Summary

This resource can be used with the School Evaluation Indicators. It brings together findings from ERO’s recent national reports to outline what works to accelerate progress for Māori students at-risk of underachieving in primary schools. We share approaches schools have taken where progress was accelerated and schools were able to extend their practices to help more students succeed. Innovative schools focus on inequity within their student population, resulting in improved outcomes for Māori students.

Whole article:

Accelerating student achievement: a resource for schoolsIntroduction

Accelerated improvement requires a whole system to function as a collaborative learning community that is advancing progress on the four areas of leverage: pedagogy, educationally powerful connections, professional learning and leadership.

(Adrienne Alton-Lee, cited in Mathematics in Years 4 to 8: Developing a Responsive Curriculum; ERO, 2013)

Equity and excellence

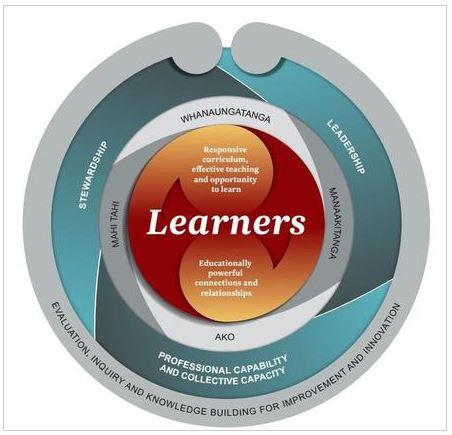

This image is a circle with learners at the centre. Surround this is are two koru shaped rings the top one is responsive curriculum effective teaching and opportunity to learn. The bottom one is Educationally powerful connections and relationships. The next ring is Whanaugatanaga, Manaakitanga, AKO and Mahi Tahi. The next ring is Leadership, Proffessional capability and collective capacity and Stewardship. The last ring ends a the top with to koru shapes it reads, Evalualtion inquiry and knowledge building for improvement and innovation.

The School Evaluation Indicators (ERO, 2015) position the learner at the centre. The growth and development of the learner is carefully nurtured by those around them. The focus on what matters most in improving valued student outcomes.

The indicators foreground the Māori concepts of manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, ako and mahi tahi. Together these frame how we approach education provision in the New Zealand context, challenging us to recognise and respond to the educationally limiting effects of deficit theorising about students and their potential.

What ERO knows about accelerating achievement for Māori students

This resource can be used with the indicators. It brings together findings from ERO’s recent national reports to outline what works to accelerate progress for Māori students at-risk of underachieving in primary schools. We share approaches schools have taken where progress was accelerated and schools were able to extend their practices to help more students succeed. Innovative schools focus on inequity within their student population, resulting in improved outcomes for Māori students.

Raising achievement in primary schools

This June 2014 ERO report explores the deliberate actions leaders and teachers took that increased the number of students achieving ‘at’ or ‘above’ the national standards. The actions provide a way forward for improving the progress of Māori students achieving below the standards for their year level.

What did effective schools do?

Leaders and teachers at effective schools responded innovatively to underachievement and successfully accelerated progress for the students involved. They:

- designed and implemented an improvement plan that enabled more students to achieve better results with less inequity across the school population.

- usually undertook additional assessments with students needing to accelerate progress to better understand their strengths and needs

- were strategic and successful in their actions to accelerate progress.

- strategically trialled a new approach in one area and expanded the trial by increasing the number of students and teachers involved in the new approach.

- trialled well-researched strategies rather than continuing with what was obviously not making a difference.

- focused on building relationships with students, their parents and whānau. Some also extended their partnership to hapu and iwi

What is accelerated progress?

The purpose of accelerated progress is to enable the learner to achieve at the national standard for their year level. Achievement can be considered to be accelerated when a student makes more than ones year’s progress over a year on a trajectory that indicates they will achieve at or above the standards by the end of Year 8 or sooner.

Māori enjoying success as Māori

Improvements in achievement resulted when schools:

- integrated elements of students’ identity language and culture into teaching and learning

- used their student achievement data to target resources for optimal effect

- provided early intensive support for those students at risk of falling behind, created productive partnerships with parents, whānau, hapu, iwi, communities and business focused on educational success, retained high expectations of students to succeed in education as Māori.

What does strategic and successful look like?

