally-responsive sexuality education for Māori was the holistic approach, grounded in the notion of hauora. She worked closely with the head of health to adapt the school’s strong sexuality education programme to the rumaki context. The teacher told ERO:

The good thing within the rumaki is that, because hauora is such a kaupapa that is a part of everything Māori, that it doesn’t matter if it’s the science teacher or social studies teacher, they can all impart knowledge around hauora. It’s not that the health teacher knows everything, when you put it into Te Ao Māori. I think that’s what engages our rumaki students – they’re familiar with that comprehensive context.

Students in the rumaki were interested and engaged in sexuality education. The teacher spoke about the importance of establishing a welcoming and safe environment for students to talk about sexuality education issues in a comfortable way. This was underpinned by the strong relationships already established in the rumaki and the teacher’s use of humour to help students ease into what could potentially be somewhat awkward conversations. When you sit down with our kids… it’s a serious topic but you can laugh about it too. That makes them more open to talk. The kids really engage with it – they understand they’re in a safe place to talk.

Ministry of Education Sexuality Education guidelines

For more on effective and empowering approaches to sexuality education for Māori students, see p. 24 of the guidelines as a starting point

Outcome indicators

- Students who are Māori enjoy education success as Māori

- Students are confident in their identity, language and culture

02. Drawing on student voice

This story shows how inviting genuine student input into the development of the sexuality education programme leads to more relevant and responsive learning for students.

Most things in this school, including learning, start with something raised by students. The school has always listened to student voice, but in recent years they have strengthened this, making sure there are structures in place to ensure students had a voice in what affected them.

After media reported recent incidents (not involving this school), students approached leaders, concerned that consent was being taught too late. Senior health students thought the junior health programme was not strong enough, and did not meet students’ needs. They saw that the media portrayed unhealthy stereotypes, and students needed explicit teaching around how to recognise an unhealthy relationship. They said:

It’s such a big thing. I don’t know why they don’t cover it.

Senior students said sexuality education in Years 9 and 10 was heteronormative, focused too heavily on the physical aspects of sexuality education, and missed the deeper issues they needed to address.

We did a lot on sex education, not so much on sexuality education.

Senior student

They thought junior health should be about being accepting and open minded, and give students skills for getting along with people, not just focused on their own body. Senior students also thought there needed to be a stronger focus on consent, and healthy and unhealthy relationships and were concerned that the strong focus on puberty in Years 9 and 10 was not engaging, and may have put students off taking health as a senior subject. They wanted students to see that health education can give life skills, as well as opportunities to understand others and develop critical thinking.

School leaders and the board of trustees took the students’ concerns seriously, and encouraged them to work with health teachers to redesign the junior health programme. Health teachers were receptive of students’ feedback and concerns. They consulted students, and considered what they knew about their students and had seen in the media. The teachers recognised there was wide variety in the knowledge students had when they started in Year 9. They also identified that much of what the junior students knew had been learnt from their peers, and was not always accurate.

Teachers have a strong focus on knowing the needs of each student, including the students with additional learning needs learning in mainstream health classes. They know these students’ needs were as individual and diverse as other students’, and they have to respond in the best way for each student. For some students with additional learning needs this means sexuality education is best addressed through their Individual Education Plan, rather than with a larger group. Some students with additional learning needs are also supported to participate in the school’s support group for gender- and sexuality-diverse students.

Health teachers now ask Year 9 and 10 students how they feel about sexuality education, survey them about how health is meeting their needs, and work to break down the heteronormativity of the programme. They explore deeper issues, such as consent and relationships. Senior health students and the health teachers collaborated to redesign the junior health programme; each bringing their knowledge, interests and concerns so they could create a programme that would fit the needs of students.

Both teachers and students thought pornography should be addressed in greater depth. Teachers noticed students in Year 9 were asking questions about pornography, and so started to consider how they could strengthen this in their programme.

Senior students told ERO they thought that:

No-one knows what’s healthy and unhealthy, and they don’t really teach us.

They thought it was important that students be taught about pornography, to help them separate fantasy from reality, and distinguish between healthy and unhealthy relationships.