Strategic and successful schools had both a long-term commitment to acceleration and a planned approach to improvement that provided wrap-around support for students and teachers. For example when data identified that a group of Year 8 boys were not achieving well in writing the school provided a remedial Year 8 writing programme. At the same time they aimed to ensure this achievement pattern didn’t reoccur by providing professional development in writing for teachers of Year 4 to 8 classes.

Capabilities that made the difference in a school’s ability to accelerate progress

- Leadership capability - school leaders were able to design and implement a coherent whole school plan that focused on targeted support for students and teachers for equitable outcomes.

- Teachers’ capability - teachers were able to find and trial responses to individual student strengths and needs that engaged and supported students to accelerate their progress in reading, writing and mathematics.

- Assessment and evaluative capability – leaders and teachers could understand and use data, and know what works, when and why for different students.

- Capability to develop relationships with students, parents, whānau, trustees, school leaders and other teaching professionals to support accelerated progress.

- Capability to design and implement a school curriculum that engaged students.

Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau

ERO’s November 2015 report shares the ways schools parents, families and whānau successfully worked together to support students who needed to accelerate their progress.

Educationally powerful connections involved two-way collaborative working relationships that reflected the concept of mahi tahi – working together towards the specific goal of supporting a young person’s success. The best examples were learning-centred collaborations between students, their teachers and their parents and whānau that focused on the student’s learning and progress.

A whānau-like context was established in which parents, teachers and students all understood their rights and responsibilities, commitments and obligations – whanaungatanga – to help the students succeed.

The intent of the relationship with parents was to extend learning across the home and school. Teacher and leaders that understood this intent:

- listened to what whānau knew about their child’s interest and what worked for them

- involved parents in setting goals and agreeing on next learning steps

- developed a share language about learning and achievement with students and their parents and whānau

- valued students wellbeing and were genuinely interested in them and their whānau

As a result students’ progress accelerated.

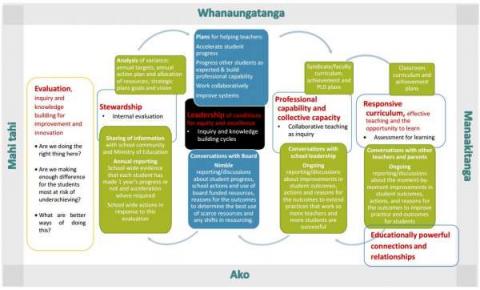

When school leaders designed initiatives that focused on particular students that needed to accelerate their progress, teachers systematically strengthened their working relationships with these students’ parents and whānau. Leaders used an inquiry framework below to help teachers:

- make time for frequent and regular conversations with parents and whānau to learn more about who each student is in the wider context of school and home, in order to develop holistic and authentic learning goals and contexts

- extend learning by designing and putting in place multiple and aligned learning opportunities where students could learn at school and at home

- evaluate how well these learning opportunities support parents and whānau and are aligned between home and school

- be persistent and keep using what worked, change and improve what did not work, and transfer what worked to support other students and their parents and whānau.

Inquiry framework

this image is the framework for inquiry which five circles forming a large circle joined by a arrow linking all circles together. Outside of this are four boxes in each corner. At the centre it reads: School has evidence of impact. Students have been deliberately supported to inprove outcomes. The five circles read from top clockwise: Identification of students at risk of underachieving, Identifying learning strengths and needs language identity and culture, intrests and aspirations, Respond wiht deliberate actions and innovations to improve student outcomes, Recognise the impact of the actions that influenced the improved student outcomes and Refocus on next actions. The boxes in the four corners read from top right clockwise: 1 - to know who the student is in the wider context of school and home in order to develop holistic and authentic learning goals. 2 - to extend learning by designing and implementing multiple aligned learning opportunities. 3 - to evaluate the multiple aligned opportunities to know what worked for whom, when and why. 4 - To be persistent and: sustain what worked about the relationships for the students involved, change and improve what did not work, transfer what worked to more students and their parents, families and whanau.

Raising student achievement through targeted action

This December 2015 ERO report explains how schools that successfully raised achievement had a clear “line of sight" to the students most at risk of underachieving. When setting targets leaders made certain that people at all levels of the school understood who the students were they were focusing on and what their role was to bring about the necessary improvement.

Framing disparities for action: Leaders designed, resourced and implemented a focus on improving both student outcomes and school capacity for equitable outcomes.