The board supports this as part of their belief that they needed to make sure every student’s needs were met. They recognised it was something many parents would want to speak to their children about, however this was not the case for all. They were concerned that if we don’t provide it at school, some students won’t get it at home.

Teachers and students were pleased with the process and the outcome of redesigning the junior health programme. A senior student praised the responsiveness of the teachers, saying a lot has changed in the five years I’ve been here.

Ministry of Education Sexuality Education guidelines

For a sense of the breadth of topics that should be covered at secondary school, see p. 23 of the guidelines as a starting point

Whole school review of the sexuality education programme should be heavily informed by student voice and identified student needs, see pp. 28-29 of the guidelines

Outcome indicators

- Students determine and participate in coherent education pathways

- Students establish and maintain positive relationships, respect others’ needs and show empathy

03 Learning how to support inclusion

This story shows how leaders and teachers can educate themselves in order to understand and improve inclusion for gender-diverse students.

Senior leaders at this school have been accepting of students for who they were, and warmly welcomed all students. They had not realised they needed to make the acceptance and welcome explicit for gender- and sexuality-diverse students to feel comfortable. Students’ questioning and challenging led teachers and leaders to greater knowledge and awareness. The deputy principal said:

I thought we were an accepting school, but I realised we need to make that more explicit so sexuality and gender-diverse students and staff felt welcome.

The principal realised the culture of explicit awareness had to come from the top, and made a point of being clear about this in public, such as school assemblies. The deputy principal wanted to continue improving, making the school more welcoming for gender- and sexuality-diverse students. The school had been working with various agencies to support individual students, but knew they could become more inclusive as a whole school.

The deputy principal worked with the mother of a former student to set up a panel of gender- and sexuality-diverse adults from the community to talk to staff. All school staff were included in the session. The panel told stories of their own experiences at school, and what could have been different to make their time at school better. Staff were interested and engaged, asking many questions.

The panel also helped develop a survey for students, and advised the deputy principal about other ways to support students, such as asking students how to keep them safe from harassment. The deputy principal said that seeking to improve and become more inclusive has become part of who we are.

The deputy principal and health teachers attended a course on the Sexuality Education guidelines. They thought it was important that all school staff were on the same page, so invited the course facilitator to present on diversity to all staff. Staff became aware they should look for reasons behind issues. By digging deeper, they found there were things they could do to make life easier for students. For example, they discovered some students who were persistently late to physical education had difficulty finding somewhere they felt safe and comfortable to change. They could create a space for these students to get changed, so they were on time.

The school began to consider other changes needed. To make gender-diverse students feel safe and enable them to fully access the curriculum, they had to consider toilets, the sick bay, and accommodation on school camps and trips. They had to be careful to manage the students’ safety, for example, by considering what name and pronoun they wanted used at public events, or leaving a classroom unlocked so the students had a safe place to go if needed.

The school encountered other barriers to being inclusive. Student management systems did not have a way to change a student’s name or gender. As of 2018, the student management system KAMAR has been updated to include diverse gender options, but would not update successfully to the Ministry of Education’s ENROL system with the new options selected. It was difficult to find gender- neutral resources for health education. They plan to continue working towards greater inclusivity. They recognise there will be a variety of practical challenges, as they realise that for both the school and wider education system some of this is new territory.

Ministry of Education Sexuality Education guidelines

Teachers may need professional development or other support to effectively deliver the sexuality education programme, see p. 26 of the guidelines

Outcome indicators

- Students enjoy a sense of belonging and connection to school

- Students feel included, cared for, and safe and secure

04 Building trusting classroom environments

This story describes the actions teachers and leaders undertook to create a safe and supportive environment in which students are able to have the open and honest conversations necessary for effective sexuality education to take place.

Respect between all is very important at this large single-sex secondary school, and is modelled from the top. Students told ERO the principal was genuinely open and interested in everyone’s ideas, and would respectfully consider their views and opinions. Part of how she showed respect was by following up and feeding back to the students once a decision was made.

School values and the example set by the principal set the expectations for staff behaviour. A board member told ERO teachers are all facing the same direction under [the principal’s] leadership. Leaders and teachers work together to make the school a safe place for students to be themselves and explore who they are.