Some of the characteristics of the schools where targets and the related actions accelerated students’ progress:

Leaders ensured:

- goals and targets set an optimum level of challenge for teachers and students, by being achievable but high enough to make a real difference

- framed analysis of disparities in positive ways to focus everyone on equity, priorities and expectations

- there was alignment between the school’s visions and values and the deliberate actions taken

All teaching staff:

- knew what one year’s progress looked like

- were involved in the process of identifying students needing support, deciding on the most appropriate support, and monitoring outcomes of their actions.

- had a ‘case management’ approach to supporting students needing to accelerate progress.

- regularly explored the effectiveness of their responses then designed and evaluated follow-up actions.

Students:

- knew they were a target student

- were supported to understand the performance required for each curriculum level

- set personal goals and self-monitored progress

Their goals and progress were shared with parents and whānau.

Students as partners in learning

Schools that were more likely to see a great improvement in student outcomes included students as active partners in designing the plan to accelerate their progress. Raising Achievement in Primary Schools (ERO, 2014) discussed how this partnership with students gained their commitment to the plan’s success.

By including students as partners, teachers were able to include learning contexts that were based on student interests. Learning could happen in the ways students preferred, such as collaborative group tasks, oral work, and self and peer assessment. Students gave feedback to their teachers around what worked or did not work.

Student-centred literacy and mathematics progressions supported students to describe what they had learnt, what they needed to learn, and how they learnt. Students were able to use these progressions with examples of their work to explain their progress and achievement to their parents and teachers.

The Collection and Use of Assessment Information in Schools (ERO, 2007) explained how schools were most effective when students were given constructive reporting of their achievement. This meant that students were able to have useful conversations with parents and teachers about how they were doing and strategies for how they could improve.

Raising Student Achievement Through Targeted Action (ERO, 2015) gives an example of a school using specific strategies to raise achievement in writing for Māori students. Teachers used achievement data to evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching, and identified where improvement was needed the most.

Teachers worked with local iwi to develop authentic mātauranga Māori experiences, designed to provide contexts for reading and writing. They also attended professional development sessions aimed at helping students to develop their comprehension, vocabulary and fluency skills.

Teachers learnt the importance of having a learning-centred relationship with whānau to support their students to succeed.

Wellbeing for Children’s Success at Primary School (ERO, 2015) outlines how students’ wellbeing and achievement are interrelated and interdependent. A student’s sense of achievement and success is enhanced when they feel safe and secure at school. This in turn affects their confidence to try new things and their resilience to persevere with new challenges.

In schools with an extensive approach to wellbeing students contributed to many daily decisions, such as what and how they learnt, who they interacted with and how they engaged. Students were expected to develop and use skills in leadership. They were seen as inherently capable, despite any barriers or challenges they faced. Students were in control of many of their school experiences.

Teachers provided opportunities for students to be aware of, and respond to, their own learning strengths and needs. The use of:

- assessment practices to improve learning ensured students had clarity about their personal learning, that is, they knew what they were learning and why, how they were going, and how they could improve

- inquiry-based learning ensured students had a voice in what was important to learn and how – that is, the classroom curriculum was based on student strengths, needs and interests

- studying local, social and environmental issues ensured students had opportunities to make change and develop clarity around personal values and respect for others.

Reading and writing in Years 1 and 2

This 2009 ERO report highlights that the expectations of both school leaders and teachers can influence the rates of children’s progress or actual success. Even when teachers are focused on children’s learning, inappropriate teacher expectations can undermine them, or impede progress. Teacher expectations have been found to vary according to student ethnicity, ability, gender and other characteristics unrelated to a student’s actual capability.

One critical element for success is that teachers’ expectations focus on a child’s potential rather than current or past performance. Reading and Writing in Years 1 and 2 discusses expectations in schools with good practice.

Students learn in an inclusive environment where they are respected as individuals and where teachers hold high expectations for their achievement and progress. Teachers show respect for and understanding of their students’ background. An example of appropriate expectations is from Partners in Learning: Good Practice.

Student voice

In many schools teachers and leaders discussed collecting student (and parent) voice. They had not explored what they meant by this or how they intended to promote and respond to it. Student voice can mean different things.

Most schools used a survey to hear students’ views. However, if the purpose was to increase students’ self awareness about their views, competencies and knowledge, classroom discussions can enable teachers to respond with learning opportunities that build on these strengths. Teachers in schools that had an extensive approach to wellbeing, tended to use assessment practices to improve learning and to support inquiry-based learning.