One way they do this is by teaching students to critique opinions, rather than criticise people. They encourage students to express different opinions, so long as they are respectful of other views. They teach that agreeing to disagree is an acceptable option, and a way of honouring where everyone is at in their own journey towards understanding. Teachers explain that:

Everyone’s identity is important and we’re all in this together.

Before learning about relationships with others, students explored who they were as individuals. They learnt the importance of being comfortable with who they were, so they could make space for others to be themselves too. This supported the students to be understanding of others, and to reflect on how individual behaviour impacted on the class.

Older students told ERO how Year 9 students often found sexuality education awkward and strange, and would laugh as a defence mechanism in response.

They explained that not everyone’s expected to be the same level of maturity, but thought it was still important to teach sexuality education in spite of some students’ awkwardness, as it meant that students would be less awkward when the topic was taught in later years.

Other students told ERO how the relationships in their Year 9 class made it difficult to be open and have good discussions in sexuality education.

A student said:

People always feel a bit nervous. Some are really confident, others feel quiet. Teachers want everyone to know, learn and have an opinion.

This encouragement from teachers meant that by Year 10, students have learnt to trust each other. They are able to be more open with each other, and everyone in the class is able to contribute to discussions and activities. Students recognised the importance of having these trusting relationships.

Teachers have to know our class is ready. If we’re not, we won’t learn.

Students told ERO how their relationship with their teachers was also important for making them feel comfortable to ask questions. They said teachers needed to be warm, personable and knowledgeable, and that some teachers were more approachable than others.

To support students to have an adult to talk to, leaders make sure there was time for all students to visit the Hauora Centre and meet the support team of guidance counsellors and social worker. Adults in the school work together to provide wraparound care from whoever is the best fit for the student, as they know the importance of trusting relationships.

Ministry of Education Sexuality Education guidelines

For more information on effective programmes and pedagogies, see p. 25 of the guidelines

Outcome indicators

- Students show a clear sense of self in relation to cultural, local, national and global contexts

- Students set personal goals and self-evaluate against required performance levels

05 Balancing tradition and inclusion

This story shows how one school has managed diverse views and traditional beliefs by maintaining a focus on student wellbeing and inclusion.

This is a medium-sized state integrated co- educational secondary school in a main urban area. Leaders see themselves as walking a tightrope reconciling traditional church teachings with the reality of current society. When necessary, they point to the church’s teachings on acceptance and love for all people. Sexuality is seen as an aspect of hauora. The school has strong relationships with the Catholic community, including priests. They are supportive of school leaders’ stance on sexuality education and supporting gender- and sexuality- diverse students.

I needed to know that there was a growing awareness of the change in acceptance within the church.

The board’s policies and procedures demonstrated a Catholic perspective and promoted an inclusive environment where all students were safe. For example, the Pastoral Care Policy stated one of its purposes was to nurture and foster growth in the gospel values of reconciliation, respect, care and concerns for all persons.

We need to take our learning from the time we’re in and move forward with respect for the past.

A board member saw the school as a non- judgmental accepting community that valued the individual. One way they demonstrated this was their responsiveness to student voice. For example, a transgender student was supported to have their name changed on the school roll. Senior students, including a student leader, were open about their sexuality and said bullying was not an issue at the school.

The board set clear expectations for the teaching of sexuality education in a Catholic curriculum. The director of religious studies and the head of health and physical education both reported regularly to the board on the delivery of sexuality education.

The student council requested private changing facilities, as some students did not feel comfortable changing in front of others. The board provided these facilities, and was considering how they could also provide gender-neutral toilets.

The school consulted regularly with their parent community through a variety of ways, such as whānau hui, Pacific fono, surveys and other parent meetings. The school kept parents informed about opportunities in the community to strengthen their knowledge to better support their children, such as a seminar on pornography. They shared information about upcoming topics in sexuality education through newsletters. This information explained what would be covered, why it was important, and how it would be taught. The school found doing this meant it was rare for a parent to withdraw their child from sexuality education.

Students were consulted about the health programme and their wellbeing at school.

Students were invited to ask questions about sexuality education, and teachers were honest with them if the teacher did not know the answer and had to find out. Student surveys showed students ranked sexuality education highly. Board members rang each student new to the school to get feedback on how they were doing during their first year at the school.

The director of religious studies had the overall responsibility for sexuality education, which was mainly taught through religious education, with some parts being taught through health and physical education. Teachers worked together to coordinate the coverage, with input from the guidance counsellor, public health nurse and Family Planning.

They wanted to make sure their curriculum was comprehensive and responsive to the needs of their students, while ensuring they kept to the values of the Catholic Church.

The teacher responsible for the Years 7-10 programme referred to it as an ongoing draft, as they continually revised the programme based on what was wanted and needed by their students, what was appropriate, and what they saw to work best.

Teachers used a variety of resources and a wide mix of teaching strategies, including role play, choosing what was appropriate to the students’ needs and the school’s approach to sexuality. Students had the opportunity to submit questions anonymously that were then covered during the course of the unit. Teachers encouraged students to debate and explore different attitudes and values.

While health was not a subject option for Years 11 to 13, senior students covered aspects of sexuality education in external programmes, religious education, and other subjects.

Students told ERO their school was “good about sexual difference”, and felt they had had good opportunities to cover sex, consent, and alcohol and drugs as they relate to sex. However, while they appreciated the school’s efforts to meet their needs, some students told ERO that comprehensive sexuality education was “too late for some”, and the school focused too heavily on “the Bible view rather than what teenagers want to know”.

Students spoke to the counsellor about wanting to start a support group for gender and sexuality diverse students. While the group was able to meet and was supported by the school and priests, they wanted official recognition in the school. The school respected the students’ wishes, and was in the process of working with the board and school community to do this in a way that respected all views, in keeping with the school values. Students appreciated the approach, and the way the school made space for all students, recognising and valuing who they were. One student particularly appreciated the explicit acceptance, saying I needed to know that there was a growing awareness of the change in acceptance within the church.

Ministry of Education Sexuality Education guidelines

Consulting with communities is crucial to ensuring that the sexuality education programme is responsive. For further guidance on consultation, see pp. 34-38 of the guidelines.

It is important that senior students have ongoing opportunities to engage with sexuality education, even if they’re not taking NCEA Health. See p. 26 of the guidelines.

Outcome indicators

- Students value diversity and difference: cultural, linguistic, gender, special needs and abilities

- Students understand, participate and contribute to cultural, local, national and global communities

06 Sexuality education in Years 7 and 8

This story highlights how schools can design age-appropriate sexuality education programmes that provide the foundation for later learning.

This is a medium sized co-educational secondary school in a main urban area. Leaders and teachers at this school share an overall vision for student wellbeing. They believe their school culture flows from the staff, and they deliberately teach the culture to younger students. They see relationships as a necessary foundation for learning. The Deputy Principal told ERO:

If we don’t get wellbeing right, we can’t get the learning.

The school teaches three models of wellbeing relevant to their students: Te Whare Tapa Whā; Fonofale; and an American model familiar to their Filipino students. They teach students to notice each other’s wellbeing needs, and to support each other. Leaders monitor how well they met their students’ wellbeing needs through regular surveys.

Sexuality education is structured so students learn slightly ahead of when they will need the knowledge. Students appreciated this, as it meant they ‘wouldn’t panic’. In Years 7 and 8, sexuality education is integrated into other parts of their learning, delivered by the class teachers. In Years 9 and 10, sexuality education is mainly in delivered in health, by specialist health teachers. Students also have the option to take health as an NCEA subject from Year 11 onwards. The specialist health teachers work with the teachers in the Learning Support Centre (for students working within Level 1 of the NZC) to develop social stories and programmes appropriate to their learners.

At the start of each ‘kete’ the integrated units for Years 7 and 8 students, teachers find out what students already know. They do not want to repeat too much, but deliberately go over some content multiple times, as they recognised students were at different levels of maturity, and may not have picked up everything they needed to know the first time.

Students in Years 7 and 8 spend three to four hours per week, for six or seven weeks, on each kete.

Each year starts with wellbeing and relationships, then other kete follow. Kete topics include hauora, which has a specific focus on sexuality. In the hauora kete, students conduct an inquiry into a topic that interests them, set themselves a goal, and measure their progress towards that goal. Other kete, such as advertising, also look at topics related to sexuality education, such as using sex to sell.