If the purpose was to have teams of students in a leadership role contribute to the design of learning experiences that affect their wellbeing, teachers and leaders needed to provide the time and space for this.

Māori parents’ perspectives

ERO reported on Māori parents’ and whānau perspectives in Partners in Learning: Parents’ Voices (ERO, 2008). Parents and whānau told ERO that their children and mokopuna were their priority. They felt that their involvement in their children’s education was critical.

These Māori parents wanted:

- They wanted to be involved in their child’s school and invited to be part of their child’s learning.

- their children to be confident learners who accepted challenges and maintained their personal mana

- their culture and values acknowledged through Māori protocols (e.g. mihi and karakia at meeting)

- schools to provide programmes in te reo Māori and tikanga

- teachers to have a range of skills and strategies to engage their children in learning

Achievement expectations

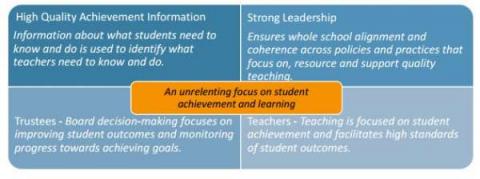

This images shows four boxes and a central box in the centre overlapping all four boxes. The central box is An unrelenting focus on student achievement and learning. The first box from top left clockwise reads: High Quality Achievement Information, Information about what students need to know and do is used to identify what teachers need to know and do. The second box reads: Strong Leadership, Ensuures whole school alignment and choherence across policies and practices that focus on resource and support quality teaching. The third box reads: Teachers, teaching is focused on student achievement and facilitates high standards of student outcomes. The fourth box reads: Trustees, Board decision-making focuses on improving student outcomes and monitoring progress towards achieving goals.

Board responsibility and resourcing

Boards play a vital role in schools that effectively accelerate progress for students.

- Boards received good quality information regularly from school leaders, and were active and engaged – independently questioning the data and seeking to further their own understanding.

- They used the data to inform resourcing decisions, which were targeted and responsive to areas of need.

- Boards also used the information to set appropriate targets to raise achievement and align them with strategic goals.

They use the information they receive to make decisions about funding to resource additional professional development for teachers, targeted programmes, extra staff, and release time. They then receive robust information about how those resources helped students that need to make the most progress.

Trustees in the most effective schools make thoughtful decisions based on a range of telling evidence. These schools gather data using both quantitative (numerical) and qualitative (narrative) methods. The data is scrutinised carefully for what is and isn’t obvious. Further data is asked for and gathered if necessary to provide a more detailed picture. Data analysis includes establishing what is significant, what is working well and what isn’t, how groups or cohorts compare, what patterns or trends are showing up, and whether improvement or progress is apparent. The findings are integrated into board decision-making processes which include prioritising, evaluating possible interventions or programmes, action planning and deciding on success criteria. Examples can be found in Schools’ Use of Operational Funding: Case Studies (ERO, 2007):

Conclusion

In conclusion: When putting all the findings together we know these things are happening in schools that are accelerating Māori students’ progress:

- Leaders and teacher know the names, needs, strengths and interests of the children that need to make the most progress

- Leaders and teacher set high expectation for every child’s achievement

- There is a sense of urgency to support students to accelerate progress

- The student, parents and whānau are involved in setting the goals and contributing to and monitoring the improvements

- Teachers and leaders know what one year’s progress looked like and were aiming to have target students progress more than a year in a year

- Leader, trustees or teachers are able to explain the reason for the gains in achievement and how to sustain the progress

- Students know what they have to do to make progress and when they have succeeded

- Teachers are able to describe the progress within the range of students focused on; who had made the most progress and those they are still concerned about

- Teachers try new approaches and use data to establish what works and for whom it works -they discard things that aren’t working

- Teachers use contexts for learning that build on the child’s strengths and match the child’s interest

- Ongoing reporting to the board, student and whānau is honest as it describes successes as well as no progress or declines

- Trustees are able to make informed decisions about what resources to fund and then can see the impact of the additional funding

- Both short-term and long-term responses are in place to provide support for the students who are not achieving and to improve teaching practice to reduce the numbers of students needing support.

There is a ‘line of sight’ from the board to the student who needs to accelerate their progress. Everyone from the trustees, whānau, leader, teacher, and the student know what they are focusing on and what their role is in making the necessary progress.